Probably my favourite Aussie band of all time, The Go-Betweens were formed in Brisbane in 1977 by Robert Forster and Grant McLennan – teenagers then bonding over Byron’s poetry, The Velvet Underground and countless sticks of weed.

They released their first album in 1981. Send Me a Lullaby wasn’t great, and its recording bitterly fraught, but their second, Before Hollywood, is a classic. They would make several more classics after that.

In the band’s first period, between 1977 and 1989, Forster and McLennan remained the only stable members – the group’s composition otherwise fluctuating, as per the storms of drugs, duelling temperaments and soured romance. Members of the band would become lovers, then split.

And so did the band in ’89, having recorded six albums. When they did, they’d found international acclaim but sold very few records. “The break-up of the band in 1989 was savage and abrupt,” Forster wrote in 2006. “Grant and I had had enough. We’d written six lauded albums and the band was broke. In the end, we were doing Sydney pub gigs to pay ourselves wages. It was a nasty treadmill.”

In 2000, having recorded their own solo work in the intervening decade, Robert and Grant got the band back together. In this second period, they released another three albums – the best of which equalled their work in the ‘80s.

Then, in 2006, Grant McLennan died at home of a heart attack. He was only 48, but his death was preceded by years of hard drinking and heroin use. When he died, McLennan was preparing for a grand house party. Forster arrived for it and saw an ambulance in his old friend’s driveway. “My baby’s gone,” McLennan’s girlfriend Emma told Forster, and so he was.

That year, Forster wrote a remembrance of his friend in The Monthly where he had just begun as its first rock critic:

“[Grant’s] refuge was art and a romantic nature that made him very lovable, even if he did take it to ridiculous degrees. Here was a man who, in 2006, didn’t drive; who owned no wallet or watch, no credit card, no computer. He would only have to hand in his mobile phone and bankcard to be able to step back into the gas-lit Paris of 1875, his natural home. I admired this side of him a great deal, and it came to be part of the dynamic of our pairing. He called me ‘the strategist’. He was the dreamer.”

Together, they’d written some of this country’s best songs.

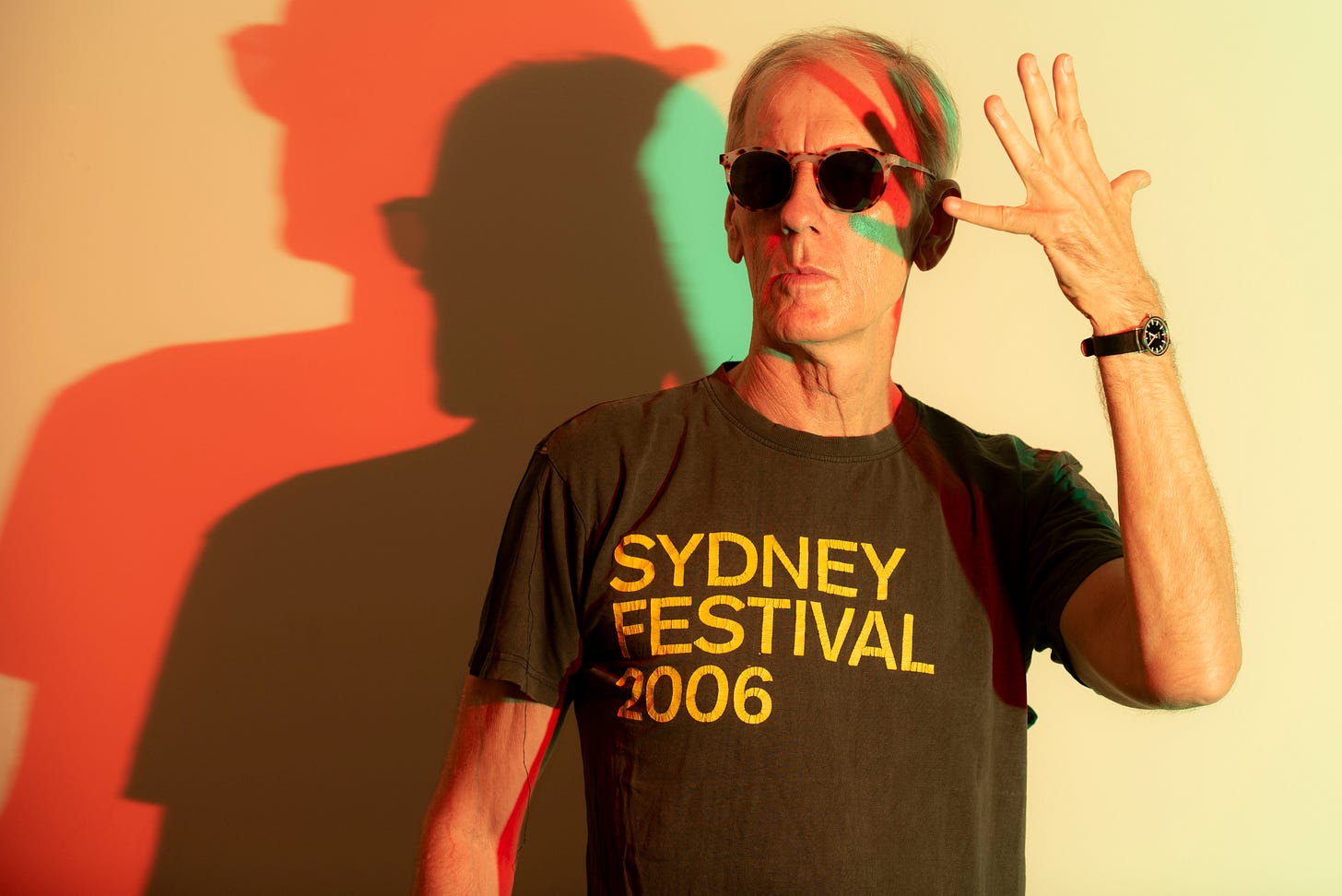

Robert Forster has released eight solo albums — in May, he’ll release his ninth. It’s called Strawberries, and was produced by Peter Morén, of the Swedish group Peter, Bjorn & John, and recorded in Stockholm. He’d long wanted to record there.

In the album’s liner notes, Forster writes: “Recording for me has always been about location. I’m not someone who has ever owned recording equipment; assembling an album slowly at home is not my thing. Recording gets me out of the house. I’m like a filmmaker, I want a new town and a strange landscape. This allows me to imagine albums I could make. The Rome album for instance. Or recording in a bare hotel room… And there was always Stockholm.”

Why were you dreaming of Stockholm, Robert?

There just seemed something exotic about it. And it’s very distant, obviously, from Brisbane. A very different climate, and different mentalities of the people. I've been going there since the ‘80s. And so I’d see Stockholm every five or 10 years. And there was just something about it: there’s a lot of water, it’s a beautiful city, it’s quite remote for Europe. It’s always drawn me.

On your next album, there’s a song called “Breakfast on the Train”. It imagines fictional people, but was inspired by your own adventures touring Europe with your son. It must be a joy to have an adult child with whom you share passions and talents? It seems like a beautiful thing to me.

It is a beautiful thing. And it started very young with Louis. It started when he was five or six – it was just a passion of his so early. If it had started when he was 12 or 14, then I might have thought “oh, one of my children is aligning themselves with what I'm doing”. But the fact is that he wanted this nylon string guitar at six or seven – and then it just got more intense.

It’s wonderful because it’s always something that you can go to in a conversation. It’s an ongoing dialogue about music, about songwriting. And that's really beautiful. I'm not saying that makes it better if the child has fewer of your interests, but it's just this ongoing, bubbling thing. And then we were on the road together. I just never thought that that we’d be on stage together, really, because he was cutting his own way. So that was a beautiful tour to do.

Did you ever bite your tongue about your own reservations or experiences when he was younger and wanting a career in music? With The Go-Betweens, you made extraordinary records and had great success but, by the end of the first period of the band, you were still poor and exhausted and it had badly taxed you, psychically—

—Yes.

—So how, as a father, did you encourage your son’s passion while being honest about your own experiences – did you ever bite your tongue?

That’s a very good question … My conversations with Louis, and they’re ongoing, tend to be a lot more about music and songwriting and things we like and enthusiasms and him showing me stuff, and me showing him stuff, and us talking about artists. It’s a lot more on the craft side of it.

The business side? He wanted to do that by himself. And the last thing I wanted to be was the overbearing show business father. We both formed naturally into this conversation about music and the art of it, and we’d play together. And he was in a band. So I didn’t want to be not only the overbearing parent of my child, but the overbearing parent in a group of musicians.

You’ve spoken before about the influence of AM radio on you as a child — how the radio switched you on to music…

I was basically raised on ‘60s and early ‘70s AM radio, because I was in a family where there was no record player and none of my family were musical. So, it was just what was coming through a transistor radio. It just caught my ear and I stayed with it, having no idea that I was going to write songs myself. A real favourite band of mine in the late ‘60s, when I was 10 or 11 years old, was Creedence Clearwater Revival which I now see was about the rootsiest, roughest music that I could get my hands on, you know. I was drawn to the raw, but that was the width of what I could hear.

In those young years, you were admiring the kind of Baroque compositions of Brian Wilson or Paul McCartney or David Bowie, but then you come across Jonathan Richman and the Ramones. The Ramones release “Judy is a Punk” and “Blitzkrieg Bop”, and Richman’s Modern Lovers release “Road Runner” and they’re powerful and soulful tunes, but super simple. And I think you’ve said that you heard them and thought: “Oh, this is encouraging”. That making music didn’t need to be intimidating, and that you could make a virtue from your limitations.

Oh, yeah. When I started playing the guitar, when I was around 15, I was listening to Bowie and I was listening to Roxy Music, around ’73 or ’74. I wasn’t into prog rock, but Bowie sounded very complicated. Bowie is very sophisticated. I was listening to Hunky Dory, and I thought: there’s no way I can do this. I cannot write “Life on Mars”. I’m 15, and just learning basic chords. And so I didn’t really see a door to songwriting, even though I was starting to feel that I wanted to do it.

Then hearing the first Ramones album – that was the first time I just went, “Oh my God”. I got the record on import when it first came out, in April 1976. Johnny Ramone is just playing bar chords, and there’s no solos, right? I didn't have to worry about being Eric Clapton, or Jeff Beck or Jimmy Page. That was a burden off my back – gone. And it was very lyric-based, which appealed to me. I thought I had something to say at 18, as muddled and weird as it was. The door opened.

And your singing?

My voice wasn’t strong. I couldn’t sound like John Fogerty or Neil Diamond. I couldn’t sound like Bowie. They’re all singing out – their voices were big and glorious. But then I heard Lou Reed, and I thought “Oh, right”. You could have a tone of voice that’s not classically rock or classically pop, and if you’ve got something to say, it can work.

And Jonathan Richman was an even more extreme and weirder version of that, but it was totally convincing to me, and I felt that he was totally convincing to other people. And it was almost as if the voice went with the words, and the words went with the band. And so that was just the start of my thinking of what I could do.

Richman fascinates me. I’ve long been charmed by his music, but I assumed for a long time – I think because I’d become accustomed to a lot of ‘90s rock, where the posture was often grounded in cynicism or irony – that his childish sound was an ironic, faux-naivety. But I later realised that he was 100% sincere. And it’s delightful.

He’s a central figure in what I did. I could hear when the Talking Heads started that David Byrne had listened to that first Modern Lovers album, and Byrne took it in a different direction. And then, of course, Jerry Harrison from the Modern Lovers joins the Talking Heads, and that’s no coincidence.

I particularly liked the second album that he made when he had the new band, and that was an influence on The Go-Betweens as well. It was with a band, like a drummer and another guitar player, but it [sounded] very sort of early ‘60s, before The Beatles, almost. It just had this sort of late ‘50s Buddy Holly feel, which I really adored.

Can I come now to The Go-Betweens and your meeting Grant. He wasn’t a musician when you first met: he wanted to be a film director. But you introduced him to the bass guitar, and you’ve said before that his starting on the bass influenced how he wrote melodies. Can you tell me about that – how starting with bass might have influenced him as a melodist?

I think it was crucial. I’d written a couple of songs like “Lee Remick” and “Karen”, a few of those really early songs in late ’77, and I knew that I could teach him to play bass to these songs because the songs are quite simple. So, I expected him to just go from note to note to note, very basic bass playing, which he would have completely got by with. But Grant was just a fluid, melodic player. It was quite obvious early on that he was a more melodic player than I was, and more of a natural musician than I was. And so he played bass in The Go-Betweens for the first four years.

And when he went to the guitar, about six months after the bass, he was already a lot more… I was more blocky chords, and he was more note-y. That was the big difference. I just assumed it came from his bass playing. It’s like McCartney. Like McCartney, Grant had that ability to have riffs and notes and his bass playing was very note-y, as opposed to being a chunky rhythm machine. He could write chord songs, but they often started as riffs or note clusters – and much more so than me.

So as teenagers, Grant’s introducing you to French New Wave cinema, and then you introduce him to the bass guitar. Did it surprise you how quickly he became good? Was he surprised at his own latent ability?

I think he would have surprised himself. The first inkling I had was not about his songwriting, but just how beautifully he played bass to my songs. And he started singing as well. So, he had a singing voice, which, of course, for a songwriter, that’s perfect. And in a way, he had more of a classic voice than I did right from the start.

But weighed against all this was that he was the most creative person that I’d met. That’s why I wanted to be in a band with him, because he was on fire… We were listening to the same records, and I just thought we were sympathetic as people. I didn't want to stomp on him. I just thought— it was like a Lennon/McCartney dynamic, or Keith Richards and Jagger. We’re 200 percent, where other bands are 100 percent. There was some arrogance.

And your sum was greater than your parts – is that what you mean by that?

Yes, definitely. You know, starting a band in Brisbane in the late ‘70s is hard enough as it is – you’re up against the wall. How are we going to get to London? How are we going to get to New York? How are we even going to play in Sydney? Are we ever going to make an album? We're living in Brisbane in a share house in the late ‘70s, so the attitude was always: We’ve got to throw everything at this. We've got to use every strength we have and we've got to make an impression. We were willing to put it all in one pot.

How did your temperaments work together? Were they usefully different? There’s a new book out now by Ian Leslie about the creative partnership of Lennon and McCartney, and he says – and it’s been said before – that it was defined by intense feeling. Platonic, but intense. That there was enormous fondness there, and a magically useful competitiveness, but that the intensity of feeling was also volatile. How did your creative partnership with Grant work?

I think a major difference with Lennon/McCartney – just to take that example you brought up – and why our relationship lasted, was because there wasn't a Lennon between us. You know, there wasn’t the Alpha, brooding bigness. There wasn’t the domineering Lennon to the more acquiescent, more sensitive McCartney. That was never the dynamic between Grant and I. I think that’s why we lasted. There wasn’t an Alpha dog. Both of us were quite passive in a way.

And that happened naturally?

Yeah. And also, remembering from the mid ‘70s, we'd seen – and this was unspoken – but we both knew it: we'd seen Lou Reed and John Cale. They’re great on the first album, and then John Cale goes and the Velvets are still good, but, you know…

Grant and I worked magically from the get go. We didn’t have to try… But Grant was different. He was more social and had a wider group of friends than I did. People saw things in him early on, which they didn’t see in me. When we first met [as teenagers], he's getting all these great jobs and I’m working in a brush factory to get money. He just walks into a cinema, and then he’s working in the cinema. He walks into a record shop, and then he’s working in the record shop. People are seeing things in him, you know, at 17 or 18, that they weren’t seeing in me.

And I saw something in him as well. I wanted to work with him. It was his great knowledge, he was very personable, tinged with a bit of arrogance. He could talk about poetry, cinema, music, literature fluently and at a deep level at 17 or 18.

[Before you read on, I encourage you to watch this clip of Robert and Grant talking about the origins of “Cattle and Cane” in a lounge room before playing the track together. I’ve always found it magical.]

Can I skip to a later part of your career that I’m curious about, and it’s when you become The Monthly’s first music critic – you recently performed at the magazine’s 20th anniversary party. When you were asked, you had almost no writing credits at the time, and so I know that you felt flattered because the invitation spoke about what you might do rather than what you had done. Were you anxious about beginning a career as a music critic?

It came completely out of the blue. And a really pertinent point was that the magazine didn't yet exist. I couldn’t see it. I didn’t know the world of publishing, and I had barely written anything at all. But one day Christian [Ryan, The Monthly’s first editor] told me that Helen Garner would be the film critic. And that was a real moment.

And then the only other thing was something I had to work through in my head, and this is why I was worried about it: that if I was going to go from being a musician and a working music critic, well I couldn’t see an example anywhere in the world. But I sort of thought, well, my whole career has been about doing the unexpected at times. And writing and that whole world of music journalism has always fascinated me.

I never saw the divide between [musicians and their writers]. Most music journalists that I met from the late ‘70s onwards, they’re interested in film, they’re interested in books. Very rarely did I meet one who was just interested in music. I didn’t see music critics as folks who didn’t understand music because they didn’t play an instrument. That never had any credence for me.

So, I said “yes”. And thank God I did. Suddenly I was off on a new adventure. I was 47 at the time, and I realised that this could be something new.

Robert, can I finish by going through your 10 Rules of Rock and Roll which you listed at the beginning of your compilation of music writing 15 years ago. I’m curious to know if you still agree with these, or if you’ve disavowed any – or perhaps you might just like to qualify some.

Sure.

Number 1. “Never follow an artist who describes his or her work as ‘dark’.”

I agree with that even more now than I did then.

I’m pleased. Okay, Number 2. “The second-last song on every album is the weakest.”

Yes.

I don’t need to debate that with you. Number 3. “[Members of] Great bands tend to look alike.”

Yes. Because they’re always hanging out together, especially while young. The Beatles, after 10 minutes in Hamburg, they’re all in leather. They’re in practice rooms and they’re on stage and they’re being photographed. They morph together.

Number 4. “Being a rock star is a 24-hour job.”

Still totally believe that. Bowie woke up as Bowie. And if you ever forget that, you walk out of your hotel and get a coffee and people start screaming: even if you forget, the world will remind you.

Number 5. And there seems to be an implication of affectation here, Robert. “The band with the most tattoos has the worst songs.”

I still agree. I see people in bands head-to-toe in tattoos and I think: “When is the songwriting being done? When’s band rehearsal being done?” That’s what I wonder.

Fair enough. Number 6: “No band does anything new on stage after the first 20 minutes.”

Definitely. It’s sheer exuberance, mainly. You go on and you show all your tricks early because you want to get the audience, and you know that if you’ve got them, you can keep doing the same tricks, and an hour and a half later people are still enthralled. I think it's very hard if you're a performer to save something, and reveal something new in your stage presence or your show, in the 71st minute of the show.

Number 7: This is the one I think I take most umbrage with Robert, and I present Jeff Tweedy of Wilco as the contrarian example. But your seventh rule is: “The guitarist who changes guitars on stage after every third number is showing you his guitar collection.” Do you still agree with that?

Totally. I see it all the time. I stand in the audience and I see the singer songwriter change their guitar. I'm listening to the concert and I hear no sonic change.

I guess there’s a problem if you’re not hearing any change in sound.

There’s none, and if you see any footage of like The Stones or The Doors or Creedence in the ‘60s, there's no guitar changes. Keith's playing the same guitar all the way through. It makes no difference. And it's because in the ‘70s and beyond, if you’re a successful band, you've got roadies. And so what do roadies need to be doing? They need to be bringing your guitar collection out that you bought off the royalties of the people that are watching you. And you show them. And people respond. “Ohhhh, that’s the 1961 Les Paul!” People respond. But there’s no sonic change.

Number 8: “Every great artist hides behind their manager”.

Yes. That’s eternal.

True. Number 9: “Great bands don’t have members making solo albums.” That seems fair enough.

As a general rule, I think that still works.

I think if The Beatles stayed together in some part-time fashion, say coming back together a few times in the 1970s to record something, then you’d have conflicted loyalties. Are you bringing your best work back to The Beatles studio? Or are you keeping it for your solo album?

Yes. I think, you know, as a band the wall’s up. It’s like: this is the only thing we’re doing. And every bit of energy, every bit of juice, is going into this.

Finally, your tenth rule of rock and roll is: “The three-piece band is the purest form of rock and roll expression.”

Yes, especially on stage. As soon as you bring in a rhythm guitar or a piano player, there’s someone else providing padding, or knitting it together. When it’s a three-piece, there’s nowhere to hide. I’d count a three-piece band with a lead singer as a three-piece as well. A great example to me – one of the most amazing bands of all time – is The Doors. And the big distraction with The Doors is Jim Morrison, he’s probably the least talented person in the band.

Robert Forster’s Strawberries will be released May 23.

He owned a wallet and a watch.