On June 21, 1995, God was recovering in a hospital bed. The surgical thinning of his “jowls” had been successful. “I’ve lost so much weight that they began to look inflamed and were totally unaesthetic,” Diego Maradona said through a translator.

Only a year before, El Diego had tested positive at the ’94 World Cup for several outlawed stimulants and banned from the game for 15 months. His exile was close to ending that day, but he couldn’t know that he’d already played his final game for Argentina.

Over the years, there would be further submissions to cosmetic surgeons, as Maradona’s face was variously stretched, cut and plasticised. But it was all the other hospital admissions, to emergency departments and psych wards, that captivated the country in which he was venerated as a demigod.

In 2000, when El Diego almost fatally overdosed on cocaine, he found in Fidel Castro an indulgent patron. The Cuban president invited Maradona to a rehab clinic in Havana, where he lived for almost four years and enjoyed almost as hedonistic a lifestyle as he had in Buenos Aires – a life of steak and champagne; sycophants and nightclubs.

Four years later, when an obese Maradona was admitted to an Argentinian intensive care ward suffering an inflamed heart and faltering lungs, his family announced his decision to return to Cuba for further treatment for his cocaine addiction. This time, an Argentinian judge applied conditions to his Cuban stay: he would be confined to the clinic, and denied the lavish privileges he’d previously enjoyed. This time, his family hoped, Castro might serve as a “strict father” – the implication being that El Diego had earlier been indulged, destructively, as a Cuban mascot.

From that day in the hospital bed thirty years ago, the great Maradona had played his last match for his country and only 30 more club games would follow for his beloved Boca Juniors.

Until his death five years ago, aged 60, Maradona’s weight fluctuated dramatically; so too his lucidity. Still, he was adored, indulged, anointed. Without any managerial experience, he was made senior coach of Argentina in 2008; his brief 2005 talk show – where he riffed with Robbie Williams about coke, and celebrated Che Guevara with Fidel Castro – was appointment viewing for Argentinians.

Maradona’s friend, and English translator of his biography, Marcela Mora y Araujo, described the series as chaotic, and one in which Maradona did most of the talking – “often directly addressing his parents in the studio audience as well as speaking of his desire to be reunited with [his ex-wife] Claudia.”

And it was wildly popular. Normal rules didn’t apply to Maradona. They never did. How could they to a man who found the veneration of a country, and never lost it despite becoming a bloated caricature of excess and babbling self-pity? A man who found the patronage of priests, Fidel Castro and the Neapolitan mafia?

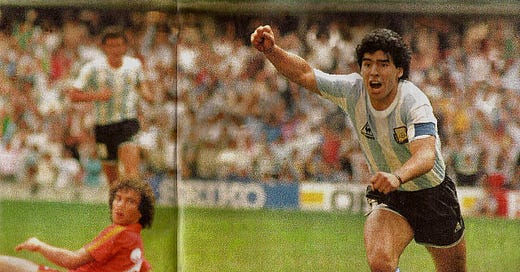

No, normal rules never applied to El Diego – he could bend them with genius or he could bend them with contempt, and his two goals against England in the 1986 World Cup are neat proof of both. In that same game, he beat an imperial power first with a deceptive fist and then with “The Goal of the Century”.

It pleased Maradona, as it pleased his country, to think of beating Thatcher’s England – victors, only four years earlier, of the Falklands War – with both slum grift and sublime skill. Maradona had, he said, secured Argentina’s “symbolic revenge” for the war.

But as much as Maradona occupied his own special jurisdiction, a kingdom in which his genius was indulged just as well as his immaturity, the rules of his own biology could never abide his exceptionalism.

His heart, lungs and mind were only occasionally dependable. They’d all been heroically abused, and were now suffering the consequences. “I don’t really feel that I am God,” El Diego admitted in 2008. “There is one God and it’s not me. [But] People have faith in me, they believe in me as perhaps they believe in God, and I’m not going to contradict them.”

But his body eventually did. It couldn’t help it.

*

On June 21, 1995, the National Basketball Association fined the Chicago Bulls $100,000 for allowing Michael Jordan, newly returned from his retirement, his unauthorised reversion to his old #23 jersey number in the middle of a playoff series the month before.

This might seem like an oddly trivial example of the NBA’s officiousness, but it spoke to the grief and superstition of one of history’s greatest athletes.

Two years earlier, Jordan’s father, James, had been driving between Wilmington and Charlotte, North Carolina, after attending a funeral that day. It was a long drive, and it was late, and halfway through the trip decided to rest. He parked his red Lexus, a gift from his son, in a highway rest area and slept.

Eleven days later, a severely decomposed body was found in a South Carolina swamp. It was then cremated by the state coroner as a “John Doe”. Another eleven days would pass before dental records confirmed the body was James Jordan. He had been robbed, then fatally shot, by two teenagers in the rest area – and his corpse moved interstate and dumped in murky waters.

Michael Jordan bought handguns for self-defence; he began anxiously checking his rear-view mirror for people following him. Then, in October 1993, Jordan announced his retirement from basketball. He said he’d lost his motivation and, having won three consecutive championships with the Bulls – and three league MVPs – that he had nothing left to prove. “I love the game of basketball,” he said. “I always will. I just feel that, at this particular time in my career, I have reached the pinnacle.”

Years before, Jordan had discussed with his father becoming like Bo Jackson – the freakish athlete who had distinguished himself in both football and baseball. Jordan loved baseball, but hadn’t played the game since he was a teenager, and inspired by his late father’s faith he left his throne upon basketball’s summit for the toil of baseball’s minor leagues.

Jordan played for the Birmingham Barons, a Double-A minor league team associated with the Chicago White Sox, and he struggled. On debut, he struck out five times from seven hits. “It’s been embarrassing, it’s been frustrating, it can make you mad,” he said at the time. “I don’t remember the last time I had all those feelings at once.”

Eddie Einhorn, a White Sox executive, wondered if Jordan wasn’t performing “penance” for his father – trying to find some personal abasement or suffering to better commune with him. “Seems to be true, doesn’t it?” Jordan told the New York Times of Einhorn’s theory. “I mean, I have been suffering with the way I’ve been hitting – or not hitting. But I don’t really want to subject myself to suffering. I can’t see putting myself through suffering. I’d like to think I’m a strong enough person to deal with the consequences and the realities. That’s not my personality. If I could do that – the suffering – to get my father back, I’d do it. But there’s no way.”

But in 127 games for the Barons, Jordan improved – not enough to make the Majors, but enough that his surprising shift to baseball wasn’t the clownish experiment it’s often remembered as.

But something else improved, too: Jordan’s motivation for basketball. In March 1995, Jordan declared his intention to return to the Bulls with a famously short press release: “I’m back.”

When Michael Jordan returned to the NBA, he did so by incongruously wearing the number 45. It was jarring. By now, Jordan had ascended to the most rarefied heights of fame and the #23 was synonymous with his global idolatry and branding. But Jordan had his reason: “Twenty-three was the number my father last saw me in, and I wanted to keep it that way for him.”

He would wear the number 45 for only 22 games. The last time he did was Game 1 of the Eastern Conference semi-finals against the Orlando Magic. Jordan led the Bulls for scoring in that game, but with wasteful inaccuracy, and in the game’s final ten seconds he lost the ball twice – costing his team victory.

Here was the humiliation and struggle he’d experienced in baseball. But it was a more bracing experience in his native game, the one in which he had always sought, with merciless ferocity, to dominate and embarrass his opponents. Victory was never enough for Jordan; he wanted the vanquished humiliated. He wanted psychic blood. He wanted his supremacy to echo round stadiums, to spook opponents’ dreams, to be committed to history books. And now he’d been humbled himself.

“Number 45 is not number 23,” the Magic’s Nick Anderson said after the game.

And so, Jordan retired the number 45. It wasn’t only in the minds of fans that the #23 had become special, synonymous, irreplaceable. Jordan came to think of it the same way, as something elemental and true, and shedding the new number for the old gave him an act of symbolic rejuvenation. “If it’s a mental confidence, then it’s a mental confidence, and I think it has been,” Jordan said of his decision to abandon #45. “I’m going to stick with it until I finish playing basketball. That’s me. Twenty-three is me. So why try to be something else, even though I know my father has never seen me in 45. It was a choice I chose to make.”

One he chose to make, but one the Bulls failed to seek permission from the league for. Thirty years ago, the league fined the team $25,000 for each time Jordan wore the unauthorised number. The Magic beat the Bulls in six games, but from the next year, Jordan led them to another three consecutive championships.

He’d recovered his motivation. And Hollywood was glad. On June 21, 1995, as the NBA declared their fine, Warner Brothers announced that Jordan would be paired with Bugs Bunny in a film scheduled for release in late 1996. The studio could bank upon Jordan’s fame, as they could his bloodless commitment, and in time Space Jam became a decent profit maker.

There was no chance, of course, that Hollywood would ever bank similarly upon Maradona – his genius was too foreign, his energy too anarchic, the prospective market too indifferent. But on that day, June 21, 1995, the sublime gifts of Michael Jordan were, once again, being spun into intellectual property on Madison Avenue and in Beverly Hills. And in Buenos Aires, before their portraits of El Diego and Pope John Paul II, the people prayed for the speedy recovery of their God’s chin.