Last year, I reviewed Meet Me in the Bathroom, the documentary adaptation of Lizzy Goodman’s large, digressive, and often juicy oral history of New York City’s indie rock scene of the noughties. Her book, published in 2017, took seven years to make, and contained hundreds of interviewed subjects, including the major figures of the time: The Strokes, Interpol, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, TV on the Radio, LCD Soundsystem and Mouldy Peaches, amongst others. The book became a bestseller.

I saw the film as part of last year’s Melbourne International Film Festival, but it has just now been generally released to cinemas in Australia. The film is refreshingly free from talking heads — instead, it’s entirely comprised of archival footage, most of it previously unseen. As such, the film is modest, grainy, intimate. It captures naïve kids before their being shot into fame; as it captures their variously giddy, exhausted and frightened faces within the eye of the storm. Most of all, the film strives not for bibliographic detail, but for capturing something of the feeling of the time. It’s a collage of scraps, the sum of which is hoped to be greater than its parts.

“When [directors] Will and Dylan came to me with the idea of making a documentary based on the book, the thing that made me feel good about them as directors for that project was a vision that included a sense of emotional truth, rather than literal truth, which is, honestly, also how I felt about making the book,” Goodman told me earlier this month. “I think you can have a kind of Wikipedia-style, outline-slash-timeline of events, and a lot of music books are written that way, where it’s just sort of like: here’s what happened. And honestly, I’ve enjoyed a lot of those. It’s just that when I had the idea of trying to get this period of time down on paper in some way, it was just clear from the jump that it required a form of storytelling that would circumvent these kinds of bibliography-style renderings, and it would require something that had less obsession with fact and more obsession with feeling, and that’s what oral history allows you to do.”

Goodman’s book was sub-titled Rebirth and Rock and Roll in New York City 2001–2011, but September 11 exists in the film only subtly — it casts a shadow mostly through suggestion, or from us filling the gaps. I asked Goodman an impossible question: if the scene, or the music, might’ve been different if that day had never happened. “That America and its crown jewel city could be attacked in this way, and can be ripped open in this way, was scary and it certainly returned us to a sense of wanting to be connected to the most basic things in life,” Goodman says. “You wanted to hear loud music, you want it to be connected to a sense of sexuality, you want it to be connected to primal energy, which rock and roll is the sort of ultimate offering for.

“No one who’s 21, who’s like super insecure and ambitious and maybe prone to addiction is going to have a really reasoned response to this national trauma we’re living through. What you do is you go, ‘Oh, I’m going to chase all of my addictions even harder. I’m gonna chase my desire to be famous, or my desire to make great music, or whatever that is — I’m going to double-down on that.”

The film’s house-band is The Strokes, who Goodman got to know in those early days, and of whom the book was initially entirely devoted. Before fame, they were already bratty and rich, and I recall at the time some lifted eyebrows about privileged kids cosplaying as grimy garage rockers (which to be fair, could be said of many of their forebears). But mostly, they received rapturous critical praise as music’s defibrillators.

And what the film got me thinking last year, and what I would ask Goodman about recently, was how, at the turn of the century, The Strokes were celebrated in a way that might no longer exist: as our saviours from sterilised “corporate rock”. Perhaps even more so than their music, its reception is a distinctive moment in time.

*

In my early twenties, at the start of the new century, I was a cultural warrior. Scrawny, greasy-haired and affectedly swaggering, my uniform was purchased from op-shops: frayed t-shirts and corduroy flares. I wrote imitative trash on a $10 typewriter, and was passionately convinced that the earth was drowning in mediocrity and complacency. This “fact” was best proved by popular music, which I felt was soulless and narcotising, and while my pleasure in indie music was electrically real, a secondary pleasure was thinking myself special for enjoying it.

Despite my callowness — or, actually, because of it — I diagnosed people with severe intellectual and moral failings because of their music taste or, worse, their indifference to music. Popular nightclubs were vulgar markets, and our lone indie club was a soulful church. I had no problem mouthing off to bouncers, who I saw as thuggish guardians of evil gardens, and had little hesitation in expressing my irritation with people who hadn’t heard of Sparklehorse.

Obnoxious, obviously, and I wasn’t sufficiently wise or self-aware to realise that this was all grounded in 1) exaggerated misanthropy, 2) a misanthropy that pleasurably sustained belief in my own superiority, and 3) a profound lack of perspective. To this, you might add a curiously strong belief in the quantification of “good music” and my indifference to the pleasure that people felt while listening to “bad music”.

But there you are. That’s how it was. That’s how I was. Besides the immediate pleasure, music provided a community, fed personal identity, and offered the sense that you were a nobly engaged guerrilla within a cosmic struggle between good and evil — i.e. artistic purity and corporate appropriation.

As a geriatric millennial, I only caught the end of this thinking, which was probably most intense in the ‘90s — but I held onto it for a few years. The thinking was this: that music was captured by a grand dialectical struggle. There were the “pure” artists on one side, and the corporate overlords on the other. These overlords were forever tempting True Artists into surrendering their integrity, while also milking their success by encouraging shallow counterfeits. In my review of Meet Me in the Bathroom last year, I wrote:

The internet has vastly diminished the influence of music tastemakers in print and radio and, relatedly, I think it’s also diminished the grip of the idea that “true” music is constantly besieged by corporatisation, creating an endless but fruitful struggle that obliges artists to reinvent and reassert themselves against the periodic triumphs of mediocre “sellouts”. In other words, “true artists” have to rescue themselves from their own success. Thus, the popularity of Nirvana birthed insipid wannabes like Bush, Creed and Nickelback, and now fresh saviours were needed to restore order.

The ’90s didn’t have a monopoly on this kind of thinking, but it does seem to me that the decade was obsessed with it. Last year, the cultural critic Chuck Klosterman, a Gen Xer ten years older than me, released The Nineties: A Book. He writes:

The nineties were not an age for the aspirant. The worst thing you could be was a sellout, and not because selling out involved money. Selling out meant you needed to be popular, and any explicit desire for approval was enough to prove you were terrible.

And:

The concept of ‘selling out’ — and the degree to which that notion altered the meaning and perception of almost everything — is the single most nineties aspect of the nineties.

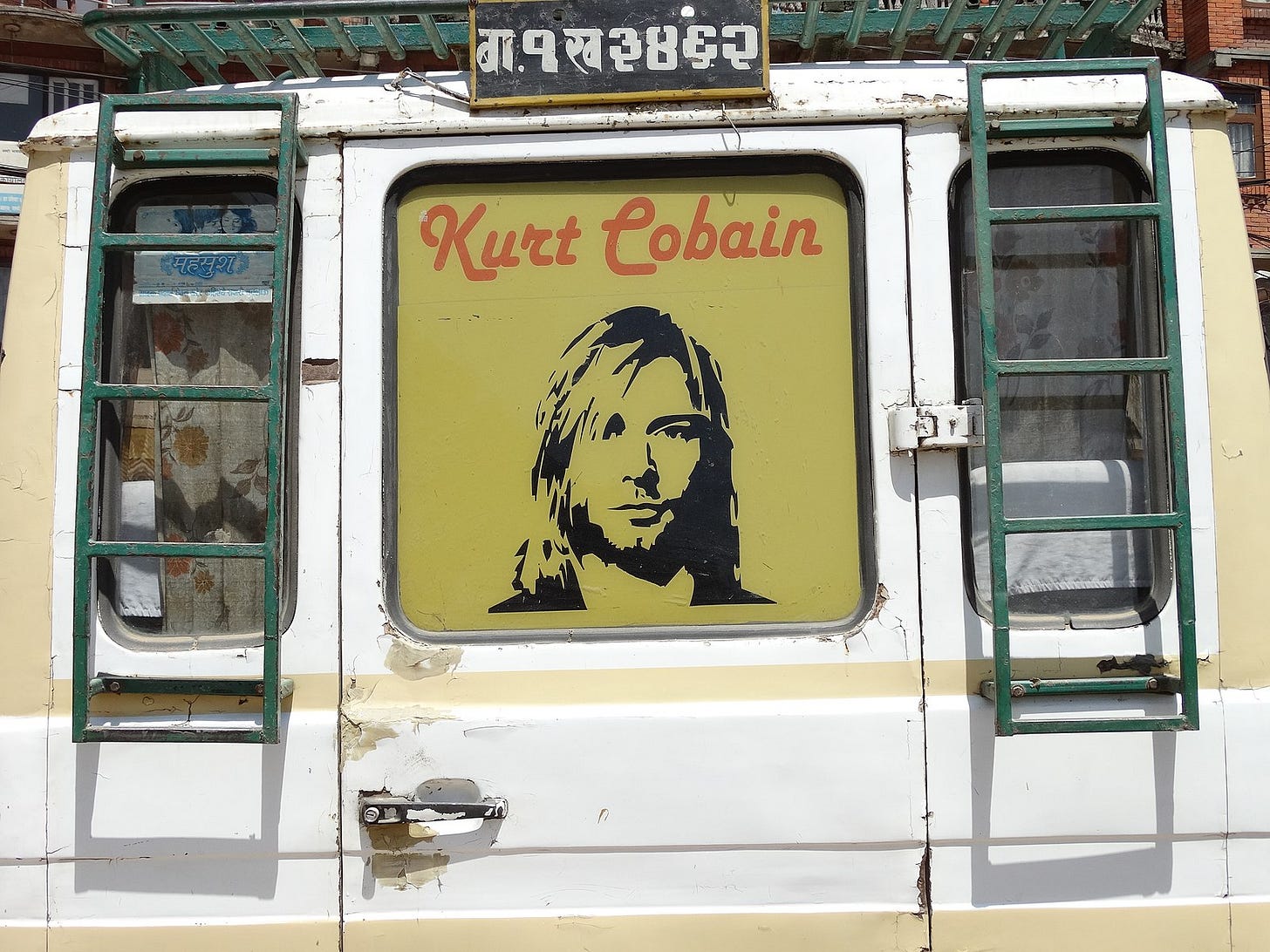

Klosterman muses on the paranoia and professional self-harm of this — of folks, even ones who thought the concept of selling out was naïve and violently inflexible, who still felt pressured to repress their desire for success. Kurt Cobain warned against this piety, telling Rolling Stone: “I don’t blame the average seventeen-year-old punk-rock kid for calling me a sellout. I understand that… And maybe when they grow up a little bit, they’ll realize there’s more things to life than living out your rock & roll identity so righteously.”

It seemed everyone was conscious of it, and that “sellout” was the worst thing you might say of someone — even if the word was often used simply to describe a band that you hated. Klosterman points out the various, absurd contradictions of “selling out”, and one seems very obvious to me now, even if it didn’t back then: If I was so concerned with the quality of mainstream culture and, by grand extension, the quality of our souls, why then would it have upset me to hear Sparklehorse on FM radio? (Sparklehorse albums were released by Capitol Records, by the way, a subsidiary of EMI — one of the “big four” global labels until its dissolution in 2012.) Why would I begrudge the success of a penniless artist?

The prosecution rests. But before I return to Lizzy Goodman, I might add a word in defence of my pretensions.

For many years in the 2000s, I lived in Northbridge, Perth’s nightclub district, which lies adjacent to its CBD on the other side of the (now tastefully submerged) train tracks. For a long, long time, Perth’s CBD was distinguished by becoming eerily vacant after close of business. There were a scattering of bars and clubs, sure, but the concentration of nightlife existed in Northbridge, which was notorious for its crime rates and gaudiness.

It was trash, I thought, and my opinion of the place during that time hasn’t changed much. On weekends, it transformed into a violent mecca, heavy with what we would call today “toxic masculinity”. Northbridge was the epicentre of giant “booze barns”, owned by just a handful of commercial barons, and which almost exclusively attracted the very young and organised crime gangs, some of which had commercial interests of one sort or the other in the district’s venues. Everybody else stayed away.

These giant barns and nightclubs were vulgar in design, intention and monopolistic weight — the difficulty of getting a bar license, and how jealously the major barons protected their own, transformed Northbridge into a violent pen, one which was both culturally and commercially hegemonic. Perversely, this status quo was maintained for a long time on the grounds that there was already sufficient booze in Northbridge, and thus other boutique licenses were redundant, or even unsafe. Whether through political inertia, a lack of imagination, or the rough influence of the hoteliers’ association, the sole answer to the district’s crime was always more cops.

But it was my neighbourhood nonetheless, and I was too proud to avoid it at night, even if my long hair, denim jacket and electric-blue flares were guaranteed to attract aggressive attention and screams of “faggot”. Walking home with dinner one evening, I had the shit kicked out me by four dudes. My housemate, a woman with a heart condition, was punched once, fell, and cracked her head on the pavement. But as she twitched on the ground, I was prevented from attending to her as I fended off the group. We returned home, blood-soaked. I was unrecognisable. If we defined ourselves in opposition to mainstream culture, well, there was fucking plenty to oppose in our neighbourhood.

*

When The Strokes’ debut went nuclear, they were celebrated as saviours of “authentic” rock — leaders of the latest whiplash against asinine corporate rock. As such, the boys had to be historicised: The Strokes were a revival of their city’s dirty/glamorous past, a reincarnation of The Ramones, Velvet Underground, Television, etc.

Now, being definitive about something as restless and recursive as culture is silly, but, well, you need starting places for conversations. And so I asked Lizzy Goodman if she agreed that The Strokes had been so framed and, if so, if they might have been one of the last bands to be defined in this way — as heroic participants in the Grand Struggle for Music’s Soul. “I think that’s unequivocally true,” Goodman says. “But with this caveat: the idea of saying somebody is the last of something is always dangerous, because there’s all kinds of stuff going on in the world that you don’t know anything about. And so there’s probably an example of some band and some scene experiencing, well, whatever. So, the ‘last of’ is too strong.

“But the broader theme that you’re getting at is true. There were these notions… I think it’s One Juan McLean, from the [dance-punk label] DFA world, who has this great quote from …In the Bathroom, where he’s talking about the notion of selling out as a kind of Boston kid. In his example, wearing Converse on the subway in Boston, in the late ‘80s, early 90s, could get you beat up. The semiotics of these things really meant something because there was this idea, loosely, of good and evil. There’s corporate overlords, and then there’s real stuff — you know, authentic art. And those two things can’t coexist. They’re at war with each other all the time.”

I might add that Goodman (like myself) isn’t suggesting here that she believed or believes in music’s cosmic battle of “good and evil” — or that it was ever so simple — only that the idea existed. But it was an idea that, coincident with the expansion of the internet, began to wane in the decade she documents. “I think what changed during this time is that those of us who were young, and maybe people who were weren’t that young too, had this expectation that an ‘Us versus Them’ mentality was in some ways going to always exist. And what happens in a post-internet world is that all of that gets sanded down, these ideas of corporate power being the gatekeepers — [and] Indie labels need to exist to make space for artists who can’t get attention on a big label like Capitol Records or something — all of that goes away, because the major labels are on their knees.”

Goodman’s book, if not the movie, tells the story of a music industry in historic flux. And so, too, are fans’ behaviour. Suddenly, artists were less concerned about selling out than they were about their fans’ piracy. In Goodman’s book, Tunde Adebimpe, lead singer for TV on the Radio, tells of fans bringing burnt CDs to concerts for him to sign — it hadn’t occurred to them that this might be insulting.

“There was a big difference between somebody who’s like my exact age, and somebody even five years older,” Goodman says. “Those five-years-older people would be so wary of any signs of selling out — someone licensing their song to a video game, or having it in the O.C. or something like that just seemed like ‘Ooh, is that gross? Like, we don’t do that.’ And for people my age, it was just like: What are you talking about? How else is anyone ever gonna make any money? Because honestly, the second Napster happens, the music industry, as we know it, is over — like, it is gone, you are not going to sell music anymore. And it’s taken a long time for that to fully land us where are we now, but it was true then. It was true that very day. And one thing my book covers is the process of the industry, and the individuals making art that need to engage with that industry, recognising that.”

Remember The O.C.? The once hyper-popular teen drama was produced by Fox, broadcast between 2003 and 2007, and had a taste for new American indie rock. Its theme song was provided by Phantom Planet, whose drums were played by Rushmore actor Jason Schwartzman, and it helped popularise (and possibly change the lives of) several bands.

One of those was Seattle’s Death Cab for Cutie. In 2003, I saw them in Perth’s modest Rosemount Hotel, in support of Melbourne’s Something For Kate. I had come only for the support act, and even though there was a long queue around the block for the headline act, almost no-one bothered to arrive early enough to see Death Cab. In fact, there were so few there that my shouted song request was not only heard, but played. Afterwards, we chatted to the band in the carpark as they loaded their gear into their cars. At that point, the band was six years old with four albums released. But they were still toiling.

By the time Death Cab returned to Perth just a few years later, they had featured on the O.C. soundtrack and were now playing in one of Northbridge’s giant venues to thousands. Was this selling out? (I don’t mean to solely attribute Death Cab’s commercial success to their featuring on the O.C. Ben Gibbard is a gifted songwriter, even if I have left them behind. But it didn’t hurt.)

“I do think, to answer your ultimate question, that The Strokes, as representative of this era, are the last band [to be celebrated in such a way],” Goodman says. “All these bands started in one world, and ended in another. And in some many cases, their first records were released in one world and their second record is released in a completely different universe.”

Today, that universe is vastly different again. The real money is made through touring and merchandise — and you need to be sufficiently large to sustain the overheads. We’re in the streaming age now, and we expect music on demand. “I love that people are looking for alternatives to Spotify and I don’t know how to explain to them that it has never been ethical or sustainable to expect to have unfettered access to the entire history of recorded music for $10/month,” Ross Grady tweeted last year.

But that universe, and the streaming economy, is another story. One I’ll write about soon.