Days of Grace

The Life & Death of Arthur Ashe

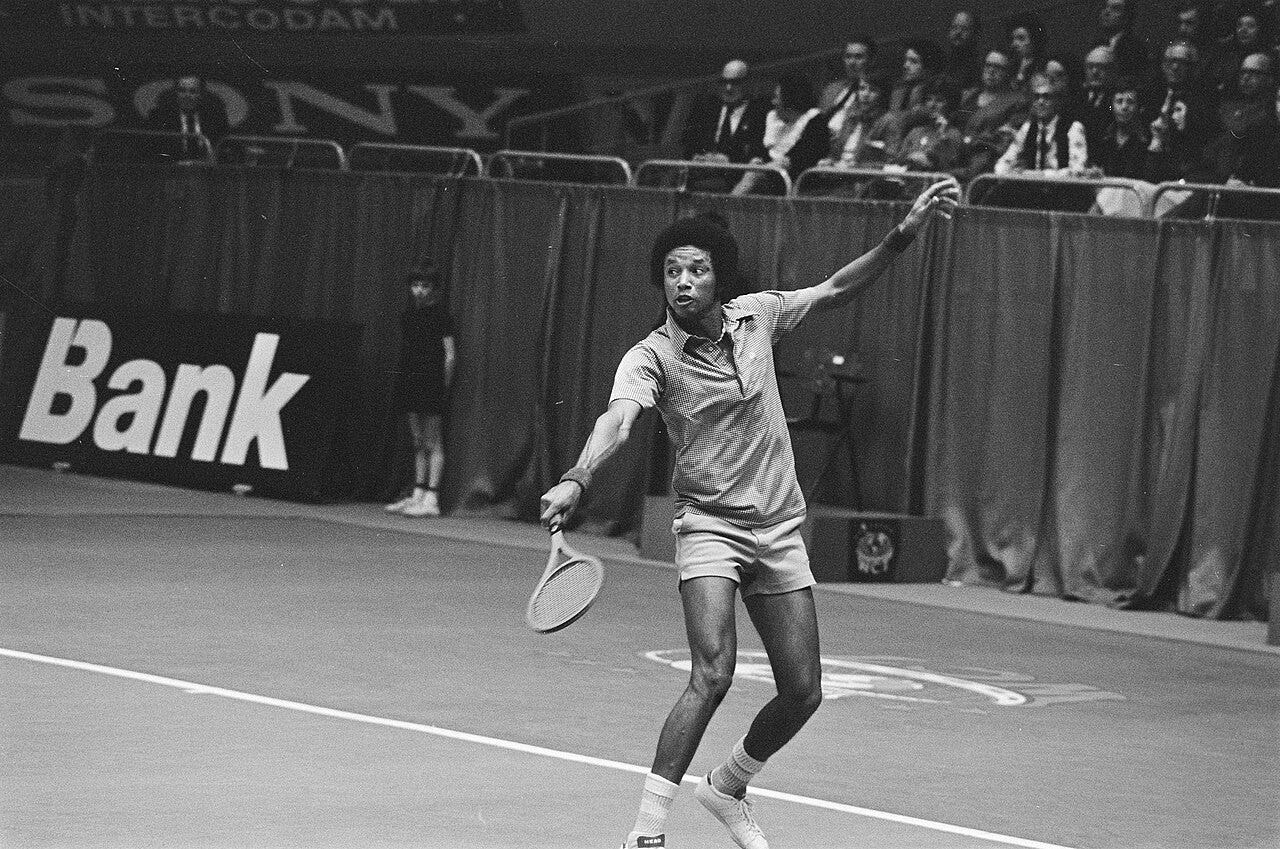

No one gave him a chance, and at times that included Arthur Ashe himself. An hour or so before the 1975 Wimbledon men’s singles final, where he’d meet the reigning champ and world No. 1 Jimmy Connors, a TV reporter asked Ashe about his confidence. “[It was] at its zenith, I guess, five or six minutes ago,” Ashe replied. “But now it’s all the way back down again. But I’ll be out there trying as hard as I can.”

Crisp, elegant, unusually candid – and his response gave a sense of the volatility of self-belief. Ashe would have to revive that confidence before the first serve, against a man he’d never beaten and who, at 22, was a decade younger than him.

Connors dominated men’s tennis during this period. He was maniacal, aggressive and famously obnoxious. He swore, he sulked, he mimed sex acts with his racquet. He was also thin-skinned and compulsively litigious, and at the time of the 1975 final was in the act of suing Ashe for saying he was “unpatriotic” for refusing to play for the United States Davis Cup team. “Imagine the sepsis of helpless loathing he must have inspired in his opponents,” Martin Amis once wrote of the great “asshole”.

Two nights before the match, Ashe had dinner with three close friends at London’s Playboy Club. At their table, tucked away at the back of the room, the four discussed tactics. Connors was a slugger, they agreed, but he depended on the speed of his opponent’s returns to generate his own. To deny Connors, they agreed, Ashe would have to deny himself and assume an entirely different style of play – one that emphasised soft shots, so as to oblige Connors to generate his own power, and plenty of lobs to thwart his characteristic charges to the net.

The strategy worked magnificently. Ashe won the final 6–1, 6–1, 5–7, 6–4, and a great upset was made. Fifty years ago, on July 5, 1975, Arthur Ashe became the first, and only, Black man to win the men’s singles at Wimbledon.

*

Arthur Ashe was born in the old capital of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia, in 1943. His mother, Mattie, died when he was six, and later he remembered her open coffin in the middle of their family room. Ashe and his younger brother, Johnnie, were raised by their father, an attentive and stern man, who cultivated his sons’ discipline and love of sport.

In the severely segregated city, “lily-white” tennis was an unpromising passion, and Ashe’s first coach and mentor, Dr Robert Johnson, reminded his charges that the behaviour of young Black men playing this sport “was to be beyond reproach”.

Ashe escaped the South for St Louis when he was a teenager and then left for California when he won a tennis scholarship at UCLA in 1963. He received excellent coaching there and for once was not restricted to prescribed areas to play. He began excelling in the juniors’ circuit.

Conspicuously calm, articulate and quietly self-possessed, the media would later describe Ashe as having a “majestic cool” and “icy elegance”, which was true but didn’t capture the flinty resilience he also possessed.

“You try to put your entire being – mentally and physically – on automatic pilot while you’re playing tennis,” he once said. “Everything is concentrated on the razor’s edge and you forget the score, you forget where you are, you forget what your name is. I feel that my body is floating within myself.”

For a time in the 1960s, as his star was rising, that cool detachment extended off the court as well. As the Civil Rights movement flowered and churches were bombed and young men hanged from trees, Black leaders came to suspect the conspicuously quiet Ashe of being, in the words of activist Harry Edwards, a subservient “Uncle Tom”.

During his youth, Ashe would later admit, he was overwhelmed. His ambivalence or reluctance to speak stridently wasn’t a matter of indifference. His father had preached discipline and respect for authority on the one hand, and yet he also experienced the danger of being a Black man in America. But it was more complicated still. “As a Black man in the American South your life is proscribed, and then in the ’60s you had Black ideologues trying to tell me what to do. All the time I thought: ‘When do I get to decide what I want to do?’ ”

A pivotal year for Ashe was 1968, and by September he had his first major title – the US Open. That same year, Martin Luther King Jr was murdered, and two months later so was Robert F. Kennedy – a man Ashe had campaigned with only the day before. Cities were on fire. The country convulsed. The Tet Offensive shocked Americans, most of who now understood that their government’s claim that the United States was dominating the Vietnam War was a lie.

“These things coalesced for me,” Ashe would later write. At the time, he was a military officer at the West Point academy but had long held doubts about the wisdom of a war that King himself had been publicly deploring since 1965. “During one stretch it seemed there was a funeral every day at West Point,” he wrote in one memoir. “I was saddened to see so many young men, so young they had not even been promoted to first lieutenant, brought back in boxes … Seeing the dead and knowing that a disproportionate number of young blacks were paying the ultimate price for faulty American policy moved me toward firm opposition to our involvement in Southeast Asia, even with my military status.”

Ashe became a public star, and one now sufficiently confident and clear-minded to speak when he thought something needed saying. Asked that year on television what had changed, he said: “[Initially] I was simply awed. I came from humble beginnings … But in these times, there’s a mandate to do something.”

He would become friends with Harry Edwards, his old critic, who would later say of Ashe that if you stripped away his gentility, he was “more militant than I was”.

*

Arthur Ashe had his first heart attack in 1979, aged 36. He’d inherited a bad ticker. His mother had suffered cardiovascular disease and his father had had a heart attack – Arthur Sr’s second – only a week earlier. Later that year, Ashe submitted to quadruple bypass surgery, and afterwards remarkably began preparing for his return to tennis. Further chest pains in 1980 obliged his immediate retirement and heart surgery was required in 1983, along with a blood transfusion. The blood Ashe received was contaminated with the HIV virus – a fact not discovered until 1988, by which time the virus had become AIDS.

Arthur Ashe was living on borrowed time, but his status as an AIDS patient was kept from the public. Ashe was anxious to retain his privacy – not least for his young daughter, Camera – and the family managed as much for four years. But one day, in 1992, an old friend – a former tennis player and now sportswriter at USA Today – knocked on his door. He’d heard a rumour that Ashe had AIDS and his editor had requested he try to confirm it.

Ashe was appalled and hedged irritably. It was all he could do: he neither wanted to lie to his friend nor concede the facts of his health to a newspaper. His friend left and Ashe felt sick, and when later he received a call from an editor at the paper asserting their right to investigate and then publish if they could confirm the story, Ashe knew his privacy was lost.

He sought to pre-empt the newspaper and called his own press conference. Before he met the press, Ashe and his wife, Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, sat down with their five-year-old daughter to delicately explain her father’s parlous health and the fact that life might soon change for her. “We had to tell her before someone, most likely some other child, taunted her with the fact that her father has AIDS,” he wrote in his memoir Days of Grace. “I could hardly look at her without thinking of how innocent she was of the import of this coming event, and how in one way or another she was bound to suffer for it.”

Then Ashe called a few dozen friends to let them know, before sitting at his desk to write the public statement he would give the next day. As he sat there anxiously pondering his speech, his daughter came into the room and offered her father a present wrapped in her tiny fist. When she opened her hand, there sat on her palm a Hershey’s Kiss wrapped in silver foil.

*

Ashe began the press conference with a joke: that he was here to announce that the Yankees owner had appointed him the club’s new manager. No one laughed. The press knew the score.

Ashe confirmed his AIDS diagnosis, then tearfully asked his wife to read the section of his speech that pertained to their daughter. When he resumed, he lamented that USA Today had “put me in the unenviable position of having to lie if I wanted to protect our privacy. No one should have to make that choice. I am sorry that I have been forced to make this revelation now.”

The ethics of this were debated extensively in public by journalists, and it was properly divisive. Some reporters were appalled at the presumptuousness of the invasion, not least because Ashe had been retired for more than a decade; others thought there was a higher principle of social utility, as when Carl Rowan wrote in the Chicago Sun-Times that “AIDS education was far more important than any man’s privacy”. It would be used as a case study in media ethics classrooms for decades.

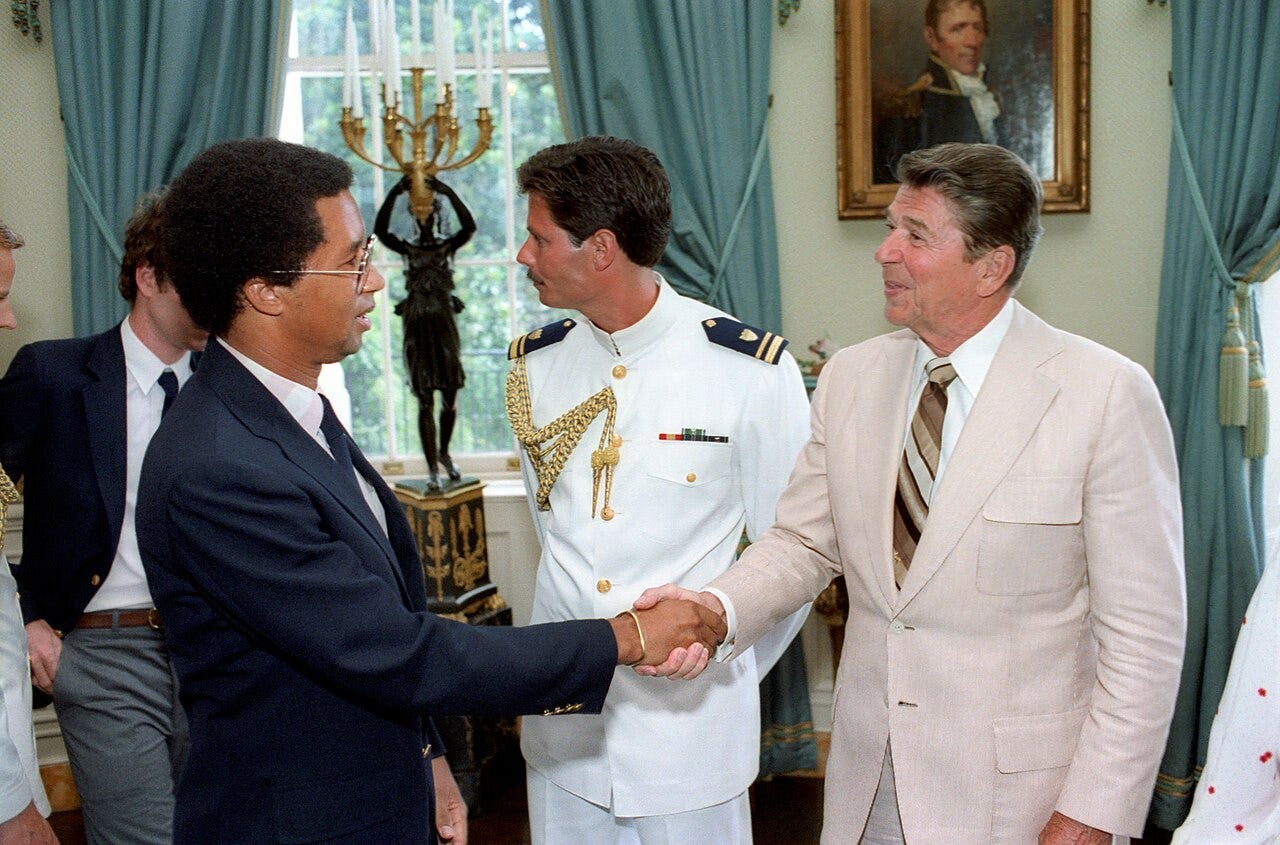

Ashe’s health declined sharply after this announcement. He maintained his business associations, though, and was grateful that commercial endorsements and board positions weren’t renounced when he declared he was a modern leper. He spoke constantly about AIDS and his disappointment in what he saw as the Bush administration’s indifference.

At home he wanted to spend time with his wife and daughter, all the while knowing the profound shortness of it. With a five-year-old, this meant being as natural as possible while knowing how unnatural the world’s gaze was and how blighted the moment.

In his last months, Ashe also collaborated with an English professor on Days of Grace. He wouldn’t live to see its publication – Ashe died in February 1993, aged 49, just 10 months after his public announcement.

In the book, he cites the letter he’s written for his young daughter: “By the time you read this letter from me to you for the first time, I may not be around to discuss with you what I have written here … You would doubtless be sad that I am gone, and remember me clearly for a while. Then I will exist only as a memory already beginning to fade in your mind. Although it is natural for memories to fade, I am writing this letter in the hope that your recollection of me will never fade completely. I would like to remain a part of your life, Camera, for as long as you live.”

Marvellous alright. I now read the back page of The Saturday Paper first - just like a true Aussie reads newspapers (and I never have before).

This is powerful and well done. Thank you. You seem to have a thing for athletes. The Foreman piece, for example. Even the Tesich piece glances at sports via Breaking Away. You should consider collecting them in a book.