Thanks for reading this year, folks. It’s a great pleasure indulging my curiosity here, and to have had more than a few of you seem to enjoy it too. It’s much appreciated. Merry Christmas, and all the best for 2025.

Does the Church need science? Certainly not, the cross and the gospel are sufficient for her. But nothing human is alien to the Christian. How could the Church have failed to take an interest in the most noble of the strictly human occupations: the search for truth? – Georges Lemaître

*

In 1993, the magazine Sky & Telescope tried to correct what they thought to be a grave injustice: that the grandest of ideas had been tarred with a childish label – and, to make things worse, one coined by a man scornful of the theory it described.

For the editors of Sky & Telescope, the “Big Bang” – the description, not the theory – was intolerably infantile and, having been casually conjured by Sir Fred Hoyle, the astronomer who died in 2001 still sceptical of what had become cosmology’s prevailing origin theory, it was also “inappropriately bellicose”.

And so, the editors thought, it was time to liberate the very idea of the birth of space-time from both Hoyle’s scepticism and his belittling onomatopoeia.

To achieve this, they announced a public competition. The result was hilarious.

*

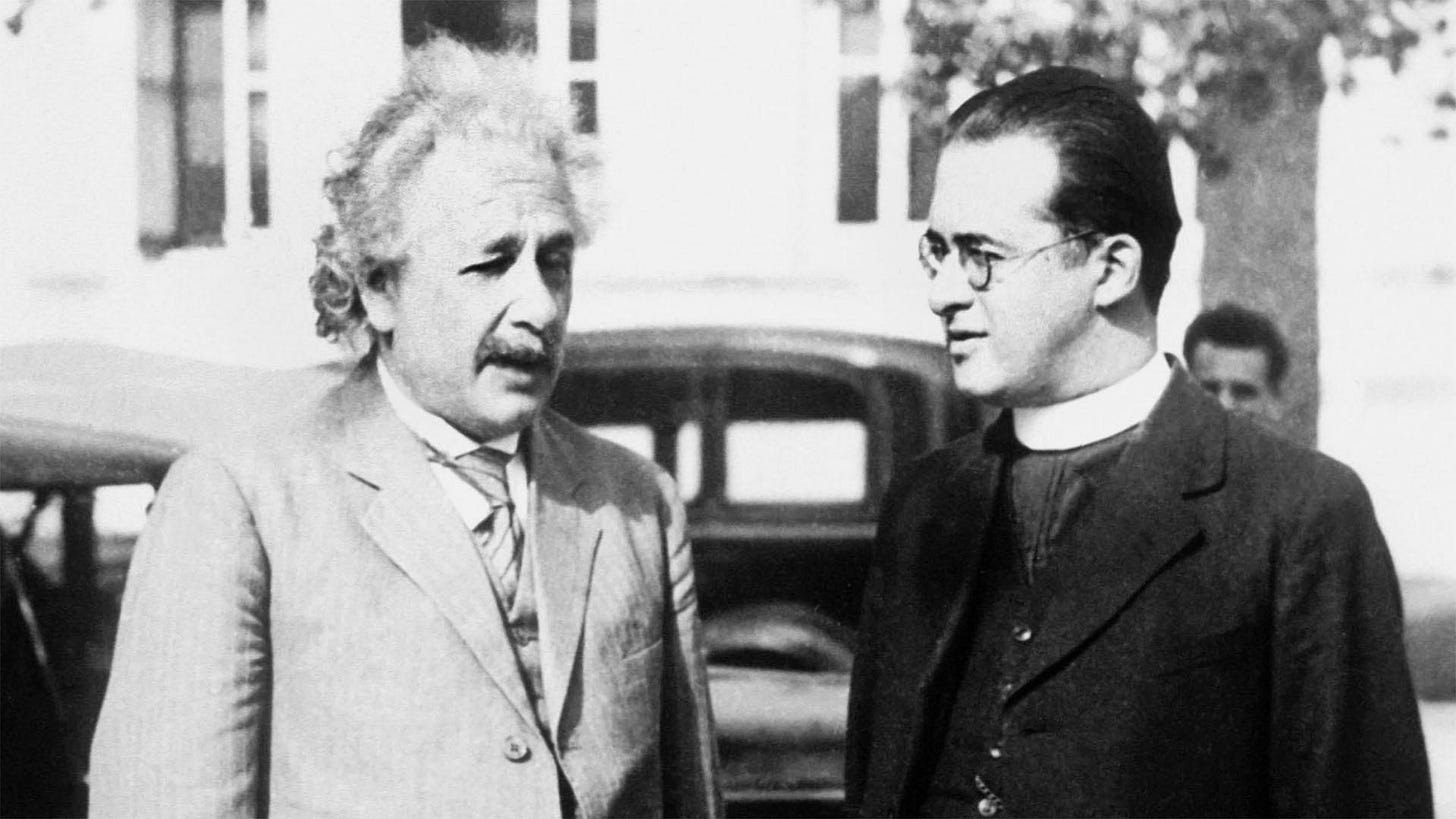

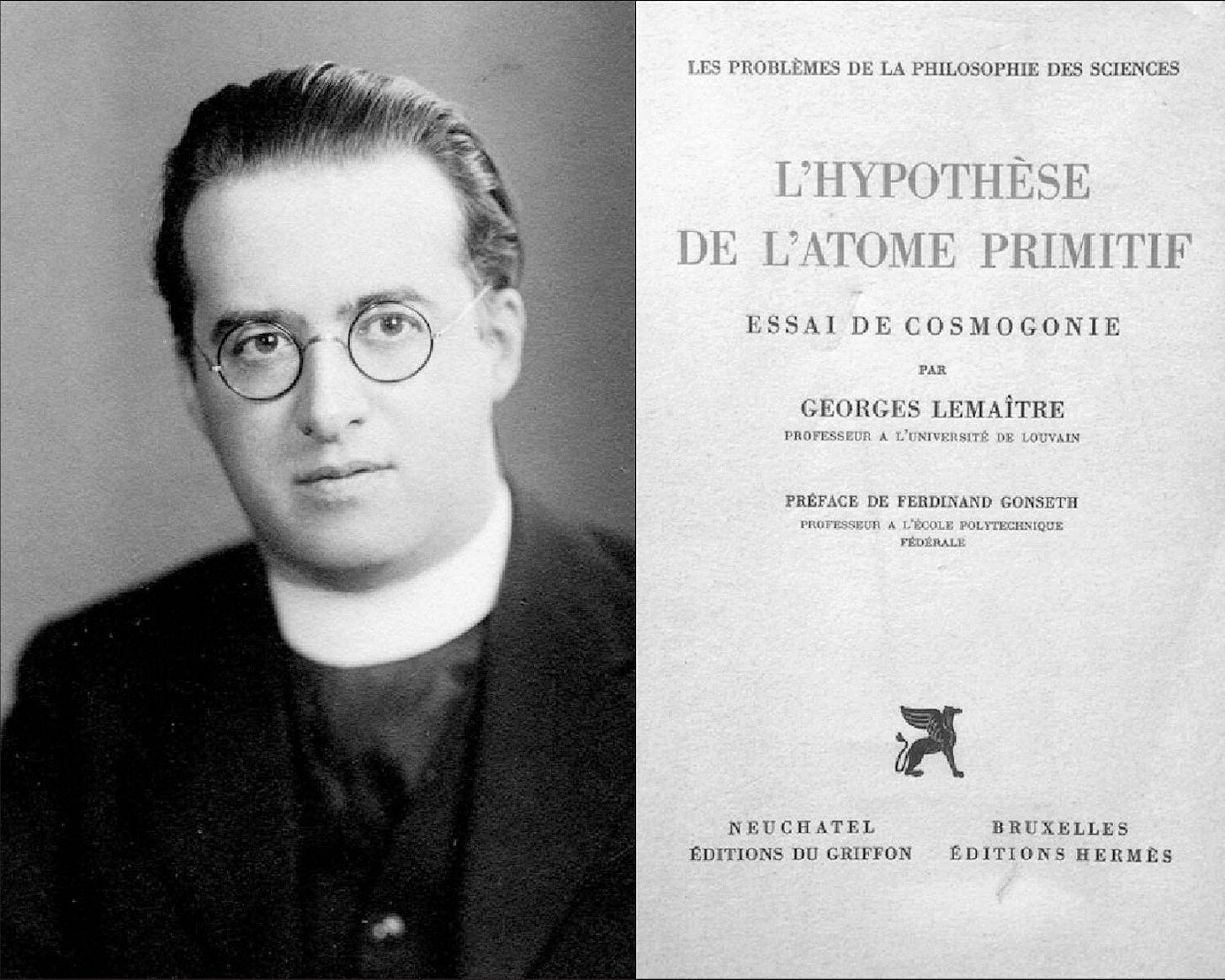

Georges Lemaître was born in 1894, a Belgian man who distinguished himself in the Great War before becoming both a Catholic priest and influential astrophysicist. Lemaître was one of the first to theorise that the universe had a beginning – that there was once a “day without yesterday”.

Scientific theorising doesn’t often work in vacuums, but instead borrows, reinterprets or defines itself in opposition to other work. Lemaître was no different. Einstein’s theory of relativity influenced him, as did the work of his Cambridge mentor, Sir Arthur Eddington.

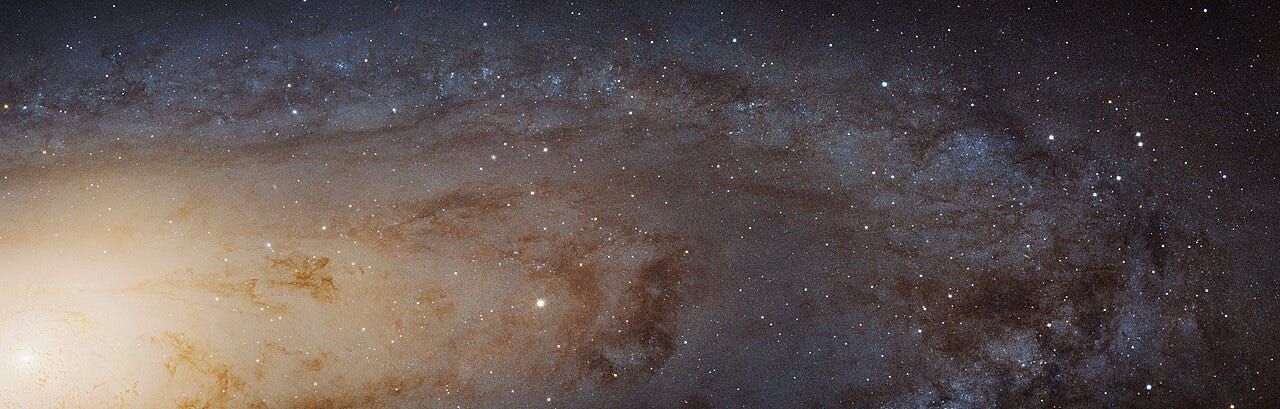

But it was Lemaître who first proposed, in 1927, that the recession of galaxies was proof of the expansion of the universe. Two years later, the published observations of Edwin Hubble confirmed this.

Lemaître’s theory of inflation came before his theory that the universe had a beginning. The Belgian worked backwards: if the universe was expanding, then at some point it must have been much smaller. In 1931, Lemaître arrived at the bones of the Big Bang theory: a “unique atom”, which he would later re-name the “primeval atom”.

This, he theorised, was a single and profoundly pregnant particle, a prototype of the universe, that became unstable, exploded, and spewed all matter that now comprise the universe. (To risk further bending your brain, and mine, Lemaître’s idea of a primeval atom differs from a modern theory of the Big Bang, which says that instead of a single, pregnant particle there was an initial singularity of zero volume but infinite density.)

Lemaître’s theory was largely ignored at the time. For one, unlike Hubble’s observational findings (most critically of the red-light spectrums we received from distant galaxies, which we could interpret as their receding from each other) Lemaître’s work was purely theoretical – a “clever jeu d’esprit” thought the British mathematician, Ernest W. Barnes.

Most alarming to physicists, though, were the theological implications of Lemaître’s theory. Aristotle had argued that matter was eternal, and that remained a popular view in Lemaître’s time as it pertained to cosmology: that the universe has always been; that it has no beginning and will have no end. There was no invention of time.

The idea that the universe could be dated – that there was a specific beginning – was anathema to many, including Einstein, who theorised a static (and eternal) universe in 1917, only to later accept its dynamism after the “redshift” observations of Hubble had irrefutably demonstrated its expansion.

For a layperson like myself, it seems the problem of infinite regression exists with either model – static or dynamic; eternal or temporally defined. But the idea of there being a beginning of the universe – and the resultant question of what went before, or how the super-pregnant particle came to exist – specifically troubled atheists with its implication of God.

Enter the British astronomer, Sir Fred Hoyle. He had proposed, and enjoyed support for, his “Steady State” model of the universe in 1948. There could be no universe, he said, without there being space and time for the universe to be created in. While Hoyle accepted the universe’s inflation, per Hubble’s observations, the universe was still eternal, he said, and that it remains in a constant state – despite its expansion – by its own modest creation of new matter to compensate for any loss in density.

By some measure, the “Steady State” theory was borne from hostility towards the idea that everything had once came from nothing (or close to nothing) – for one, it defied a fundamental law of physics: that energy conserves itself.

The hostility was also more personal. The idea that there was a defined birth of space-time chimed too well with the doctrine of Christian creation. And Hoyle was explicit about this. “The reason why scientists like the ‘Big Bang’ is because they are overshadowed by the Book of Genesis,” he said in his BBC lectures. “It is deep within the psyche of most scientists to believe in the first page of Genesis.”

I don’t believe this is true, but one could still read Lemaître’s first papers about the primeval atom and fairly transplant its ideas to Genesis. Allow me a creative desecration of its opening lines:

In the beginning God created the primeval atom.

And the universe was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of singularly dense cosmic matter.

And God said, ‘Let this particle spew light’: and there was light.

And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.

And time was born, and the seeds of life too.

Pope Pius XII thought similarly, and in a 1951 speech before the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, he said:

It is undeniable that when a mind enlightened and enriched with modern scientific knowledge weighs this problem calmly, it feels drawn to break through the circle of completely independent or autochthonous matter, whether uncreated or self-created, and to ascend to a creating Spirit. With the same clear and critical look with which it examines and passes judgment on facts, it perceives and recognizes the work of creative omnipotence, whose power, set in motion by the mighty “Fiat” pronounced billions of years ago by the Creating Spirit, spread out over the universe, calling into existence with a gesture of generous love matter bursting with energy. In fact, it would seem that present-day science, with one sweeping step back across millions of centuries, has succeeded in bearing witness to that primordial “Fiat lux” uttered at the moment when, along with matter, there burst forth from nothing a sea of light and radiation, while the particles of chemical elements split and formed into millions of galaxies.

Though he was never mentioned by name, Georges Lemaître wasn’t pleased with the Pope’s tacit endorsement. His displeasure, likely communicated through an intermediary, was expressed to the Vatican. Personally, Lemaître saw no contradiction between his faith and his scientific work, but he considered his theory nascent, untested and fragile. That the Pope might use the latest in cosmological theory as proof of God’s existence lay uneasily upon him.

Lemaître believed in Deus Absconditus, or a hidden God, and that while his “primeval atom” was likely His fruit – though this was something Lemaître never said – the laws of physics that followed the initial explosion remain constant, observable and autonomous. But on the theological implications of his theory, Lemaître remained modestly impartial:

“As far as I can see, such a theory remains entirely outside any metaphysical or religious question. It leaves the materialist free to deny any transcendental Being… For the believer, it removes any attempt at familiarity with God… It is consonant with Isaiah speaking of the hidden God, hidden even in the beginning of the universe.”

*

I’m going to get to the etymology of the “Big Bang”, I promise, as I’ll come to the competition to rename it. But before I do, there are still some things to mention: one, the sudden dissolution of the “Steady State” model of cosmology; and two, the lingering theological implications of the Big Bang.

For a long time, theories of cosmology were heavily theoretical. Mathematics, rather than observation, were their meat – we had not yet built telescopes sufficiently powerful to observe distant galaxies.

First, Edwin Hubble – using the world’s then-most powerful telescope at Mount Wilson, California, began observing the light spectrums received from distant galaxies, and thus found proof of cosmic inflation: “Evidence of this expansion comes from observing the spectrum of colours emitted by galaxies,” NASA explains. “As space expands, galaxies move farther away from each other, and their light elongates while becoming a redder colour. This phenomenon is called cosmological redshift.”

Then, in 1965, a major discovery was made which crippled the idea of an eternal universe in a “steady-state”. Twenty years before, it was theorised that, if the universe was born in a singular moment of grand, nuclear explosion, then space would be filled with a kind of fossilised radiation – microwaves that fill the universe as a relic of that initial bang.

And so it was. The universe was replete with “cosmic microwave background”. It has remained a pillar of Big Bang theory ever since.

Today, the age of the universe is given as 13.8 billion years. The question of what existed before that remains unanswerable. If matter is not eternal, and the universe has a definite beginning, then we return to the cosmology of the turtle and the problem of infinite regression.

It’s how Stephen Hawking opened A Brief History of Time:

“A well-known scientist (some say it was Bertrand Russell) once gave a public lecture on astronomy. He described how the earth orbits around the sun and how the sun, in turn, orbits around the center of a vast collection of stars called our galaxy. At the end of the lecture, a little old lady at the back of the room got up and said: ‘What you have told us is rubbish. The world is really a flat plate supported on the back of a giant tortoise.’ The scientist gave a superior smile before replying, ‘What is the tortoise standing on?’ ‘You’re very clever, young man, very clever,’ said the old lady. ‘But it’s turtles all the way down!’”

With respect to the great man, Hawking was attributing here to a specific man in a specific place a story – or fable – that had been told hundreds of times long before the example given.

Regardless, it stands: in the woman’s cosmology, the Earth is a flat disc and does not “fall down” because it’s supported upon the back of a turtle. But when asked what supports the turtle, she says: Well, it’s turtles all the way down.

If space-time has a beginning, then what existed before it? Well, we might say a “void” and leave it there, but that punctuation point will trouble the mind of anyone willing to sit with it.

And if there was merely a void, then how, precisely, did nothing conceive everything? If there was a hyper-dense particle, then where did that particle come from? Well, it’s pregnant particles all the way down.

*

In March 1949, in one of a series of public lectures given on BBC radio, Sir Fred Hoyle first used the term “Big Bang” to describe the rival school of cosmology, the one he described as proposing “that all the matter of the universe was created in one big bang at a particular time in the remote past’’.

A proposition, he said, that was “irrational”.

It’s true that Hoyle was sceptical of the theory, as it’s true that he was both brilliant, combative and inclined towards some rather fringe theories towards the end of his life (like his belief that the 1918 flu pandemic was introduced to Earth via cometary dust).

And it’s true that Hoyle, after the discovery of the Cosmic Microwave Background, didn’t surrender his theory, but rather creatively modified it to allow for the discovery – and stuck to his rejection of the Big Bang theory until his death, in 2001. In 1992, he described it as being like “medieval theology”.

But it was Hoyle’s public lectures, made when there was still competition between the two major cosmological theories, that introduced the term “Big Bang”. As the theories jostled, and the theory that it derisively described had not yet become prevailing, the term itself was barely used. Mentioned casually by Hoyle in 1949, decades would pass before the phrase became lingua franca.

But eventually it did. That simple phrase, casually coined by the theory’s most famous sceptic, would finally enter the zeitgeist. And so, almost 50 years after Hoyle’s lecture – and about 30 years after his steady state model seemed insupportable – Sky & Telescope magazine decided it was time to rename the grand theory of the birth of the universe.

*

So in 1993, the editors of Sky & Telescope announced their public competition to rename the “trivialising” “Big Bang”. All were welcome to submit, and while there would be no financial reward for the winner, success promised something greater: the unique distinction of re-naming the grandest theory of all.

The magazine’s editors would adjudicate, but with the help of astronomers and astrophysicists, including Carl Sagan. From 41 countries they received 13,099 entries which largely came from “non-scientists”. Entries arrived from school kids and prison inmates; from medics and college students. Entries like: “Jurassic Quark”, “MOM (Mother of Matter)” and “Portrait of the Universe as a Young Bam”.

Sadly, all of these were rejected. So too more serious and prosaic suggestions like “The Grand Expansion” and “The Super Seed”. Having read them all, one judge said: “This outpouring of creative, pedestrian, religious, ingenious, confused, profound, and insightful suggestions offers an unprecedented look at lay-peoples’ thinking about the origin of the universe.”

So what was the result of this creative outpouring? Well, the judges surrendered to the power of the term they had sought to overcome. Of the 13,099 entries none, they thought, could possibly better what had already been established.

The year before the competition, Sir Fred Hoyle had been asked about the stickiness of his phrase. “Words are like harpoons,” he said. “Once they go in, they are very hard to pull out.”

And so it was.