Craig Johnston was only a boy when he found himself very far from home. Actually, no, scrap that: “found” is the wrong word for such a wilful man – it makes him sound like driftwood – when in fact he’d engineered this trip and refused to accept that his initial failure and humiliation would be the end of his story.

It was 1975 when Johnston left Newcastle, NSW, for northern England to trial for Middlesborough Football Club. He was fifteen and had not previously travelled further than Sydney. To get him this far, his parents had sold their home and moved into a smaller one – an act of faith that Johnston was eager to repay.

Johnston arrived in December. It was snowing and the skies were grey. The local accent was heavy and often baffling to the teenager. In his first trial match for the club, a young Scotsman painfully took Johnston out at the knees. For the rest of the match, he struggled with his touch – he couldn’t control the ball, much less pass it well.

Unusually for a trial match, the club’s manager – the fearsome Jack Charlton, a former England international and World Cup winner – was watching. After the game, he strode into the change-rooms and excoriated the players. He reserved an especially brutal assessment for Johnston. “You’re the worst fucking player I’ve ever seen,” he told him. “Now fuck off back to Australia.”

In tears, Johnston returned to his hotel that was reserved for the club’s triallists. The hotel manager told him that she couldn’t retain his room – it was for club prospects only, and she’d be in trouble with Charlton if she kept him on. Sore, humiliated and now homeless, the hotel manager took some pity on the boy and told him he could stay in the coal shed out the back.

And so he did. That shed was Johnston’s home for the next few weeks, and in a nearby carpark he spent five or six hours every day practicing – or “trying to unravel the mysteries of the soccer ball,” as he tells me.

He used bins as obstacles, and chalk markings on the car park’s wall for targets. “There’s a simple science that says that a soccer ball is a round, perfect sphere,” Johnston says. “It doesn’t make mistakes. The person that uses it makes the mistakes, and the more you use it, the less mistakes you make.

“I was trying to understand what part of the foot and on what part of the ball produces what effect? Top spin, back spin, side spin. Pass, shoot, dribble, control. If you do anything for five or six hours a day over two years, you’ll get better at it. Malcolm Gladwell came on the scene years later and pronounced 10,000 hours [of practice for achieving excellence]. Well, I had my own saying 20 years earlier: 10,000 touches. And that’s how I got out of the carpark after two years and got into the Middlesborough first team.”

By 1977, Charlton had left the club. The new manager, John Neal, inquired about the strange Aussie in the carpark who cleaned the cars and boots of the players. The feeling around the club was that Johnston was “shit”, a failed triallist who hadn’t got the message. But faith was shown: Johnston debuted for the first team not long after his 17th birthday – within months, he was a fixture.

During his time in the carpark and coal shed, mates of his from back home – more talented players than he was, he thought – came to trial for the club too. They arrived, then soon left: they were too overwhelmed by homesickness. “I wasn’t homesick because I blocked it all out of my mind,” he says. “What I did, mentally, was to tell myself that one day I would get to do what they do – all those rites of passage of a young Australian on the coast – so just keep doing what you’re doing now. And I owed Mum and Dad. I owed them.”

In 1981, after 64 appearances for Middlesborough, the country’s largest and most successful club, Liverpool, paid a then club-record transfer fee for Johnston. They weren’t alone in wanting him: Nottingham Forest’s famous manager Brian Clough tried to charm and cajole the Australian into signing for him. But Johnston’s father had advised him to choose Liverpool. Craig Johnston was going to Anfield.

*

Johnston was born in South Africa in 1960 to Australian parents, before the family returned to NSW when Johnston was just a few years old. His mother was a school teacher and, he says, “elegant, articulate, sophisticated, cultured, well-travelled”. His father was very different, Johnston says, but “very loveable”. A mechanic who loved a beer and a yarn, he was also an athlete and once had his own trials for several British clubs when he was a teenager. It was his father who wrote to several clubs on behalf of his son, in an attempt to secure their interest in trialling him. “You’re the product of your parents,” Johnston says, “And thank goodness I got my mother’s brains and my father’s legs, and not the other way around”.

*

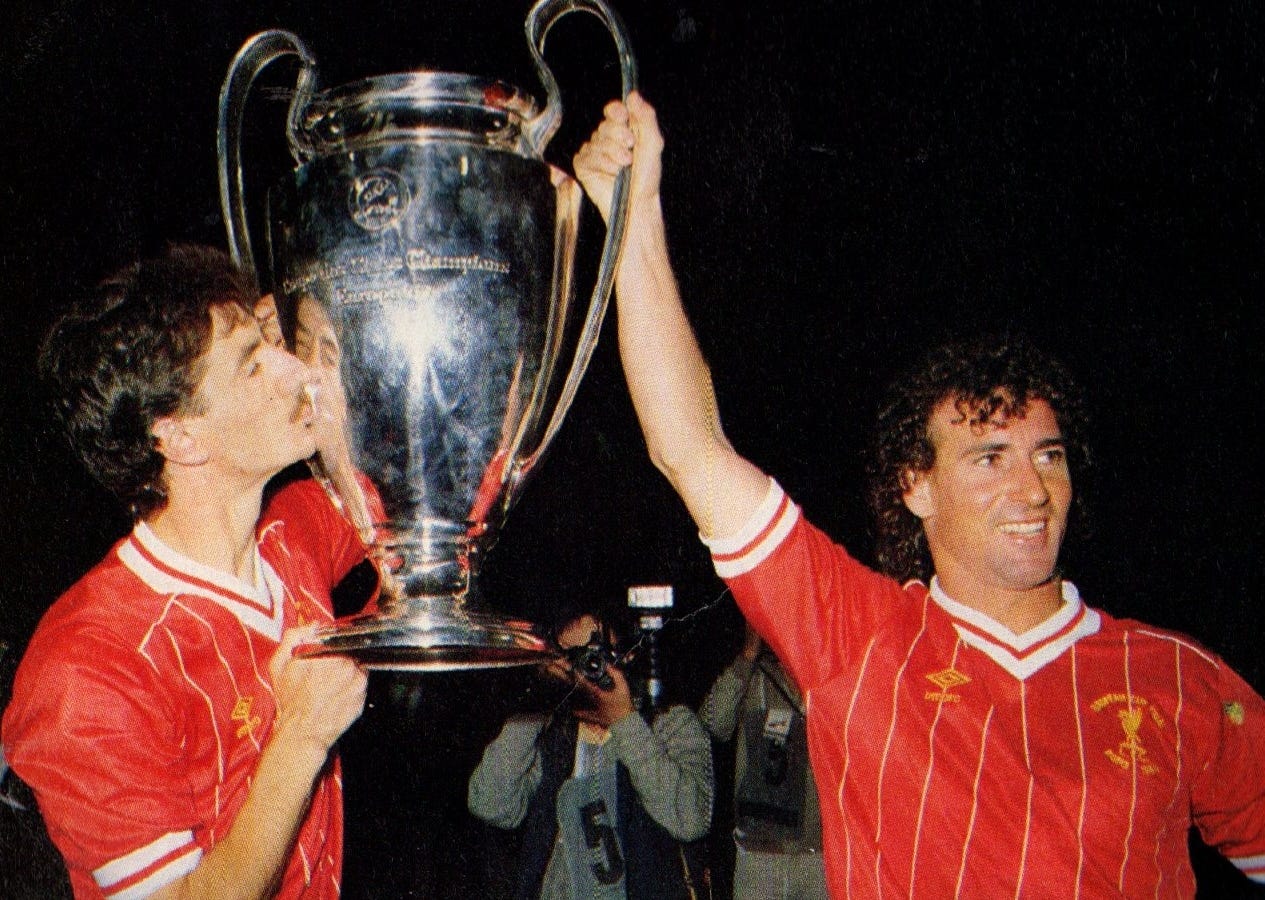

Johnston played for Liverpool when they were the best team in the world and no other Australian player has enjoyed more European club success. Between 1981 and 1988, Johnston played 271 times for Liverpool and helped the club to an astonishment of trophies: five league titles, a European Cup and an FA Cup. The latter came in 1986, when Liverpool beat their great rivals Everton 3-1, and Johnston became the only Australian to score in an FA Cup final.

There were more skilful players in the squad, but few ran as hard or as enthusiastically as the man they called “Skippy”. From a young age, Johnston had also been learning – and acquiring – the same flintiness and dedication he saw in the older generations of footballers who now worked as managers, men who were often raised poor in working-class families and coal mining towns. “For a time there was no such thing as a professional soccer manager,” Johnston says. “What there were was, was a coal pit manager, and the local pit manager who liked his sport became a soccer coach. There weren’t any coaching badges as you have now. These were just working-class blokes who came out of the mines. There’s a famous backdrop to this, what’s called the Ayrshire Triangle – the pit mines up in Scotland in the triangle made between Ayre and Glasgow and Edinburgh, and the likes of Bill Shankly and Jock Steen and Alex Ferguson, to name just three, came from there. They were strict disciplinarians, and their managing was based on tough, hard men saying tough, hard things to other tough, hard men. And you had to deliver or die. I learnt a lot from listening to those blokes. Bill Shankly used to invite me over to his house to have a cup of tea with him and his wife Nessie, and I ended buying a house just behind his. They more than anybody influenced the way I thought about football: about steely nerve and dedication. No excuses, just delivery.”

*

Johnston’s athletic retirement came suddenly, prematurely and was compelled by personal tragedy. In late 1987, as Johnston was preparing to go to his club’s Christmas party, he received a phone call from his mother: Johnston’s younger sister Faye had suffered a terrible accident. While on holiday in Tangier, she experienced severe butane poisoning from a faulty heater in her hotel room. She would remain in a coma for three weeks, and suffered a profound and irreversible brain injury.

Johnston told very few people at Liverpool FC at the time. There was the fear that the news might leak, and distract the lads. So Johnston largely kept it to himself, as he wrestled with his pain and sense of guilt – there was now an awful discrepancy between his glories and his sister’s condition. Football hardly seemed important.

“I just felt so bad when it happened,” Johnston says. “I was running around football fields and Wembley Stadium and had the world at my feet, and it was time to stop thinking about myself and being selfish and go back home to help Mum and Dad with Faye, because we all thought that she would get better and she would come out of the coma and the vegetative state that she was in because of the accident. But the problem is… because I’d walked away not only from Liverpool at 27, but the game, I had no income coming in and Faye’s hospital bills were getting higher and higher and that was taking all the money that I’d ever earned. We were all in a pickle, but we all had to be together. And Mum and Dad, again, copped the brunt of sacrifice for their children. Mum had to retire from school teaching, and Dad fundamentally had to work harder as a mechanic at the council. I made that decision wholly based on what my parents had done for me, and it was my turn for payback.

“We don’t like to talk about it because it’s so sad. Faye’s still with us, but in a non-conversive state and is still in a nursing home. The unfortunate thing is, Faye never got better. The good news now is she’s got two or three or four carers that she’s had over the years and they are the most beautiful people I’ve ever met in my life.”

*

You might think of Craig Johnston as a Renaissance man. Footballer, photographer, surfer and inventor. In the early 1990s, he designed one of history’s most famous and highest-selling boots – the Adidas Predator. I thought of the years he spent on several prototypes, and the years he spent fruitlessly trying to attract the faith of manufacturers, and in my head this chimes with those years in the carpark – not only the dedication, but his application of scientific inquiry and experimentation.

Sometime in the late 1990s, while enjoying a drink in a Dublin pub, a journalist recognised him and bought him a pint of Guinness. The reporter wanted to know something: How does a footballer become an inventor? Johnston told him he had it arse-backwards: “Mate,” he said, “I was an inventor who became a footballer”.