There was a time, around 2010 and lasting for about as long as I lived in Canberra, that I wanted nothing more than to write like Sam Lipsyte. I’d read a couple of his short stories – and then his novel The Ask arrived like several cherry-bombs duct-taped together and mailed up my arse. It opened like this:

America, said Horace, the office temp, was a run-down and demented pimp. Our republic’s whoremaster days were through. Whither that frost-nerved, diamond-fanged hustler who’d stormed Normandy, dick-smacked the Soviets, turned out such firm emerging market flesh? Now our nation slumped in the corner of the pool hall, some gummy coot with a pint of Mad Dog and soggy yellow eyes, just another mark for the juvenile wolves.

I’d moved to our capital the year before, a pungent but not entirely charmless mix of naivety and idealistic ambition, to serve as a speechwriter – specifically and contractually for the minister of infrastructure, Anthony Albanese, though I preferred to believe that I was also a signatory to a grander, infinitely more romantic contract: that I, the undersigned, was also a lyrical organ of the Rudd Government, a balladeer for its transformative ambitions and benevolent wisdom, but also a diviner and amplifier of the People’s hopes, dreams and native egalitarianism.

My cloud of delusion was briefly soft and bright…

But after summarising countless “shovel-ready” projects, itemising infrastructure expenditure, and then dutifully lacing these shopping lists – they weren’t speeches – with dull, centrally-crafted talking points, I quickly woke from my feverish, self-important delusions. Though not before one of the minister’s advisors called to mock/harangue me for the inclusion of some reference to poets in a speech about building highways. And fair enough.

I was absurd, of course. Manifestly absurd. And years later, when I came to write my political satire, my own pretentiousness and naivety was the fattest target for my ridicule. But my anger and frustration, which quickly became thermonuclear, was not solely attributable to the sudden evaporation of my own ambition, and the sad, residual puddle of my self-conception.

No, there was also the shambolic and megalomaniacal Rudd, the accelerating politicisation of ministerial offices – which were now, like never before, staffed by lean, mean kids who’d replaced campus politics with federal government as the site of their hungry political apprenticeships. They had one eye on the mood of their boss; another on their future pre-selection.

There was also, relatedly, a largely confused and demoralised public service. The dreams of those in ministerial offices were not the same as those in their departments, and the animosity that spewed from incompatible motives were expressed in bitter caricatures: the public servants were politically naïve sloths; the political advisors were ruthless, short-sighted goons.

As it was, most people I knew in the department were sad, bored, and unconvincingly plotted their escapes. Unconvincingly because few had anywhere to go. They’d hit the ceiling, and they knew it. Their promises to leave were showy, had a real audience of one: they were convincing themselves of their own agency, the possible paths their theoretical rebellions could still take them. But they didn’t leave; could never leave.

And so the ambience of my department’s Communications Unit was sour torpor; the scent of well-paid soul-death. The place was smoky with unspoken eulogies for all of those possible life-paths that were once attractively bunched together twenty years ago but had now, irrevocably, converged here. At least the conniving, hyper-kinetic movements of the kids in the minister’s office suggested human vitality, possibility. It seemed sexy in comparison. But I wanted neither.

And so, Sam Lipsyte. There was music to his sentences, which were knowing, profane, hilarious. He was cynical, but sceptical of his cynicism, and he sang like a stoned wizard. His sentences – fuck, they spoke of a freedom and lyrical power that I desired, and while I drained serial pints of pale ale at the local, and riffed bitterly about the awfulness of the public service and the comic futility of my dreams, I wondered if there wasn’t a bong-wielding lyric-wizard inside of me – and, if so, how I might breathe the fucker into existence.

And so I tried.

*

Finally, Sam Lipsyte has written about music. The former “lead screamer” of Dungbeetle, an unsigned, righteously atonal NYC punk group that began and quickly dissolved in the first years of the ‘90s, has written a screwball noir set in New York City’s lower east side’s punk scene. Or post-punk scene. Or art-noise scene. Or “post-skronk propulsion” scene.

No One Left to Come Looking For You is a slim book, and unlike his previous, hems to a relatively coherent plot: Jonathan Liptak, aka Jack Shit, wakes to find his Fender Jazz Bass, which he wields for the unsigned, righteously atonal Shits, has been stolen by his housemate and lead singer, the unrepentant junkie who goes by the stage-name of the Banished Earl. Jack Shit must find the bass, and his lead singer, before their band’s final gig. A turnstile of dives, misfits, killers, bent cops and painfully bewildered parents are passed before he does.

While traipsing the streets of Alphabet City for clues, Jack understands that the Earl is more important to his band than his bass. The Banished Earl is the Shit’s earth-charge. “His brief includes but is not restricted to howls, whimpers, banshee shrieks, declamations, provocations, semi-ironic rooster struts, blind dives into the mosh pit, simulated or else revocable genital mutilation and, of course, spectacle. Spectacle above all else.”

Lipsyte was never, and I don’t think ever wanted to be, a great plotter. Martin Amis might have called him a “voice” writer. The pulpy, Scooby-Doo pursuit of the Earl and the missing bass skips along nicely, but is the skeleton upon which Lipsyte fits his nostalgia.

And it’s a charming nostalgia – vinegary, dark, honest. In the dim-lit dives, basements, and as-yet-ungentrified lofts of the lower east side, the chronically poor suburban refugees – the ones lit on dreams of replicating The Stooges, The Voidoids and Television – watch rival bands with envy or irritation. “He’s the drummer for Mongoose Civique, a band I officially despise for their polished songcraft and serious major-label interest, and possibly subconsciously admire for similar reasons. They are deft, quasi-heavy, hooky in that anti-hook manner, a sort of frat-house Nirvana… Ever since those Seattle boys broke the indie piggy bank open, all of the A&R douches from the big labels have been scouring the land for the next underground bonanza.”

Despite the centrality of music to Jack Shit, he finds little pleasure in the bands he actually sees, instead spying poseurs, frauds, and insulting triumphs of mediocrity. Everyone is a sellout, or a prospective sellout, and the Shits’ great virtue is that they aren’t good enough, or stable enough, to ever risk the corruption of signing with a major label. Or any label.

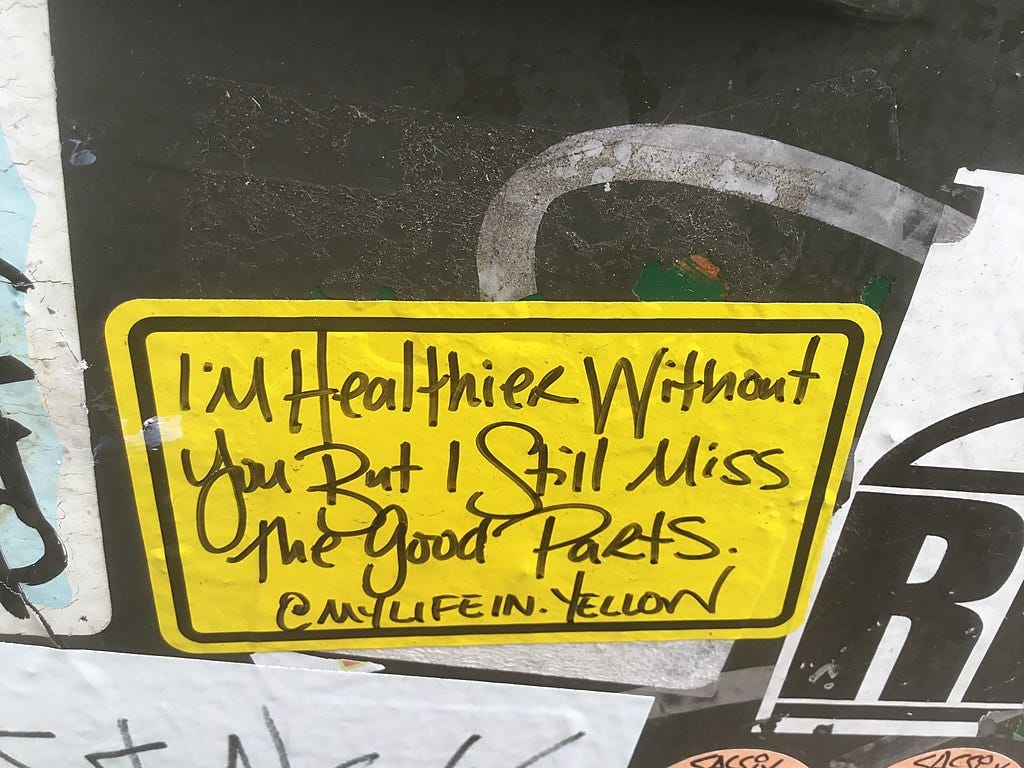

And yet, self-awareness occasionally penetrates Jack’s naivety: “I always find it amusing how we, the Shits, constantly complain about other bands being sellouts, but guys like Toad think the same about us. Somewhere, hunkered down near the god-head of bitterness, there’s a dude in the rattiest cutoffs ever who must think the same about Toad. It’s like Russian nesting dolls of impotent rage and insecurity.”

I love those lines. In Lipsyte’s remembrance, there isn’t an obscuring lens of sentimentality. There are drugs, plenty of drugs, and while Jack Shit searches for his Iggy Pop, he wonders if he wasn’t, perhaps sub-consciously, too weak in intervening in his friend’s smack enslavement because it helped provide the Earl with his glamour, his glow, his aura of unhinged, arch-angel danger. The Earl’s charisma held his band together.

Because the drugs aren’t pretty here: they scar, daze, trigger week-long spells of hysterical paranoia. There are illusory rats in the shower curtains; there are pus-bleak track marks.

Shit’s filthy, deranged. But passionate. Lipsyte’s early-90s lower east side is a glorious refuge, playground, and stage for misfits – as it was a site of crime, ideological confusion, impotent rage, drug abuse and self-destruction.

But the whole stage – the grand infrastructure for these misfits’ dreams – was threatened by more than bohemian excess. There’s money, developers. Goons and compliant cops. He’s only mentioned by name once, but the spectre of a younger Donald Trump floats sinisterly over Lipsyte’s caper – “He’s a symptom of the decay,” a character says of the future president. “The moral decay. The civic decay. The city’s been brought up by bastards like this. Someday there’ll be no ordinary neighborhoods. Just the ultrarich and their urban serfs. Meantime, we celebrate mobbed-up frauds like this guy.”

Trump is the great fraud that faked it until he made it, but as he’s buying up properties and employing muscle, the punks that occupy them are aggressively justifying their own authenticity to each other. Uptown, downtown: everyone’s obsessed with proving their own versions of legitimacy.

Meanwhile, Jack Shit occasionally wonders – between his sleuthing and fraught romances – when the fuel of his youthful ambition might ebb, when the “chronic penury” might get stale. It’s always cliff’s-edge, this negotiation of present and future. Aspiration vs delusion. Will vs exhaustion. And fucking all this up is the strange contradiction, virulent in the ‘90s, between desiring a “creative life” but resenting the commercial success that might sustain it.

The pulp plot of No One Left… is fun, but better is Lipsyte’s fictionalised reminiscence of New York City in the early ‘90s. The story’s antic, but his treatment of his past is enviably balanced: It was variously silly, filthy, dangerous. But there was also great freedom and glory in it.

Youth is a hot, expressive mess, and Lipsyte looks upon his with clear eyes. The naivety and loyalty. The indulgence and tenderness. He’s made a grimly amusing portrait of a time and place, which only masquerades as a crime caper, and it’s a rare current book in that its ambition is simply for you to look at it. He doesn’t say whether the time and place it describes was wholly good or bad. The past, for a writer at least, is not something to be disavowed, anymore than it is to be sanctified – it just was and it was and it was.