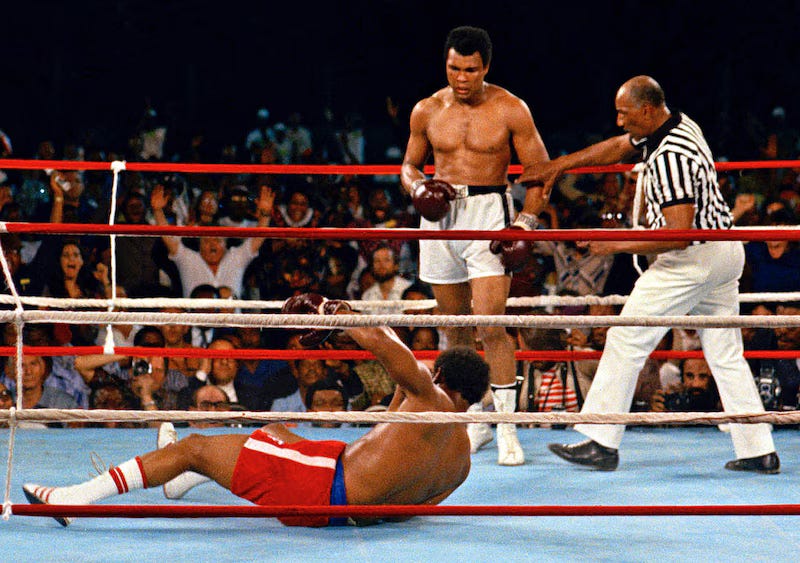

Poor George Foreman. Unloved and outwitted, he now lay vanquished on the canvas before a huge crowd made euphoric by his defeat. That night in Zaire (or morning – the fight was held at 4am local time as to accommodate a US television audience) would cement the legend of Muhammad Ali and plunge Foreman into years of depression and obsessive self-pity.

It wasn’t supposed to go this way.

It was 1974, and the world would soon watch what would become one of the most famous fights of all time. Arranged by Don King, the ex-con turned fight promoter, the “Rumble in the Jungle” would be hosted by Zaire and the fight’s handsome purse provided by its dictator, Mobutu Sese Soku.

King sold the fight as a “return to the cradle of civilisation” and a celebration of black culture – artists BB King and James Brown were flown to Zaire to perform too – but was borne as much by King’s desperation. Having just been released from prison for stomping a man to death, King was struggling to find either the money or the venue in the United States for a fight between Foreman, the current and undisputed world heavyweight champ, and Ali, a man who had not held the title since 1967. King’s public ascendency depended upon it.

So, here we were. Kinshasa, 1974. The year before, at the age of 24, Foreman claimed the title by defeating one of the greatest of all time: Joe Frazier. He demolished him. Before the final knockout, Foreman had felled Smokin’ Joe another five times with a power that arguably not even Sonny Liston or a young Mike Tyson could match.

Muhammad Ali was 32, seven years older than Foreman, and no-one thought he could win. Bookmakers had him as the rank underdog, and sportswriters privately assumed he’d be badly injured – or possibly killed.

In Zaire, Foreman had already perfected his aura of intimidation. His air of sour pitilessness was modelled on his hero, Sonny Liston, and while Ali ingratiated himself with locals, and delighted the press with comic insults of his opponent, Foreman rarely said much. In press conferences he sat solemnly, a quiet guru of extreme violence.

The atmosphere of the fight soon eclipsed the champ’s favouritism. As Foreman wrote in his 1995 autobiography, the fight had become a “morality play” and its protagonists agents for “good and evil”. Foreman quietly resented that he’d popularly been cast as the agent of darkness, not least through the canny PR work of Ali who countered his inferiority in physical strength by cultivating the country’s hostility towards his opponent. “He’s in my country!” Ali only half jested during a sparring session.

Ali was a balletic genius, but he was also cruelly gifted at mind games. In this, he was shameless, and rarely hesitated to use race to occupy the minds of adversaries – as when he called Joe Frazier an “Uncle Tom” or questioned the authenticity of Foreman.

And so, on October 30 1974, the two met for the first time in the ring. Having promised for weeks that he was “gonna dance”, Ali quickly retreated to the ropes. For round after round, Ali didn’t dance but leaned back on the ropes and absorbed astonishing punishment. And while Ali took the blows, he grinned and provoked Foreman further: “Is that all you’ve got, George?”

Furious and impulsive, Foreman didn’t ease up and allow Ali to come to him. Instead, he spent himself murderously pummelling his opponent on the ropes until, in the eighth round, Ali finally sprung off them and felled an exhausted and imbalanced Foreman. The sly fox was triumphant and the world was stunned.

*

Things got dark very quickly for George Foreman, and after the fight he became “depressed beyond recognition”. That heavyweight belt, he later said, was central to his very identity, and it was especially intolerable that it had been taken by the lippy underdog and smiling assassin of his character.

For months, Foreman relived the fight whether he was awake or asleep. It commanded his thoughts and consumed his dreams. He obsessed over it, replaying the fight as it was and then replaying it as it should have been. Foreman felt that he’d been “stripped of my manhood”.

Foreman was already an angry man, but his rage now became overwhelming and personally destructive. Few could stand to be around him, so volatile and seething was his self-pity. He raged, plotted and mourned his reputation. He was convinced that his water was drugged, and that the referee had shortened the count. He became, by his own admission, paranoid and unpleasant.

In that first year after the fight, he sought the comfort of several old girlfriends, who came to him and were then berated for their sympathies. Some would stroke his arm after he woke from a bad dream, and he would slap them away. He both wanted their attention, and reviled it, and Foreman describes in his first autobiography a terrible cycle of needing the attention of women, but then resenting their tenderness for what it revealed about his own vulnerability. Of one girlfriend, he wrote: “She knew I was in pain, and tried to be patient with me. But my insults soon wore her down.”

The great fighter also became terribly self-conscious. His ego was tethered to the world title itself, and, having lost it so surprisingly, Foreman assumed that friends, family and the general public were now laughing at him. He became paranoid about paternity claims and sacked his manager and coach. He lost lovers and friends and felt that he needed a new Rolls Royce in which to visit his old, impoverished neighbourhood in Houston.

It was a sad state for a powerful man, and in this long night of the soul it was not God, his mother or his various children that he most thought of. No, it was that clowning prince, Muhammad Ali.

For years, George Foreman loathed Ali, and he obsessed about a re-match. He pestered his manager about another fight, and embarrassed himself by confronting Ali at a public photo shoot. To prove his worth, he staged an exhibition match against five successive men in one evening – a performance which Ali heckled from ringside.

It seemed desperate. It was desperate. The great George Foreman had lost the mental battle. It was unthinkable that he could become world heavyweight champ again.

*

In 1977, George Foreman – while obsessively making his way to a rematch with Ali – fought Jimmy Young. He lost. Foreman was 28, and in the locker room after the fight he stripped himself naked and began ranting deliriously about death and Jesus. He was eventually pinned to a table by several men, then hospitalised.

George Foreman would later say that he had seen God and smelt death. Doctors thought severe dehydration, a rattled brain and adrenalised nervous system had contributed to some kind of breakdown.

Either way, George Foreman was done. He quit boxing, and found the Lord. He shaved his head, his beard, and committed himself to public works. He spoke at local churches, and helped build a local youth rec centre. He lost his desire for boxing.

And so, when Foreman returned to the ring one decade later, in 1987 – slow and doughy and physically unrecognisable from his peak – most assumed it to be an insincere grab for money. Part of that was true, at least. Foreman needed money.

A comeback seemed absurd. Foreman was fat, and made good fun of his own weight and love of cheeseburgers. There were successive wins against poor opponents, though few thought they mattered. But Foreman had excited promoters. The old heavyweight champ would meet the current champ, Evander Holyfield.

It was a good fight and a noble loss. The old man was defeated on points, but had surprised most, and secured a purse for the youth centre back home. But by now, George Foreman had secured a sufficient hold on American popular culture – his transformation into an affable and self-effacing priest had given him a short-lived sit-com bearing his name – and fight promoters clamoured for him.

So when the belt for the heavyweight was transferred from Holyfield to Michael Moorer, promoters salivated at the prospect of a Foreman fight. The quality now of the heavyweight class was vastly diminished – Mike Tyson was in jail, and public interest had greatly eroded since Zaire – and Foreman’s inclusion was assumed to create interest.

And so it did. It was November 5, 1994. George Foreman was then 45 years old, and had not held the world heavyweight title since he lost it to Ali 21 years before. Michael Moorer was 26.

In the fight, Foreman was everything he wasn’t in Zaire: slow and patient. He took punches and waited. He knew that he’d never take the fight on points. He’d have to knock him out. And then he took some more punches, and waited some more. Foreman could wait now. God and time had taught him this.

And then, in the tenth round, George Foreman saw his window and knocked Moorer out. At 45, he reclaimed the title he lost in Zaire and became, by far, the oldest heavyweight champion ever.

It’s a great professional arc, and one expensively transformed into a feature film only a few years ago, but Foreman’s life has rarely been treated as anything other than a dramatically exploitable tale of unlikely redemption.

Which it was. The brutal fighter who was mortally embarrassed, and then fell into a pit of repellent self-pity, emerged as a famously affable icon – and then an unlikely reclaimer of his lost title.

Foreman became a preacher, brief sit-com star and brand genius – an all-American pitchman – and he earnt more from promoting his smokeless grill than he ever did in the ring.

A happy man, and serene, who could reclaim his brutal gifts without the murderous intent and then attribute his fortunes to the Lord. But then I read his 1995 memoir, released after his reclaiming the heavyweight title, and he was still bitterly relitigating 1974: his water was drugged, the referee was dodgy, and Ali’s “rope-a-dope” was not a pre-arranged tactic, but a desperate improvisation.

The holy transfiguration of George was not, I thought, ever completed other in the minds of journalists. But that’s now a matter for his Lord.