A version of this piece first appeared in The Saturday Paper.

It was September 6, the day after the massacre, and thousands of athletes and spectators were gathered in Munich’s Olympic Stadium for the memorial service. The night before, the hostage taking of half of Israel’s Olympic delegation by the Palestinian terror squad Black September had resolved in mass confusion and maximum blood on the tarmac of a military airport.

In the stadium, the world’s flags were at half-mast. The Israeli survivors sat up front. Various dignitaries spoke, before the final eulogist stood: the International Olympic Committee’s president, Avery Brundage. It was a curious speech, both admired and detested at the time, but of which history has not been kind.

Opening with an explicit condemnation of the slaughter, Brundage then began prosecuting jarringly irrelevant grievances: about African countries’ “naked political blackmail” in opposing the IOC’s decision to include Rhodesia in these Games; and then airing his long and fanatical commitment to maintaining the amateurism of the Olympics and his conviction that the commercialisation of sport was grossly impure.

Weird stuff, but remembered most of all was Brundage’s defiant assertion that the Games would continue. “We cannot allow a handful of terrorists to destroy this core of international cooperation and good will which the Olympic Games represent,” he said. “The Games must go on!”

And so they did. After the mourners left, groundskeepers began watering the stadium’s turf in preparation for competition. As they watered the grass, the charred corpses of the athletes remained in the wreckage of the helicopter into which one of their captors had thrown a grenade.

*

The 1972 Munich Olympics – “The Carefree Games” that would become known for mass murder – was heavy with historical ironies. And, extraordinarily, Avery Brundage would personally bridge the ’72 Games with the previous German Olympics: Hitler’s Berlin Games of ‘36.

Born in Detroit in 1887, Brundage had competed for the US in track and field at the 1912 Olympics. After that, he carved a very long and influential career as a sports administrator. Renowned for his rock-ribbed conservatism, fastidious personal regimes and scepticism of female athletes, in time Brundage’s commitment to amateurism would transform him into a notorious anachronism, the Olympics’ version of Hiroo Onoda – the Japanese lieutenant who refused to accept his country’s surrender in 1945, and continued guerrilla warfare in the Philippine jungles for another 30 years.

The purity of amateurism was “like a religion” to Brundage. Even if Soviet athletes benefited from state-run programs while still qualifying as amateurs, and thus enjoyed an advantage over self-funded athletes elsewhere, Brundage was unmoved: “There are only two kinds of competitors,” he once said. “Those free and independent individuals who are interested in sports for sport’s sake, and those in sports for financial reasons. Olympic glory is for amateurs.”

On this, he was an idealist. But the memorial seemed a strange time to remind folks of the point.

*

Prior to Hitler’s Games, Brundage had become president of the American Olympic Committee and a member of the IOC. Opposed to an American boycott of the 1936 Games, Brundage travelled to Germany to meet with Hitler’s Reich and seek assurances about the treatment of Jews that he might take home to mollify those who argued against America’s participation.

He did just that, satisfying himself that Hitler’s gang meant no harm and, anyway, “The politics of a nation is of no concern to the International Olympic Committee” and that “Non-participation would do more harm than good.”

In private, Brundage’s feelings were expressed more explicitly. In a 1936 letter to Sigfrid Edström, then the IOC’s vice-president, he wrote: “The New York newspapers which are largely controlled by Jews, devote a very considerable percentage of their news columns to the situation in Germany. The articles are 99% anti-Nazi.”

In 1972, West Germany was anxious to present itself as a gentle nation that had purged – but not forgotten – its evil history. They held a memorial at the remains of the Dachau camp, which had opened three years before the Berlin Games and lay just a few javelin-throws from the Munich stadium, and decided upon a conspicuously light security presence for the Olympics themselves, lest armed and uniformed men might remind the world of its past.

These were promoted as the “care free” games, even if the Israeli team and its government were concerned about their safety and the cheerful laxness of German security made them feel less-than-relaxed. After all, the year 1972 existed within an apogee of global terrorism and West Germany itself, in the months prior to the Games, had experienced several fatal bomb blasts committed by its own far-left Red Army Faction. Popularly known as the Baader-Meinhof Group, its leaders had been trained in Jordan by al-Fatah leader Abu Hassan Salameh – the man who designed the Munich operation – and their names would be included in the list of prisoners the group would demand released in exchange for their hostages.

And so, a little before 5.00am on September 5, while dressed in athletic tracksuits and carrying sports bags containing machine-guns and grenades, eight members of Black September scaled the modest and unguarded fence surrounding the athlete’s village. They did so with the help of a few drunk Canadian athletes who were attempting their own late entry after breaching curfew and who had mistaken the killers for peers.

*

The 1972 Games were the first Olympics to be broadcast live – and so, the hostage taking of the Israeli team was the first time a terrorist operation was broadcast live too. One estimate has the global audience for the siege at 900 million.

September 5, directed and co-written by the Swiss Tim Fehlbaum, tells the story of the massacre through a very particular (and often literal) lens: the Olympic studio of the American broadcaster ABC, who were, for many hours, the only broadcaster to carry live coverage of the hostage situation occurring just 500 metres from them.

The film is effectively a chamber piece, its attention contained to the ABC’s smoky studio and the improvised, high-stakes decisions made by those who occupy it. On this day, the ABC’s sports producers morphed suddenly into broadcasters of a grisly and uncertain crisis – and were reluctant to surrender their role to their news division back in Washington.

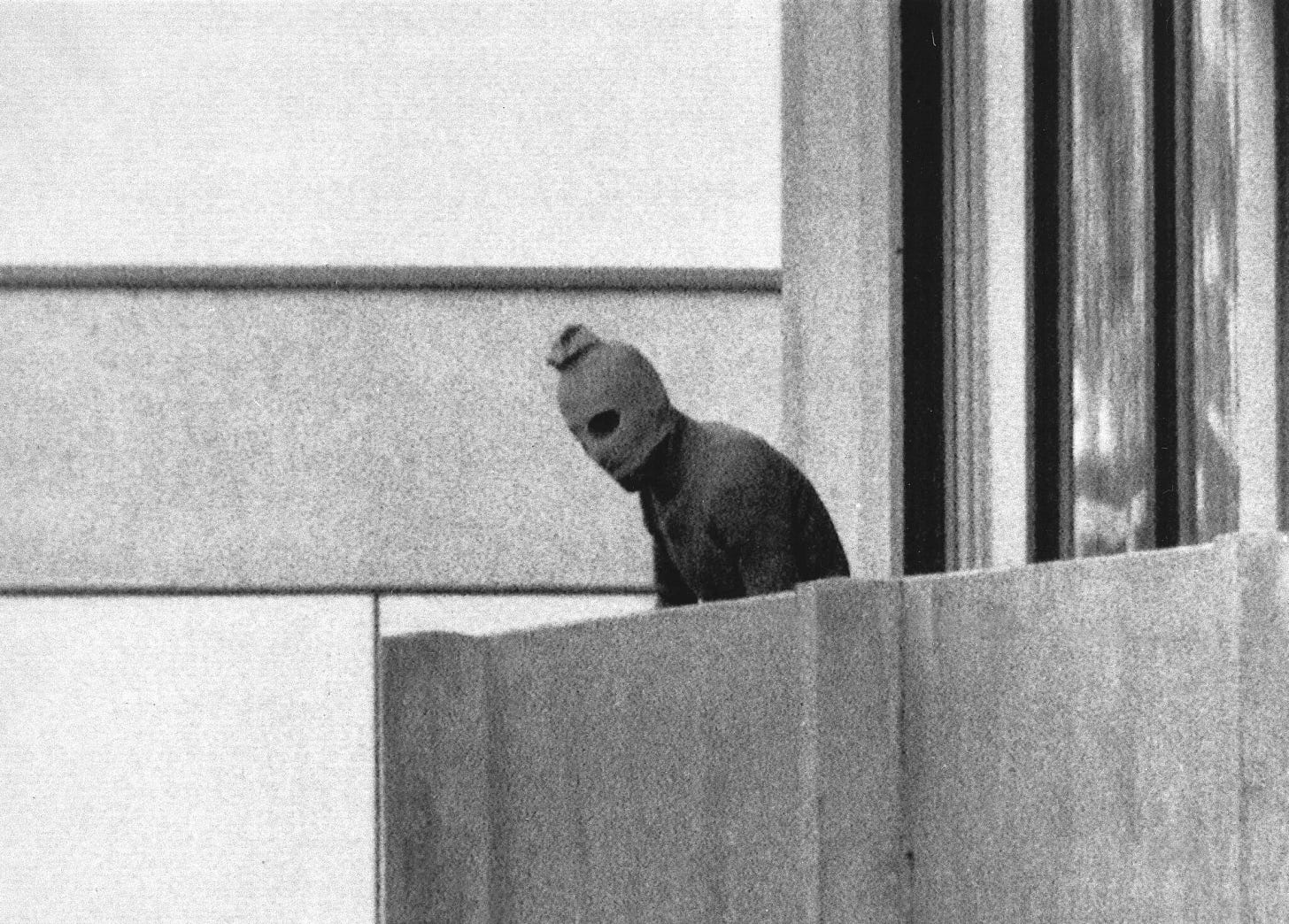

But if September 5 is a chamber piece, it’s one with a close view of the crisis unfolding outside it, and the film makes great use of the footage captured by ABC that day. Of the masked terrorist stepping out upon the hotel’s balcony; of negotiators meeting with the group’s spokesman at the foot of it.

The footage remains astonishing today: of police dressed as chefs delivering food in such quantities that they hoped they’d be asked to help deliver it to the rooms themselves; of the police negotiator asking the terrorist for a light for her cigarette; and live footage of athletes, just metres away, sunbathing and playing table-tennis as two Israeli athletes lay dead in their room.

None of that was the most consequential footage from that day – that would be the live coverage of the police operation to storm the rooms. If there were nearly a billion viewers of the crisis, some of those included the terrorists themselves. They were watching police movements on live television, and when this was finally realised, the operation was abandoned.

Refreshingly, for a film about journalism, September 5 doesn’t much glorify or sweeten the profession. We witness professional ingenuity under strain, but the audience doesn’t suffer from suspiciously articulate Sorkin-esque monologues in praise of their own brilliance.

The film captures (even if it sympathetically softens) the rude chaos of broadcasting live horror. And while we see much professional guile, for all of the ingenuity no one bothers to ask if what they’re broadcasting might be watched by the terrorists themselves. That penny drops late.

Instead, their work is rationalised very simply: “We must follow the story, where ever it goes”. A simple creed, offered as wisdom, but really an arrogant laissez faire. When E.J. Kahn reported from Munich for The New Yorker, in a long piece filed just a few days after the massacre, he recalled seeing photographers scream “Fascists!” at local police who were shielding Israeli mourners from their cameras. “To a photographer, there is no such thing as a moment of private grief,” he wrote.

As it was, the West Germans – in their conspicuous display of sweetness and historic disavowal – had once again made their country unsafe for Jews. And on live television, no less. Live footage would capture their haplessness too, as local police, untrained with weapons, much less counter-terror tactics, assumed sniper positions on roofs in broad daylight – men “disguised” in athletic tracksuits while wearing helmets and holding guns they weren’t sure how to use.

The next stage of the crisis occurred at the military base, where the captors were allowed to travel via helicopter with their captives, and where the ineptitude of German police was ultimately manifest.

The pre-established snipers had no communication with each other, nor were they told that the presumed number of terrorists had been revised upwards before they arrived. Police who occupied the jumbo jet – demanded by Black September to make their escape – abandoned their position at the last minute. Someone forgot to order the armoured vehicles, and when they were finally called, they were further delayed by the congestion created by the cars of civilian rubber-necks – police hadn’t thought to cordon the area off.

A long shootout followed, and amongst the chaos a rumour emerged that the shooting was over and all hostages had escaped. It was reported all over the world, and their families thought for a while their loved ones were safe, before the bloody truth became clearer a few hours later. “They’re all gone,” the ABC’s sports anchor, Jim McKay, famously said.

What happened next is another story – but enough to say here that Avery Brundage ensured that the Games continued. The Olympics were a force for unity, he thought, and abandoning them would be obscene – even in the wake of a massacre. Not for the last time did an IOC President mistake the Games for church, and himself for God’s head. On September 8, after a day of mourning, the heats for the men’s 1500 metres began.

What a story! I vividly remember the sensation of some of the broadcasts, even the masked figure is familiar. I can't say I'd like to see the film, but I feel I need to.