Norman Mailer hated plastic. Like, really hated it. This “excrement of oil” was “the spiritual equivalent of political correctness” he once said, and he was disturbed by the thought that babies’ toys were made from the stuff, thus introducing us all to its cold, deadening effects from day zip.

It was worse than this, though. Mailer thought plastic caused cancer, and not in the obvious way – not through physical sickening – but through more mystical corruptions. It deadens people, Mailer said, by divorcing them from tactile pleasures and the natural materials of the earth. It was all part of modernity’s air-conditioning of the soul.

He went further, actually, when in 2000 he lamented the declining use of precious metals in tooth fillings. Having mercury in your mouth, he said, allowed for “a certain companionship with the devil – contact with occult forces”.

Hilariously, in 1965, when Mailer began building a seven-foot-tall model of Mile High City, his concept for a “vertical city of the future more than a half mile high” he did so with Lego blocks, which are made, of course, from the malign excrement. But the material spooked him, and he thought the sound of the blocks snapping together was “obscene”, and so he mostly had friends assemble the colossal project under his direction.

In what could serve as a metaphor for Mailer’s messy, domineering ego, when a museum showed interest in taking custody of the model some years later, it proved too large to be removed from his Brooklyn home without dissembling – something Mailer refused on account of his fear that it could not be re-made exactly as it was. And so it stayed, awkwardly, in his home for decades.

I was thinking about Mailer’s kooky contempt for plastic again this week, while reading about Grimes’ pronouncements on artificial intelligence, the future of music, and her partnership with a “Berlin-based tech-collective” that designed Endel, an app that creates “AI lullabies” or, if you prefer, “sleep soundscapes”.

While Drake and Ice Cube were raging against creepily authentic-sounding AI counterfeits of their voice and music, Grimes was telling the Brooklyn Vegan how she’d learnt to stop worrying and love the singularity. Her faith wasn’t new. “I think A.I. is great,” the musician, who now goes by “c” – as in, the symbol for the speed of light – told the New York Times in 2020. “I just feel like, creatively, I think A.I. can replace humans. And so I think at some point, we will want to, as a species, have a discussion about how involved A.I. will be in art.”

As good as Visions was, I won’t take instruction on art and human nature from a woman who married Elon Musk and called their daughter X Æ A-12. As much as Mailer lurched into lunacy, narcissism and appalling violence, if I absolutely had to choose between his mystical primitivism, and Grimes’ ostentatious futurism, well…

In most of Grimes’ pronouncements about art, I sniff the vapours of a very particular type of pretension – the person that believes themselves open-minded, avant-garde, and courageous about the future, and demonstrates these virtues through a conspicuously radical faith in technology. I always get the feeling with Grimes that she’s desperate to tell us how far-seeing she is – a prophetic sprite, encouraging us to slip the surly bonds of humanity. “I feel like we’re in the end of art, human art,” she said in a 2019 episode of the Mindcast podcast. “Once there’s actually AGI [Artificial General Intelligence], they’re gonna be so much better at making art than us... once AI can totally master science and art, which could happen in the next 10 years, probably more like 20 or 30 years.”

In the New York Times interview, Grimes/c spoke of her desire to “kill” copyright, and to serve as a “guinea pig” for AI. She’s now moved closer to that, recently tweeting that she was encouraging anyone to clone her voice to make music, and that she’d “split 50% royalties on any successful AI-generated song that uses my voice… Same deal as I would with any artist I collab with. Feel free to use my voice without penalty.”

You’ll be surprised to learn that the “Berlin-based tech-collective” behind Endel have a manifesto, in which they declare their belief that the app will “reshape our collective future”. They believe that “we’re not evolving fast enough” to cope with “information overload” and the answer to this hostile bombardment is not less technology, but more. “We need new technology to help our bodies and brains adapt to the new world.” Specifically, their technologies, which promise to “deliver static mindfulness content that is no different from what people used 100 to 1,000 years ago”.

I suppose there’s not much coin to be had by encouraging folks to turn off their fucking phones and go hiking for the weekend. Or, I don’t know, share a spliff with friends beside a lake. But such are Grimes’ business partners.

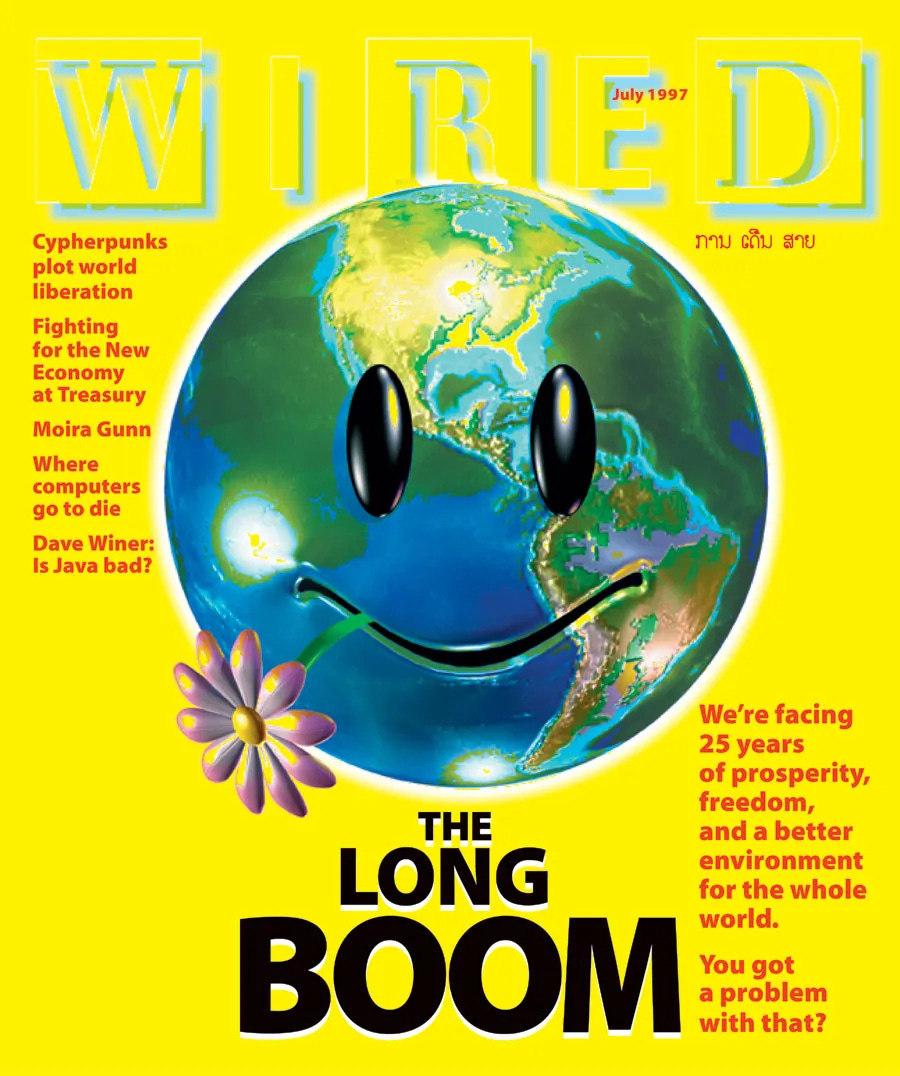

Twenty years ago, I saw the same pretentious credulity about the internet generally, and then again with social media. Sermons about the nobly transformative, democratising influence of social media were perhaps at their most annoyingly immodest during the so-called Arab Spring in 2010. This was the moment when Time magazine gave their Person of the Year to “You” (2006), Mark Zuckerberg (2010), and Protestors (2011), and the accursed TED Talk circuit was swollen with technologists and futurists and other fashionable grifters. But the Arab Spring largely went nowhere, “the uprisings… produced modest political, social, and economic gains for some of the region’s inhabitants… but they also sparked horrific and lasting violence, mass displacement, and worsening repression in parts of the region,” according to a 2020 report from the Council on Foreign Relations.

Here’s some more testimony, from the Tunisian academic and writer Haythem Guesmi, specifically about the exaggerated role that social media played:

During the early days of the Arab uprisings, when many activists were using Facebook and Twitter to organise and amplify their demands, the social media giants seized the opportunity to brand themselves as platforms for political activism and resistance. To this day, numerous media outlets run the claim that “social media made the Arab Spring” and that it was a “Facebook revolution”… social scientists have repeatedly busted this myth.

They have indeed. It didn’t seem to occur to many, at least not to those invited to give a TED lecture, that the internet’s various powers might be exploited by the very tyrants it was being celebrated as a weapon against. Since 2010, the internet has successfully been censored and used as a surveillance tool by autocrats. And 11 years after the Tunisian street vendor, Mohamed Bouazizi, set himself alight, it was social media that helped radicalise the American public, and then facilitated their murderous insurgency upon the Capitol.

At the turn of the century, it was a smug article of faith that the internet could not be meaningfully regulated. In 2000, President Clinton famously said that trying to control the internet was like trying to nail jelly to a wall, and that liberty would flourish from screens and buttons. I knew plenty who shared this belief, who saw the internet as an anarchically liberating force and scoffed enjoyably as older generations struggled with their illusions about control.

But the assertion was dead wrong. In 2000, China launched its Golden Shield Project – otherwise known as the Great Firewall of China – a titanic, state-run system of internet surveillance and censorship which has now had a quarter century to perfect itself. Intimidation also plays its role: VPNs may help you circumvent outlawed websites, but the penalties for doing so are extreme. Meanwhile, Russia seems close to launching its own domestic internet, entirely removed from the rest of the world. Iran’s secret police use the internet to surveil – and intimidate – its diaspora, including residents here in Australia. They’re not alone in doing so.

Crypto was another example of pretentious, unqualified celebration. But it’s largely a rort, which nonetheless developed an insufferable ring of credulous fanboys who loved to see themselves as High Priests of the Future – even if they didn’t quite understand what it was they were proselytising.

I wasn’t embarrassed 15 years ago by my scepticism, and I’m not now. Social media is a cancer, the ‘net is used just as well to stalk as it is to commune, Facebook is a grossly creepy and exploitative surveillance racquet, and so on and so on. I’m not a radical objector to new technologies – only to fashionable optimism that either serves as virtue signalling or as a means to fleece marks. Here's me in 2017, and today you can fairly easily replace “Facebook” with “TikTok”:

Today, the utopian dreams of the ’60s are most vividly present in Silicon Valley, argued journalist Franklin Foer in this year’s breezily polemical World without Mind: The Existential Threat of Big Tech. Foer is far from the first to link Californian hippies with the libertarian ethos of the Valley. Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog, a magazine first published in 1968, was a legendary tract of the counterculture. Offering “access to tools”, it sought the promotion of self-sufficiency by publishing articles and product reviews on almost everything. Carpentry, bee-keeping, growing dope. Steve Jobs once referred to it as a “generational bible” and a precursor to Google’s search engine. It ambitiously sought a blissfully collaborative, non-hierarchical world – which was precisely the same dream for the internet.

You won’t be surprised to learn that, in 2017, this utopia hasn’t quite been fulfilled. Having established the greatest surveillance operation in history, Facebook now serves us the news – fake or otherwise – it has determined we’ll like. It hardens our cognitive shells with a medium that was designed, in the words of one of its initial investors this year, to addict us. At last count, Facebook had two billion active users.

Facebook, Google and Twitter’s usefulness to political mischief – and its swallowing of online ad revenue – finally attracted the attention of the US congress this year. Adam Schiff, a Democrat representative on the House Intelligence Committee, fingered the health of the utopia: “Part of what made the Russia social media campaign successful [in the US presidential election] is that they understood algorithms you use that tend to accentuate content that is either fear-based or anger-based.”

It’s a supreme idiocy to reduce the value of the internet to a good/bad proposition – technology assumes a moral or civic value according to its use, and those uses are myriad and contradictory. Of course they are. We contain multitudes, and freedoms are used both constructively and abusively. But, Foer argued, we have marvelled at the giants’ life-changing technologies for too long, at the cost of paying attention to their tax-dodging, monopoly-making, privacy-eroding ambitions.

This is all just a long prelude, really, to an admission: the sudden developments – and warnings – about AI-generated art have left me faintly depressed. I’m not alone. Ice Cube recently called the cloning of his voice “demonic”, while Nick Cave described ChatGPT’s attempt at emulating his lyrics as “a grotesque mockery of what it is to be human”.

One reason for the delay of this piece (I’m sorry) is that I’ve been trying to understand and make coherent the low-hum of spiritual nausea I’ve felt recently. But I still can’t.

I think I’m probably irrationally alarmed. I’m also certain that no AI, as currently constituted, can replace me. Not yet. But unemployment isn’t my concern here. It’s a much more complicated fear of redundancy, I suppose, a sense that long-held assumptions about the humanity of art are being tested, my complacency slapped.

But it’s even more personal than this. I am one of those people whose identity, whose very self-conception, is intimately tied to what I do. When I take professional leave, I don’t stop writing – I just write other things. It’s always been this way. I’m not celebrating the fact – it’s probably deeply unhealthy – it just is. I’ve really never wanted to do anything else but write.

And so I find myself flirting with AI’s capacity for imitation. Here's ChatGPT’s response to the request: “Write something about De La Soul in the style of Martin McKenzie-Murray”:

De La Soul's impact and significance remain unassailable. Their unyielding commitment to artistic integrity, their willingness to challenge conventions, and their refusal to compromise their vision have made them true pioneers in the realm of hip-hop. In an industry often plagued by fads and commercial pressures, De La Soul has stood as an unwavering beacon of creativity, reminding us that the power of music lies not in its conformity, but in its ability to challenge, provoke, and inspire.

Excuse my defensiveness, but note the cliches, the reliance upon stale adjectives, and the absence of specificity. The sum of this is tedium. That paragraph is charmless and numbing, and yet it could have appeared in just about any publication. ChatGPT writes as well as at least half of working journalists today. Which is unsurprising: in this example, it’s simply aggregating, and re-organising, the existing pools of PR slop already published by humans.

So what am I afraid of? Have I confused my general exhaustion with some inchoate existential dread? Or are we genuinely serving as willing executioners of our own agency and human pleasures? And, yes: I know similar arguments/fears have long been made about the use of synthesisers, say, or sampling (of which De La Soul were exemplars). But cloning things seems categorically different, no?

And what is Ice Cube afraid of? Is he simply guarding his intellectual property, or is he spooked by the thought that he might be replaceable? That the specific thing that he does – the idiosyncratic, creative, personal, profitable and fame-making thing – might now be cloned and infinitely re-imagined by a machine?

It’s demoralising and disorienting. It’s also deeply strange. It might also be, if you’re Ice Cube, demonic – and I suspect Norman Mailer would have agreed. (Mailer’s hypothetical agreement, of course, isn’t necessarily a good thing.)

But I’ve spent plenty of words here saying very little at all. I’m still not sure about things; I haven’t thought them through enough. This piece is scattershot. A machine would consider it inefficient. And for the provision of information, it is. It’s digressive, unsure, imprecise. It lacks confidence, clarity.

But hey, at least a human wrote it. And if you’ve read this far, you’ve at least had some communion with another human’s consciousness – messy and confused as it is.