Don't You Want to Live Before You Die?

The Coen brothers' "A Serious Man"

“There was a man in the land of Uz, whose name was Job; and that man was perfect and upright, and one that feared God, and eschewed evil.” – The Book of Job (KJV)

“No, of course not. I am the junior rabbi. And it’s true, the point-of-view of somebody who’s older and perhaps had similar problems might be more valid. And you should see the senior rabbi as well, by all means. Or even Minda if you can get in, he’s quite busy.” – A Serious Man

*

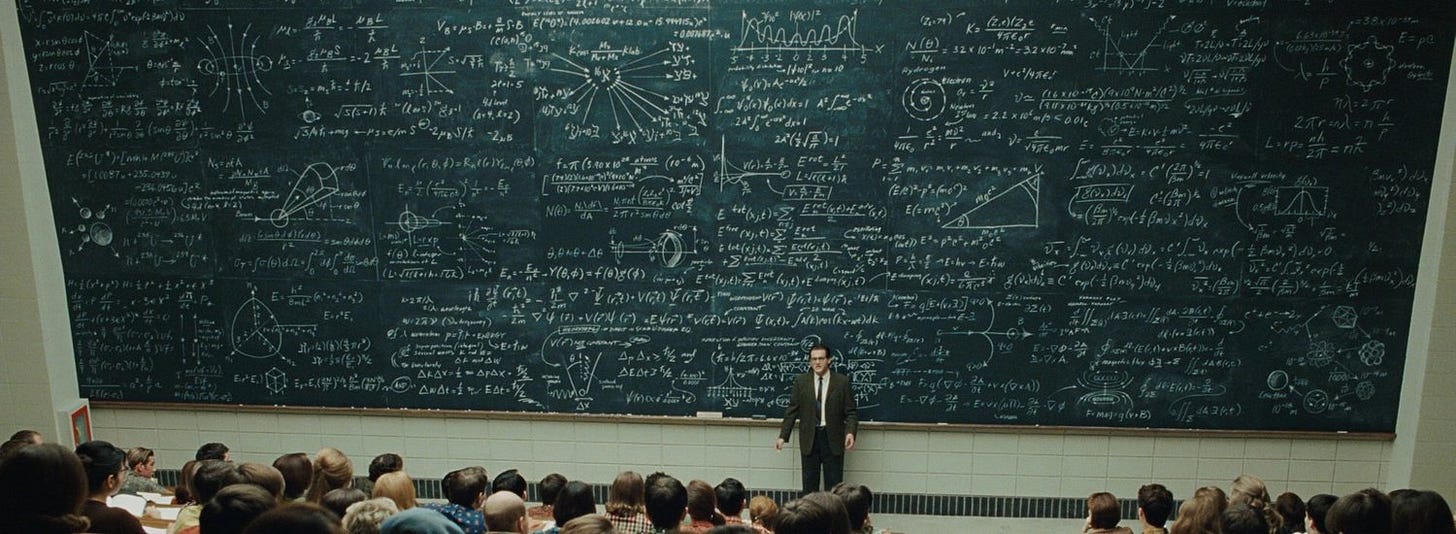

In A Serious Man (2009), Job is the charmless physics professor Larry Gopnik, and the land of Uz the Minneapolis ‘burbs of the Coen brothers’ boyhood. It’s 1967, and the hapless, bewildered Gopnik is in for a world of pain – God is ripe to cast his fire upon him.

At home, Gopnik is the father of two brattishly warring and indifferent children; his wife is about to declare her love for another man and instigate a costly divorce. At work, Gopnik’s consideration for tenure is being undermined by a series of anonymous, maliciously invented complaints alleging his “moral turpitude” and he’s being blackmailed by a student unhappy with his grades. He’s been cuckolded by the unctuous Sy Ableman, intimidated by a violent neighbour, and now domestically hosts his parasitic brother who’s in weird trouble with the law. And he seems to have no friends.

It only gets worse: his wife and Ableman demand his eviction from the family home. It’s cruel and illogical, but, as always, Gopnik submits and retreats to the seedy local motel, The Jolly Roger. His brother is arrested, twice, and shares his room. He has no idea how he might pay for the snowballing legal fees.

Has Larry Gopnik not been good? Has he not been pious? Has he not been professional, uncomplaining, loving and thoughtful? Has he not been an attentive father and kind neighbour? Has he not feareth God and escheweth evil?

He may have. But Larry Gopnik is also repellently passive, a nebbish mark for wolves. He submits to the smug manipulation of Ableman; to the hostility of his neighbour; to the callousness of his wife. He concedes his home, his reputation, his children’s indifference. He fights for nothing, having assumed that his basic decency would be cosmically rewarded.

Job said “The terrors of God do set themselves in array against me” and Gopnik feels the same. He wants answers. Why is he suffering so much? How and why does God speak? Where is wisdom to be found? The basic cosmic/ethical calculus that God rewards virtue and punishes sin cannot be found. And so, what is the calculus – if there is one?

Gopnik earnestly seeks counsel from several rabbis, each one ordinary monsters of vanity and glibness. Their counsel takes the form of oblique epithets and anecdotes, which are not so much gnomic as insensible. Baffled, Gopnik seeks others only to find again the same dissatisfaction. The mystery of his suffering remains – no, it’s been compounded.

In searching for cosmic answers in what appears to be a chaotic universe, Gopnik forfeits his own autonomy – and thus his own enjoyment and dignity.

*

It seems significant to me that much of the film’s diegetic music is provided by Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow, released in 1967, the same year in which the movie occurs. Their famous song “Somebody to Love” recurs throughout, its mood of anarchic carnality a counterpoint to the ostensible blandness of the Mid-West’s suburbs and the emotional prohibitions self-imposed by middle-class Jews.

There’s a spooky humidity to the song, a sense of yearning that’s transformed into something darker, and it’s notable how often this song (and, even more frequently, its album companion “White Rabbit”) features in movies set in the late ‘60s to suggest, or heighten, a sense of new freedom curdling into chaos.

Where is wisdom to be found? For Timothy Leary and his merry followers, it was to be found through the doors of perception, the ones opened by the ingestion of LSD. There were thousands of acid eaters at Altamont that infamous day when freedom curdled into chaos, and the plains of infinity became a muddy site of rape and murder. You can see Jefferson Airplane perform at the infamous Altamont Free Concert in the Maysles brothers’ classic verité documentary of it, Gimme Shelter, as you can see their set stopped when the Hells Angels – employed that day as security guards – invade the stage, punch unconscious their rhythm guitarist and break cue sticks over the heads of delirious hippies.

Not for the last time that day, performers will protest the violence of the bikies and the broader mayhem and bad vibes. Airplane drummer Spencer Dryden would later say that what lay before the stage “did not look like a bunch of happy hippies in streaming colours – it looked more like sepia-toned Hieronymus Bosch”.

But all of this is faint subtext to the particular chaos and suffering that visit Larry Gopnik. He didn’t seek to open any doors of perception, didn’t want to reimagine freedom or God’s moral calculus. And yet, and yet.

*

The Book of Job was beloved by Milton, who reinterpreted it, and by Edmund Burke, the 18th century philosopher of the sublime and the French revolution. But it took the arch genius of the Coen brothers to transform it into black farce.

In the Book of Job, God and Satan confer. God commends the moral greatness of Job, a man of unwavering piety and decency, to which Satan, wisely I think, suggests that his piety is merely a function of his well-being. Impoverish him, Satan says, and see how well his piety prevails. Satan continues: if man understands that He will reward virtue and punish sin, then virtue is likely nothing more than the product of self-interest.

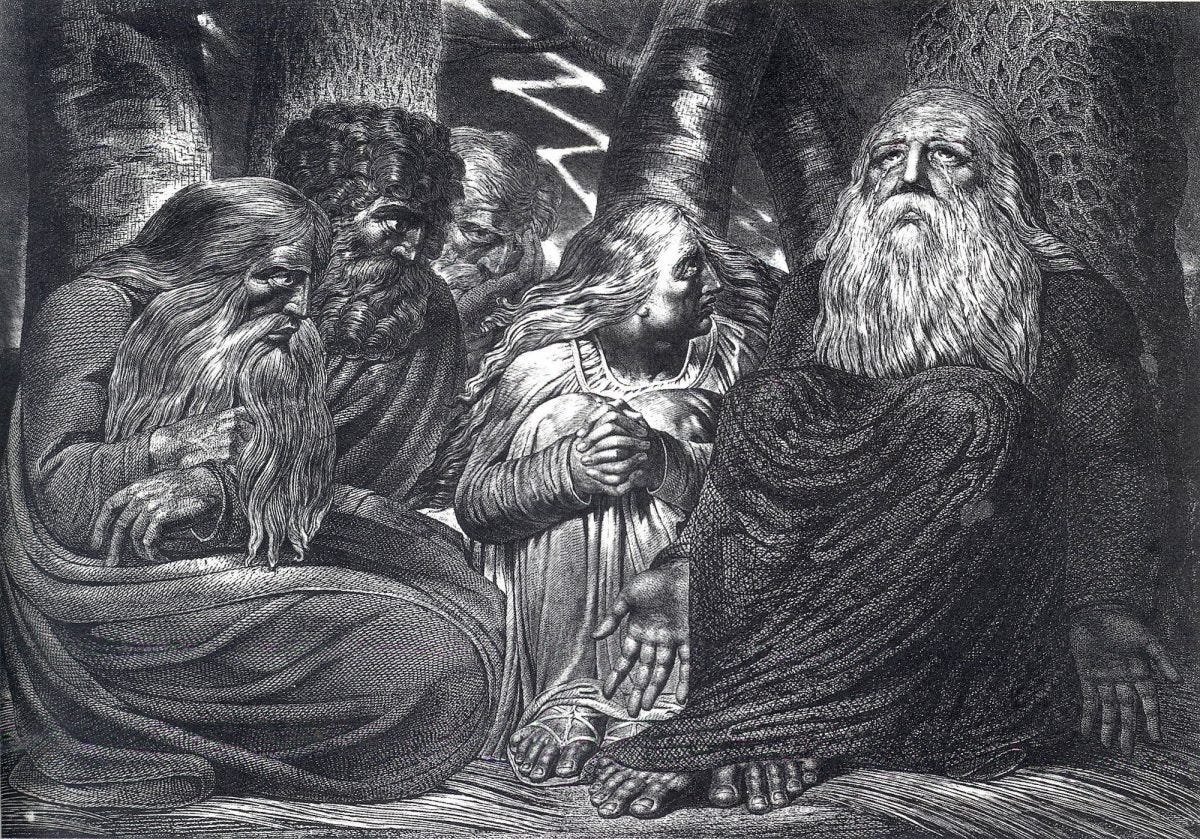

It’s a wager of sorts, and God accepts it and commissions Satan to inflict profound suffering upon Job. His children are killed, his house torched, his livestock butchered. Grotesque boils disfigure him, and he receives not the sympathies of his friends but their severe judgement: God is just, and Job must be wicked to have found such punishment.

Job is baffled, incredulous – but more, he’s gravely pained. He wants to die, and curses the fact that he was ever alive: “Let the day perish wherein I was born”. Job comes to question the moral calculus, but not God’s ultimate wisdom – his piety survives his suffering.

The Book of Job is largely made of a lengthy, poetic dialogue between Job and his judgmental friends. His friends suggest that God’s power can never be exercised in so brutal or arbitrary a manner; Job meanwhile understands his own righteousness. And so the two sides remain in pained incomprehension, and nothing between them is resolved.

Towards the end of the book, God delivers the ultimate flex of power. From a “whirlwind” God speaks to Job, but doesn’t care to explain his suffering to him – he merely invokes His own infinite wisdom. Where were you when I made the earth and the sky? He asks Job. Where were you when I made the stars and the moon? God is not only reminding Job of his vast power, but of its mysteriousness. “Declare if thou knowest it all” He rhetorically challenges Job.

God is perfect in knowledge, but that knowledge is not evenly shared and often withheld. In A Serious Man, Gopnik often hears others tell him to “embrace the mystery” but those who offer this advice seem to be acting, as Satan proposed, upon their own comfort – it’s advice offered complacently by those who aren’t suffering and who may assume that their absence of suffering is proof of their own rectitude.

But if Job – like Larry Gopnik – was moved to understand the purpose of his suffering, then the sudden appearance of Elihu in the dialogue offers something specific. Elihu criticises both Job and Job’s judgemental friends, and in doing so offers something of a synthesis of their painful verbal duel. He reminds them of the supremacy of God’s wisdom and says that it’s wrong to think that the righteous can’t suffer, and that their suffering may be useful even if its purpose is mysterious. Suffering, Elihu says, may “open the ears” of the afflicted.

To which the Coen brothers might say: Meshuggeneh. How absurd to search for meaning in chaos, and to surrender your agency in doing so? To live is to suffer and then again to suffer the friction between that suffering and a belief in a moral calculus that God himself has made mysterious.

One last word on the Book of Job and A Serious Man – there’s no Elihu figure in the movie. Not that I saw. No friend to sit with Gopnik’s suffering, and take it seriously, and attempt to reconcile things between the professor, his adversaries and God. No, our man can only agonise ineffectually, unguided and doomed. Pursuit itself might be happiness, Hemingway thought, but Gopnik’s pursuit for higher meaning is painfully fruitless and personally diminishing.

*

Burn After Reading is often dismissed, but it’s always been one of my favourites of the Coen brothers. Like A Serious Man, it’s a black farce, where the plot functions as a pinball machine and its characters as its balls. But in Burn After Reading, the characters are implacably ambitious – they arrogantly delight in their own agency, even if they misunderstand and exaggerate it. The characters, each breathlessly pursuing their own goals, rebound off each other. Their misapprehensions about what’s happening cascade comically, as so their hapless pursuits combine to resemble Kessler syndrome – the theorised state whereby space junk assumes a density so great that collisions endlessly multiply.

But poor Larry Gopnik is not motivated by ruthless ambition, but rather doomed by his passivity. If bad things happen to good people, then Gopnik encourages the fact by his pathetic inertia. But don’t think there’s a lesson here from the Coens either: the wretchedly smug Sy Ableman, a man who takes what he wants and shamelessly justifies it with psycho-babble, is killed suddenly and randomly. His self-possession has not protected him from the randomness of the pinball machine.

*

This piece of mine is a failure, not least because it has none of the humour of its subject. A Serious Man is seriously funny, and it’s also – unsurprisingly – technically masterful and filled with brilliant performances. So let me share something A.O. Scott wrote about the film upon its release, which I think vastly more insightful than anything I could say about the craft of it:

“Their insistence on the fundamental absence of a controlling order in the universe is matched among American filmmakers only by Woody Allen. The crucial difference is that the Coens are compulsive, rigorous formalists, as if they were trying in the same gesture to expose, and compensate for, the meaninglessness of life.”

That is, in making fables about the comic meaninglessness of things, the Coen brothers found their own meaning – in fact, they found a galvanising and life-defining purpose. And they know the value of laughing about it all, too. “A sense of humour is nothing more than common-sense dancing,” the late critic Clive James said. I think they’d agree.

Towards the end of the Book of Job, God speaks to Job through a “whirlwind” where he reminds him of His infinite but inscrutable wisdom. In an epilogue, we learn that Job’s wealth is restored, that he fathers more children and that he lives to 140 years old.

At the very end of A Serious Man there’s a whirlwind too – an impressively powerful tornado – but no divine words are spoken from it and, after a phone call from his doctor, there’s scant chance that Larry Gopnik will enjoy the same longevity as Job.