A few weeks ago, I finished the first draft of my third book, an untitled collection of portraits of three former emergency workers – a paramedic, a copper and a firie. Two of the three suffer from severe and treatment-resistant forms of PTSD. The third has never been diagnosed, but she attributes her firefighting career to ambitions born from a significant childhood trauma – one that would be jarringly echoed by some of the jobs she was called to.

To finish a good book requires some powers of will, concentration and imaginative sympathy – virtues I’d once vainly assumed to possess abundantly, but which I now understand to be preciously finite and possibly in terminal decline. Such work, if it’s to be done well, also requires a fortified ego and unnatural reserves of energy: the former to mitigate against the erosions of doubt; the latter to better steel you while immersed in stories of awesome depravity.

Such an internal balance – of ego, energy and sympathy – becomes harder to maintain as you age, and the limitations of your abilities become more apparent. It is also difficult to maintain against the intrusions of PTSD, for I, some years into this book, would be diagnosed with the same damn condition I was writing about.

It was humbling, to say the least, to finally recognise my own long resistance to the facts of my health. But naturally it became harder to ignore my own symptoms as I saw them in those I was writing about, and my resistance softened. At first, it graduated from wilful obliviousness to a form of qualified acceptance: sure, I possessed comparable symptoms, but it wasn’t all that bad and surely would only improve.

It was only when I developed physical twitches and rolling panic attacks – the latter so severe that I routinely misinterpreted them as heart attacks and took to loitering around the nearest GP clinic so that I might be close to medical assistance – that I slowly came round to asking for help.

Exhaustion is perhaps the most prosaic element of PTSD, but the one that most irritated me – it seemed the worst bully of my work and ambitions. To begin with, there are the nights disrupted by nightmares and wet sheets and the corresponding days spent in the mental grime of sleep-deprivation.

But there’s another instrument of exhaustion. When the mind is hyper-vigilant and inclined to trigger massive floods of cortisol on a near-daily basis and according to the flimsiest pretext – a popped balloon, a dropped plate – then one is constantly living either in a state of adrenalised arousal, or, worse, suffering from the hangover left by the hormones’ departure. The tide will retreat, and you’ll be left beached and exhausted upon a shore of pebbles.

*

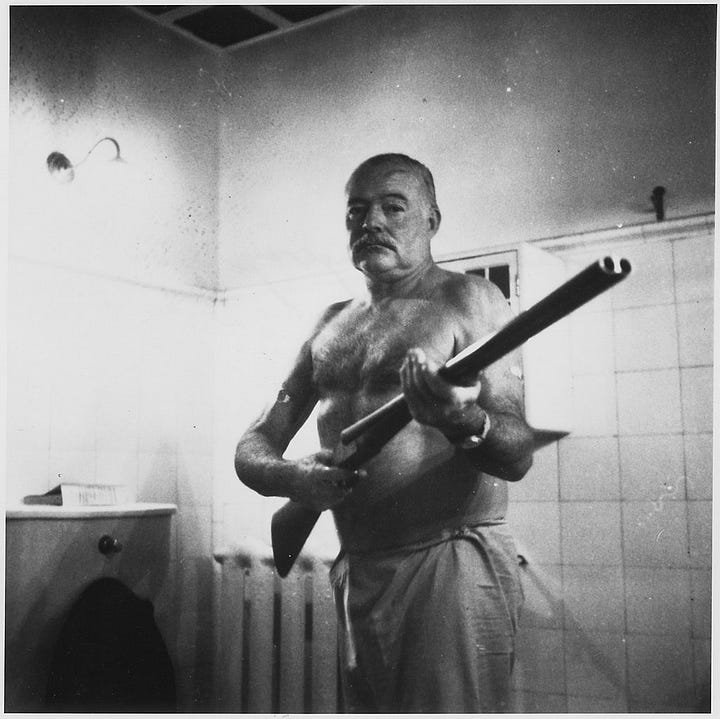

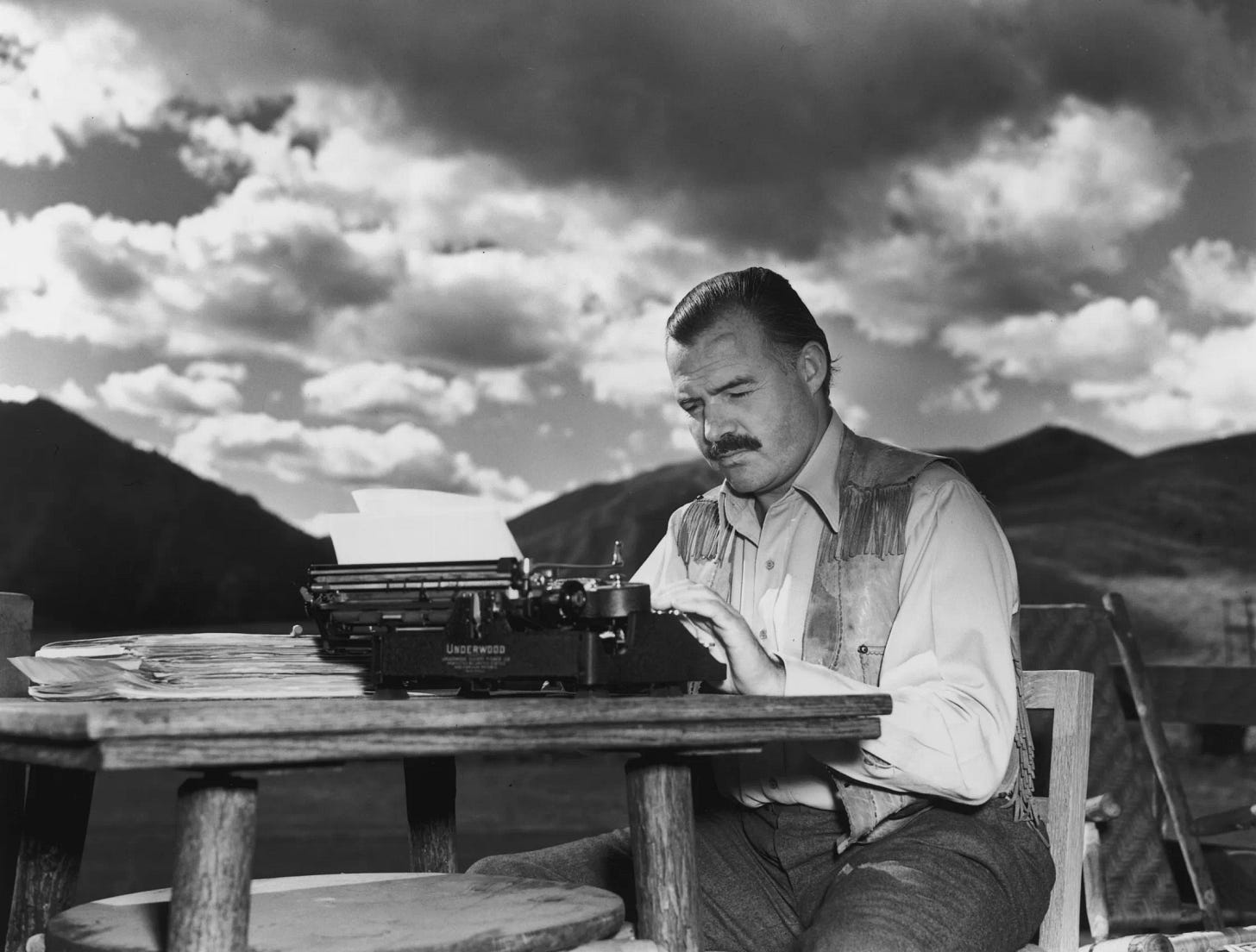

With Peter, the paramedic, we spoke for perhaps a year before I began writing. As I did, I thought of Ernest Hemingway and his time as a Red Cross ambulance driver in World War I. None of this made its way into the book, but I think of it still – not merely the facts of Hemingway’s experience, but his intolerance of psycho-biographers searching for meaning in it. “You do not like to be tailed, investigated, queried about, by any amateur detective no matter how scholarly or how straight,” Hemingway wrote to a prospective biographer, the scholar Charles A. Fenton, in 1952, in what would be the first of several attempts to dissuade him from his work.

Hemingway was only 18 and had barely arrived in Italy, in 1918, when an explosion at a munitions factory just outside Milan obliged his attendance and transferral of dozens of body parts. “In the barbed wire fence enclosing the grounds and 300 yards from the factory were hung pieces of meat, chunks of heads, arms, legs, backs, hair and whole torsos,” Hemingway’s partner that day, Milford Baker, would later write in his diary. “We grabbed a stretcher and started to pick up the fragments. The first we saw was the body of a woman, legs gone, head gone, intestines strung out. Hemmie and I nearly passed out cold but gritted our teeth and laid the thing on the stretcher.”

Only weeks later, Hemingway’s legs were shredded in a mortar blast and he recovered in a Milanese hospital – an episode later transformed into one of the Nick Adams’ short stories, 1927’s “In Another Country”. “In the fall the war was always there, but we did not go to it anymore,” it opens.

In 1952, the scholar Philip Young published a revised version of his PhD thesis on Hemingway’s work, which Hemingway initially and energetically sought to prevent. I first read the book in 2003, when I found a second-hand copy in an antique store in Seoul – one not very far away from the city’s major US military base, as it was. It remains the best thing I’ve ever read on Hemingway, a lively, well-written examination of his work and prosecution of a basic case: that much of his work, not least the string of early, exceptional short stories, were about fear and its overcoming, stories derived from his original “wounds” of 1918.

But Young went further. Hemingway was obsessed with danger, impulsively rushed towards it, and in doing so accumulated catastrophic mental and physical injuries – he had volunteered for too many crucibles and scorched his nervous system in the process. (He was also, oddly for a man who had courageously distinguished himself in various ways, an inveterate liar and exaggerator of stories regarding his physical heroism.)

As it was, Hemingway despised the intrusions and theories of scholars, none more so than those bearing Freudian analysis. In his foreword, Young tells us that his reluctant, increasingly indignant subject wrote to him: “To tell a writer he has a neurosis, Hemingway did write me, is as bad as telling him he has cancer: you can put a writer permanently out of business this way.”

In 1954, the year he won the Nobel Prize, Hemingway told Time magazine: “How would you like it if someone said that everything you’ve done in your life was done because of some trauma? I don’t want to go down as the Legs Diamond of Letters.”

Diamond was a Prohibition-era bootlegger who survived several assassination attempts and whose body was filled with the proof. Hemingway did not want to be thought of merely as some plucky survivor, nor a sad captive to his so-called “traumas”.

*

The English writer J.G. Ballard led a much less crowded life. In fact, it was a determinedly domestic one, and when Ballard became widowed very suddenly at the age of 34, he refused the offers of his wife’s family to assume custody of his young children and became a rare thing in 1960s England: a single father.

But I thought of Ballard’s own reluctance – or at least casual dismissal – of the influence of his own childhood wounds upon his adult work and imagination. As a child, Ballard, along with his family, was a Japanese prisoner of war in Shanghai. Overnight, his family went from being prosperous to being prisoners, and he absorbed then a large lesson about the instability of seemingly stable things.

But what struck me as I read his memoirs is how late his recognition came that the experience of Shanghai had been informing his fiction all along. It was not, he wrote, until his 1984 publication of his most famous novel, Empire of the Sun – one which explicitly takes as its subject his childhood experience – that he came to see how “the memories of Shanghai that I had tried to repress had been knocking at the floorboards under my feet, and had slipped quietly into my fiction”.

As I wrote a few years ago:

The experience was profound, though it took him decades to realise that his novels might all be forms of sublimating it. He stubbornly resisted suggestions that his florid imagination and recurring metaphors might all derive from his unsettled childhood. I’ve often wondered if this resistance was the pride of the artist who doesn’t want the origins of his imagination made obvious, if he preferred its mystification to its being attributed to “mere” metaphorical re-orderings of his childhood. Let me put it another way: I wonder if Ballard ever really thought that his imagination was truly free from his past.

*

I like to think that both Hemingway and Ballard retained a certain pride, however deluded at times, in the near-mystical protean energies of their imaginations – that it was phenomena not merely or basely attributable to their “early wounds”, but a larger and more splendidly mysterious thing. In different ways – Hemingway more militantly and paranoically patrolled the borders of his public reputation – both men, I think, refused to reduce the expressions of their imagination to some singular neurosis.

This stubbornness, however vain or deluded, compares flatteringly with the newer fashion of finding pride in one’s trauma and diagnoses. To find pride and personal definition in illness seems like another sickness to me, while the insistence upon the mysterious independence – however much I quibble with it – still seems like a valiant and useful deception in so far as it accepts the multitudes that comprise each of us.

As it is, the mental health of Hemingway only worsened, and Young’s book found sharper light after his subject’s suicide in 1961. In 1954, Hemingway experienced two consecutive plane crashes. In the first, in the Belgian Congo, his small aircraft clipped a telegraph wire and went down. His liver and kidney were ruptured, his lower spine crushed, his skull smashed open. His anus leaked, he saw double for a time, and he suffered temporary hearing loss. Almost implausibly, the rescue flight crashed too and the aircraft ignited on impact. Hemingway was severely burnt.

Months later, having received the Nobel – which he was not well enough to accept in person – Hemingway gave a sad, peculiar interview to CBS news, in which he relied upon cue cards for his answers. What you can see in this clip is obvious brain damage.

*

It’s hard these days to accept Hemingway as a model for much. The man became terribly “truculent and childish” in the words of his final wife, and bitter and paranoid in the words of others, and for many years before his death he wrote in a funk of sickly self-parody. Hemingway never had “the versatility to run away fast enough from his imitators,” the great critic Cyril Connolly wrote in 1938’s Enemies of Promise. “A Picasso would have done something different; Hemingway could only indulge in invective against his critics – and do it again.”

I think this is true. But never mind his inability for creative adaption: by the end, he could not even manage the two sentences that president-elect John F. Kennedy had requested for his inaugural address. Once artistically limited, Hemingway was now very, very sick.

In a Chicago blizzard in 2009, against the backdrop of similar thoughts, I walked between the Hemingway Museum in Oak Park and his childhood home a few blocks away. I’d taken the wrong train, and thus endured a much longer walk to the museum than was necessary, and taking sympathy upon an Australian who’d surprisingly arrived in a snowstorm at this otherwise empty museum, the staff there called ahead to the home to tell them not to close for the day because a young man was on his way.

Of 339 North Oak Park Avenue I recall very little, other than the sense that the man who let me in was the proud custodian of an American myth and unlikely to indulge my more complicated views of the man that I’d first encountered, aged 21, in the short story “A Clean Well-Lighted Place”.

That story was a revelation to me. In that piece, and the others I read in the collection The First 49 Stories, I found subtle stories of fear and trauma expressed with a musical plainness and made resonant by skilfully withheld information. The deep, melancholic suggestiveness of these stories reminded me then of how I received the occasional stories and whispered interpretations of my grandfather’s time as a Japanese prisoner in Changi – the spooky sum of things unsaid or unknown.

Later, I would come to find Hemingway excessively mannered and agree with the late critic Dwight MacDonald that the intensity of his austerity was always better suited to the short story. “It is curious how verbose Hemingway’s laconic style can become,” MacDonald wrote in 1962, and about his novels it’s true.

But I said none of this in Hemingway’s birth home, not to the man who was so hospitably guiding me around his shrine, and afterwards we said goodbye and I returned to the blizzard outside, unsure about what, if anything, I’d learnt by peering into these long empty rooms.

Today – as I write this – I can see some things. One is my easy refusal to feel either shame or pride in a diagnosis. The second is seeing that my rejection of Hemingway was too severe, and that there are still lessons to be found in the early work, despite his lies and puerile machismo and eventual surrender to self-parody.

The third is seeing that my book’s three exceptionally candid and bruised subjects each share something with Hemingway: an early, uneasy sense of inadequacy that was corrected by their assumption of public service and great risk. They ran into danger compulsively, to save others but also themselves. And it worked, until it didn’t.

Very nice take on Hemingway, and very similar to my own. (I was of course a Hemingway tragic for most of my twenties, visiting all the usual stops in Cuba, as well as the grave in Idaho. I'm still an fan of the bullfight because of him.) I think you fall out of love by the time you get around to ACROSS THE RIVER AND INTO THE TREES, which is woeful, if not FOR WHOM THE BELL TOLLS, which is at times very good but mostly turgid. But you wouldn't hand back the stories or the first two novels. Did you see the Ken Burns documentary, out of interest?