Mailer & Muhammad

50 years since "The Fight"

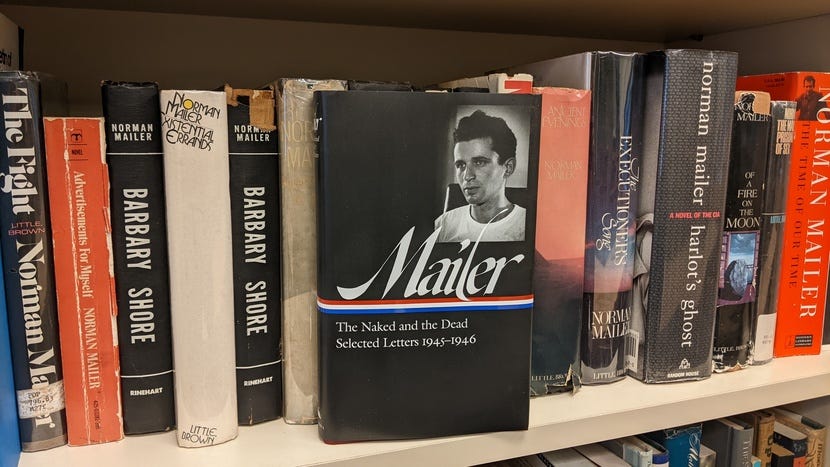

Fame came early for Norman Mailer, and it did funny things to him. He was just 25 years old when, in 1948, his novel The Naked and the Dead – a fictionalised account of his time fighting in the Pacific as a United States rifleman – became a phenomenal bestseller.

Mailer’s ego was both excited and made tremulous by his extraordinary success. Initially timorous about literary fame and its expectations, Mailer leant heavily into pot, existentialism and his mother’s sickly affirmations – and from there, he developed a grandiosity that was both a public relations exercise and an intimate attempt to convince himself he was both a better writer and braver man than he privately thought he was.

In the late 1950s, and not yet out of his 30s, he declared his ambition to be no less than writing a book that would cause “a revolution in the consciousness of our time”. His grandiosity, even more than his work, became famous and easily parodied. It also became progressively unattractive, not merely by his philosophical faith in violence and machismo but also by his humourlessness. Wit always escaped him.

Still, 50 years ago, Mailer gave us one of the best sports books I know of – one as memorable for its flaws as its virtuosity.

*

Beneath American public life, Mailer wrote in 1960, “[T]here is a subterranean river of untapped, ferocious, lonely and romantic desires, that concentration of ecstasy and violence which is the dream life of the nation.”

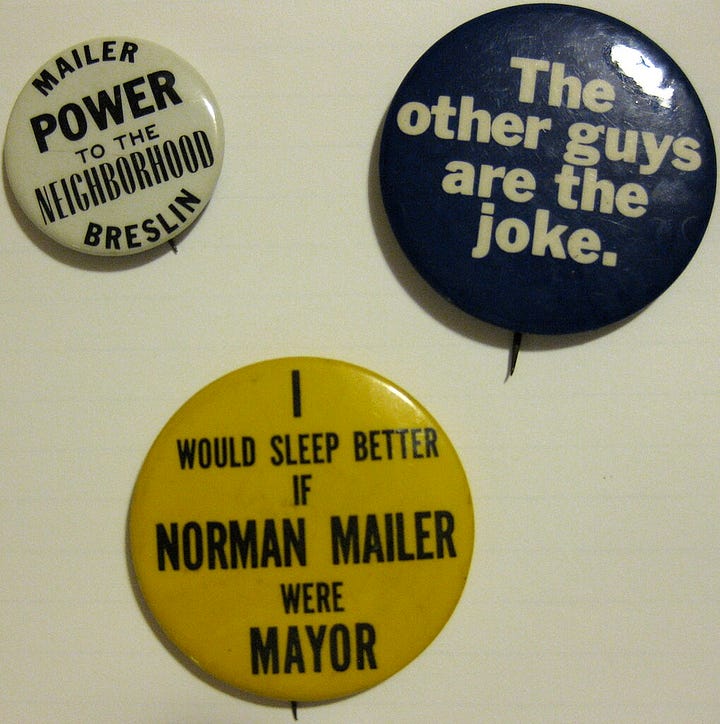

Mailer was the Huck Finn of that river, and its psychotic churn in the late 1960s and early ’70s offered perfect rafting conditions for a weird adventurer. He marched on the Pentagon in ’67 and was arrested; the next year he walked the streets of Chicago with hippies, Yippies and the cops empowered to crack their skulls. Mailer would wander to wherever duelling American dreams confronted each other.

Ultimately, I think, Mailer was a Jungian mystic and spoilt mama’s boy who thought the true nature of the cosmos was a crowd of psychic archetypes arrayed beneath an inscrutably mischievous God – and who saw his own role as a kind of drunk Moses appointed to share His revelation.

But Mailer’s mysticism wasn’t metaphorical or exaggerated. He literally believed in good and evil as divine forces. He believed in karma and reincarnation. He believed sex and violence could be sites of cosmic epiphany. He was a man who lurched between prophet and crank; someone who could embarrass himself with nutty theories just as easily as he could redeem himself with insight.

He had little interest in proportionality or good taste. He couldn’t care less about weighing the risks of any work to his reputation. What he had in mind was nothing less than cracking open the true nature of the universe with some thunderous revelation – and he risked, and found, great embarrassment in doing so.

He could be loutish and piggish. His sexual politics were aggressively reactionary. He brawled in bars, in streets and on national television. When his cartoonish grandiosity was mocked during public speeches, he could turn sour with fury. For a time, the angry ambition of Norman Mailer became a fact of American public life, much like the duplicity of Richard Nixon or the self-dramatising neurosis of Woody Allen.

And he could be much worse than loutish. At a party in his Manhattan apartment in 1960, Mailer – after a night of heavy drinking and bad vibes – twice stabbed his wife, Adele. One entry of his penknife was to her chest and it only narrowly missed her heart. The seer of national psychosis was psychotic himself, and he was soon institutionalised.

*

I’ll share something else before I get to the sport – before I get to Muhammad Ali. Norman Mailer hated plastic. Really hated it. This “excrement of oil” was “the spiritual equivalent of political correctness”, he once said, and he was disturbed by the thought that babies’ toys were made from the stuff, thus introducing us all to its spiritually malign effects almost from day nought.

It was worse than this, though. Mailer thought plastic caused cancer, and not in the obvious way – not through physical sickening – but through mystical corruptions. It deadens people, Mailer said, by divorcing them from tactile pleasures and the natural materials of the earth. It was all part of modernity’s air-conditioning of the soul.

In 1965, when Mailer began building a two-metre-tall model of Mile High City, his concept for a “vertical city of the future more than a half mile high” he did so with Lego blocks, which are made, of course, from the odious excrement. But the material spooked him and he thought the sound of the blocks snapping together was “obscene”, and so he mostly had friends assemble the colossal project under his direction.

In what might serve as a neat metaphor for Mailer’s messy ego, when a museum showed interest in taking custody of the model some years later, it proved too large to be removed from his Brooklyn home without disassembling – something Mailer refused on account of his fear that it could not be remade exactly as it was.

Still, Mailer’s ego was a decent instrument for evaluating Muhammad Ali’s – and the trials and consequences of possessing it. Professional fighters were the opposite of plastic – he saw in them the transfiguration of flesh, sorrow, anxiety. In describing the psychic tolls of public performance, and finding in them echoes of ancient myths, Mailer tried to vanquish our glibness.

*

The famous Rumble in the Jungle fight of 1974, between Ali and world heavyweight champion George Foreman, was hosted by Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and its notorious kleptocrat, President Mobutu, who was then busy replacing colonial occupation with a brutal cult of personality.

The outsized Ali and the sleazy world of heavyweight boxing – now transplanted to the Congo’s “heart of darkness” – was an ideal subject for Mailer. From the opening paragraph, you realise you’re in the hands of a master even if you never know when Mailer will eventually get stuck in a strange bog of mysticism:

“There is always a shock in seeing him again. Not live as in television but standing before you, looking his best. Then the World’s Greatest Athlete is in danger of being our most beautiful man, and the vocabulary of Camp is doomed to appear. Women draw an audible breath. Men look down. They are reminded again of their lack of worth. If Ali never opened his mouth to quiver the jellies of public opinion, he would still inspire love and hate. For he is the Prince of Heaven – so says the silence around his body when he is luminous.”

An amateur boxer himself (Mailer exchanged writing lessons for boxing ones with the former world light heavyweight champion José Torres), Mailer noticed small, technical things: “No punch disturbs the shoulder more than the one that does not connect – professionals can be separated from amateurs by the speed with which their torso absorbs that instant’s loss of balance.”

But what both made and imperilled the book was the spiritual frame Mailer imposed upon it. Before leaving New York for Zaire, he read a book written by a Dutch missionary assigned to the Belgian Congo about the tribe he lived among. “Given a few of his own ideas, Norman’s excitement was not small as he read Bantu Philosophy,” he wrote. “For he discovered that the instinctive philosophy of African tribesmen happened to be close to his own. Bantu philosophy, he soon learned, saw humans as forces, not beings. Without putting it into words, he had always believed that … A man was not only himself but the karma of all the generations past that still lived in him, not only as a human with his own psyche but a part of the resonance, sympathetic or unsympathetic, of every root and thing (and witch) about him.”

Mailer respected Foreman’s strength and sophistication as a fighter just as he respected his cloak of silence – “an ocean” of antisocial concentration with which to defend himself against a country hostile to his prospects. But he was besotted with Ali, to whom much of the book is devoted and whom Mailer thought of as a quasi-religious figure.

This being Mailer – both an idiosyncratic mystic and recurring character of his own journalism – he becomes oddly superstitious about his own influence on the outcome of the fight. It’s a peculiar magical thinking, inflected by his reading Bantu Philosophy, that compels Mailer to drunkenly cross the partition between two adjoining and high-rise balconies of his hotel. This absurd risk, he believes, might better feed Ali’s “magical equation”.

If this seems bizarre and distracting, you’re right, but Mailer also confesses to being disgusted by his eccentric vanity. One doesn’t read the guy for neatly sterilised accounts of history but, rather, for how his own psychic humidity mixes with its subject.

Mailer’s description of the fighters’ training sessions are excellent and his account of the fight itself unmatched. They’re dramatic and precise and lifted by rarely good metaphors (having exhausted himself, Foreman was as “slow as a man walking up a hill of pillows”).

While the drama and specific mechanics of the fight are brilliantly relayed, it’s the meaning of Ali’s surprising triumph that most electrifies Mailer – loaded, as it is, with personal inspiration: Ali had found a way to beat a stronger fighter by renouncing his old virtuosity and replacing it with the ability to withstand deep punishment.

For Mailer, when Ali sprung off the ropes and felled his exhausted opponent, guile and reinvention had beaten prodigious strength.

Had I ever spoken with Norman Mailer, who died in 2007, I would have asked him about the meaning of the success of The Executioner’s Song – his 1979 book about the killer Gary Gilmore, who did not care to appeal his death sentence and thus awoke a circus of legality and media interest.

I’m not alone in thinking it Mailer’s best book, but the curious thing is that this great artistic and journalistic success is also stylistically unrecognisable. For a man who’d sought to deliver revelations in thick and feverish paragraphs – not unlike his hero D.H. Lawrence – here was a book that, if delivered to you upon publication without its cover, you would never have guessed its author. The Executioner’s Song is written with astonishing plainness.

What was the personal significance of this – that perhaps his greatest book is the one with the least conspicuous imprint of his ego, style and half-mad vivacity? And, if I were feeling bold, I would have then asked: what lessons did he take from Ali in ’74, when he won the fight through guileful renunciation? Through a painful abandonment of style?

For all of Mailer’s madness, he was at least prepared to gamble on his talent for an artistic vision – and not merely to fund his extensive alimony payments when the “glossies” still mattered and could pay extravagantly. Distant times for most, or just plain forgotten.