A slightly different version of this piece first appeared in The Saturday Paper.

In the rag shop of jail, John Healy found chess. It was 1973, Healy was 30 and serving time again for begging – the vagrancy laws of Britain then considered one an “incorrigible rogue” after a third charge. This was his fourth or fifth, he’d lost count, and while he’d done time for assault and public disorder too, it stung that he was back inside for asking strangers for smokes when other cellmates were in for rape.

Healy was jailed in North London’s Pentonville prison when he met Harry Collins, aka the Brighton Fox, a charming crook who once beat a murder charge. He was an alcoholic like Healy was, and in the shop one day Collins said something fabulous to him: “Listen, if I told you about a game that if you were waiting for seven o’clock on a Sunday night for the pubs to open, and you was playing this game, you’d forget the pubs wasn’t open and not worry about the time, what would you say?”

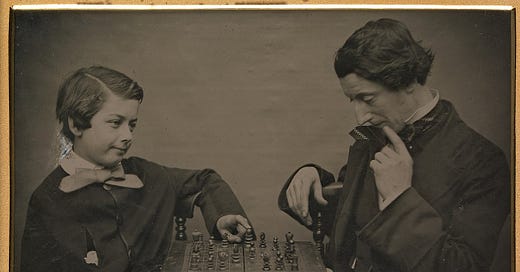

Healy said that it sounded like bullshit, but was happy to hear more. He had plenty of time. And it was then that John Healy – self-described wino and violent vagrant – was introduced to chess, first played on a board drawn with biro on the shop’s table and with pieces made from scraps of paper.

The Fox was good, very good, but within a fortnight Healy was beating him. And then something happened. In jail, Healy suffered from alcohol withdrawal. He’d sweat and shiver; his dreams were grotesque fantasias. But now he’d found a replacement addiction. John Healy is an extreme man, and he abandoned booze and embraced chess with astonishing severity. “Chess is a jealous lover,” Healy wrote in his memoir, 1988’s The Grass Arena. “Will tolerate no other, especially in the form of too much drink. I gave myself to her completely, body and soul, and for the first time in my life I began to live without a constant nagging desire for drink. I was like a person who finds God, only this God was a warrior made out of wood who derives his power from man.”

Upon his release, Healy’s probation officer arranged rehab and helped buy him a chess set. Healy dreamed of playing grandmasters. And he literally dreamed of chess moves. Extravagant ones. Sacrificial ones. Triumphant ones.

*

John Healy was born to poor Irish parents in London in 1943. He belonged nowhere. To his vicious father, his Cockney tongue was another reason to bash him. In the still bomb-cratered streets, it was his Irishness that local thugs punished with their fists and boots.

At home and under duress, Healy would recite the Catholic Catechism – and asked to acknowledge and absorb the suffering of the Virgin Mary. He also absorbed the blows of his father, and came to think that life was wholly defined by “punishment and suffering”.

His father’s violence was implacable, and for a long time Healy thought he deserved it. The ancient instinct to please your parents, to secure their validation, stayed with him even if the logic of his father’s violence remained baffling. It was his father that decided to move them to England, not he – and yet it was his father who berated his English accent.

When young Healy returned home from school, bloodied by local goons, his injuries invited not his father’s tenderness, but his wrath. Healy’s beatings were proof of his son’s provocations, his father thought, or at least of his weakness. And yet, when Healy got older and bigger, and no longer flinched at his father’s strap, his bold defiance became unforgivable too.

Healy couldn’t win, but at least he realised this young. Realised that his father’s violence had nothing to do with him – that his father was bitterly captive to self-pity and projected his resentments upon his children. And so, it didn’t matter what he did. The game was rigged. Better to move on. And here was a brutal discovery of freedom: of no longer wanting or needing your parents’ love.

*

John Healy left home and drank. He drank a lot and to fund it he joined a boxing gym as a paid sparring partner. He was a promising talent, but after showing up pissed too often he was asked to choose between boxing and drink. He chose drink, and sold his trophies for their silver. From the age of 15, he was homeless.

In his early twenties, and after several arrests for vagrancy, his probation officer suggested he join the army. So he did, where his boxing skills were immediately noticed and he was given liberties to train for the battalion’s fight contest. Five companies comprised the battalion.

Healy, despite spending his days drinking, breezed into the final. He was surprised by how easy it was. But then came the championship fight, against an opponent he quickly realised was superior. His preparation that day involved several whiskies and fags in the boozer.

Healy was smashed by a left upper-cut, and the world spun. To steady himself, he gripped his opponent – to both keep himself up, and to buy time while the spinning slowed. The crowd booed – such clinches were thought boring and sneaky – but the tactic worked. Healy was outclassed, but managed a severe blow to his opponent’s eye. It poured blood, and Healy insisted upon aggravating the wound. He exploited his opponent’s partial blindness and won.

Not long after, Healy, as the battalion’s new boxing champ, was dishonourably discharged for drunkenness and brawling. The streets called again.

*

The “grass arena” was a London park occupied by various schools of vagrants, and a site of murder and deranged depravity, so much so that Healy came to think of it as a gladiatorial arena. The “schools” were tribes, and territory was violently defended. There was nothing tender or redemptive here. Corpses were picked for their belongings; necks were fatally slashed with broken bottles.

The days of the grass arena were measured by the volume of your bottle, and great cunning was spent finding a place to sleep. The vagrant tribes were made less in loyalty than from the necessity of collective strength, and a fallen comrade’s pockets would be cleaned without hesitation.

Healy’s memoir is not filled with artful excuses, but plain, dramatic descriptions of psychopathy and sickness. The grass arena is defined by all kinds of filth, and congeniality is welcome but always contingent.

And all the time, Healy was seeking to quell “The Tension” – his supreme anxiety, which was only worsened by his time on the streets. “The anxiety that felt like I couldn’t relax without a drink,” he wrote. “In a way I was like Siamese twins with my invisible lump joined on to my neck and back. I don’t know if twins give each other any pain, but my fucking twin lump was murdering me and I couldn’t get away from the bastard.”

*

Upon his prison release in 1973, and having replaced booze with chess, Healy made a spectacular rise. He was soon playing county champions, and beating them. Then international masters. His dream of playing a grandmaster was realised when he played Soviet champion Rafael Vaganian in a draw. Soon, he was successfully playing simultaneous games blindfolded. Newspapers had a great story.

But John Healy was also embittered and traumatised. His hands shook, and the snobbery he found could turn his brain red. He was kicked out of a tournament after belting an opponent who had smugly referred to his homelessness. Healy wrote in his memoir: “Never mind that I didn’t belong to their school, wasn’t I a chess player now – just like them? Nothing less than the best behaviour would be tolerated, old boy. Part of the code is to shake hands, win or lose, with friend and foe alike. This ritual is repeated before and after each game, regardless of results.”

One thing I love about The Grass Arena is Healy’s contempt for politeness – a thin, bourgeoisie virtue that often covers for mediocrity. Healy sees politeness (as opposed to respect) as another currency of class, something easily exchanged by its born members and of which its absence can be pointed to as proof of impropriety.

Our codes of civility are often a middle-class game than a virtue, and like Healy I prefer the meatier qualities of loyalty, courage and candour. They’re less easily faked.

*

Healy played chess for a decade, then dropped it. After the bottle, perfectionism might be his heaviest burden. He knew that the best had adopted the game when they were toddlers and not thirty-year-old inmates. He also knew that competitive chess aroused his forbidding anxiety. Chess was once a blessed escape, but was now aggravating the evil twin.

In 1988, Faber & Faber published his memoir. It sold well, and Healy suddenly found the media circuit and the strange acclamations of publishing’s liberal middle-class.

The publishing world had a hit book: it brought to the middle-class tales of extreme squalor, while also, in its very publication, a promise of the author’s personal redemption. This was catnip for newspapers, and gratified the moral vanity of its publishers and effusive critics. The liberal middle-class love nothing more than championing an underdog – so long as they don’t have to get too close, or properly accept the virtues and risks of their work.

*

In 1991 – the same year that the BBC released a film of the book – Faber & Faber pulped it, and disavowed Healy. The precise reason remains contested – it’s messily ventilated in the 2011 documentary Barbaric Genius – but Healy’s bitterness expressed itself violently. He may, or may not have, threatened to kill an editor with an axe. Which would be fair grounds to drop an author, I think, but then the threat seems to have been hyperbolic. I tried contacting Healy for this piece, but, through an agent, he declined an interview.

In 2008, Penguin re-released the book as part of its “Modern Classics” series, and Healy resumed simultaneous chess games to help promote it. Still, his various manuscripts were not picked up.

Maybe they’re no good. I think of Healy as a rare renaissance man, who’s tasted true squalor and adapted in fascinating ways, but The Grass Arena neither deserved its hyperbolic celebration nor its subsequent cancellation. Healy’s literary talent was over-praised and his threats anxiously exaggerated.

Still, it has been a remarkable life – the man has excelled at everything he did, including self-destruction.