I made the mistake once of buying Nick Kent’s memoir, Apathy For the Devil. It was released in 2010, an age after the 1970s that it takes as its subject, when Kent was a strange, notorious and semi-gifted writer for London’s New Musical Express. This was the decade when he dated Chrissie Hynde, was whipped with a bike chain by Sid Vicious, and had the honour of Keith Richards puking on his leather jacket. You know, the good years. The years when he was called the “world’s greatest music writer”.

But Kent’s book was such that after only a few pages, it compelled me to literally throw it across the room. I wanted to damage it. And now, years later, I’m searching my shelves fruitlessly for it, in the hope that I can directly cite its awfulness – but I think I must have pawned it to a second-hand bookstore. I regret this now. Because here’s what I’d like to prove with his own words: that this allegedly electric wordsmith was a fucking hack, and his book, at least the few pages I read, were slabs of cliches joylessly cemented together.

On publication, Kent gave an interview to his publisher for publicity. In it, he is both pompous and painfully inarticulate, a combination to which I have an acutely adverse reaction. It’s like watching a junkie Baron exhale from a hookah pipe, and mistake the smoke for speech. He’s vague, platitudinous and lazy, and yet his chin-scratching self-regard somehow survives the dull wreckage of his tongue. He can’t remember the ‘70s anymore than he can see how boring he is, and truly – watching this, I want to set fire to his goatee.

If Kent was ever an artist, the artistry didn’t survive the junk and louche posturing of the ‘70s. Writing can possibly be improved by certain substances, or at least the mood in which to write can be productively altered, but it’s a craft in the end, and if your only discipline is scrounging money for the next hit, then it’s long odds that, if you survive, that your writing will too.

So predictably, Kent flamed out and left London for Paris in the ‘80s. A clichéd casualty of the filthy/glamorous, Lord Byron-with-a-leather-jacket role he enjoyed. His legacy is meagre: perhaps half a dozen decent essays or profiles. If you think I’ve been harsh, here’s his old colleague, Julie Burchill, reviewing his memoir for The Guardian:

As I said, given the state of the storyteller, I expected this book to be lies, but I hoped it might be fun, too. Sadly, laughs are in short supply despite the risibility of the central character – though one would surely have to have a heart of stone not to laugh at the religious conversion near the end – and I say that as a religious convert myself.

That this is the stuff of Toytown legend masquerading as some sort of epic adventure is given the final embarrassing twist by the depiction of Kent on the cover sporting drawn-on Satan horns and goatee beard. To paraphrase Python, he wasn't the devil – he was just a very naughty boy. That he has grown into a silly and grumpy old man will come as no surprise whatsoever to those of us who were unfortunate to have to share space with the stinker way back in the day.

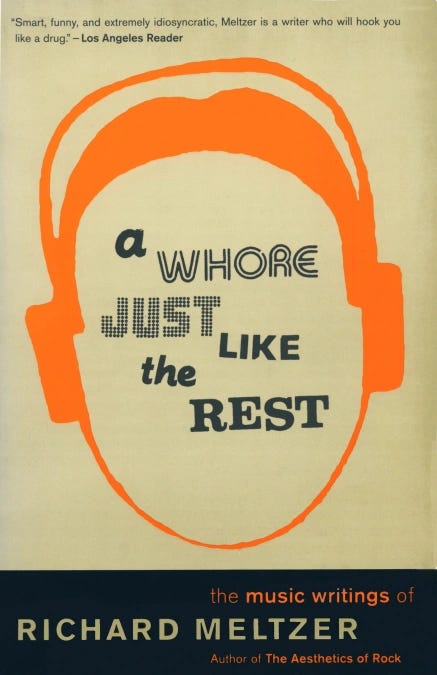

Then there’s Richard Meltzer. “One of the inventors of rock criticism,” reads the blurb of my fat anthology of his, A Whore Just Like the Rest, released in 2000. An American, Meltzer wrote for underground ‘zine Crawdaddy in the ‘60s, and published his first book The Aesthetics of Rock in 1970. It opens with this line: “This is a sequel, not a formulation of prolegomena”.

In his twenties, Meltzer had swallowed a little Continental philosophy alongside the barbiturates – he was fond of Kant – but like Kent, he worshipped at the altar of his own passions, and his writing was like a jukebox stuffed with deranged tics and suffering a faulty wire. Reviewing Cream’s second album, Meltzer opens:

“Mere uniqueness. Cute little vocals on one end, and top-flight instrumental extravaganzas on the other, slammed together through some sort of DONO-ZAPPA AVOIDANCE PRINCIPLE too, just a little too elusive to put the finger on. Not an ounce of eschatological viscera. With Cream, got to start with the NON-BUMMER GRID OF ANALYSIS: there are no true primary bummers, just non-bummers and non-non-bummers.”

Reading Meltzer was like being button-holed at a club by the resident gadfly, who’s massively coked and imposing some spit-flecked rant which to you is gibberish but feels to him like revelation. Perhaps at some point he really did understand Kant, but you wouldn’t know it – he tosses off words like “prolegomena” amongst the CAPITALISATIONS and the “fucks” and the “pus” and I think we’re meant to be impressed by the hot mix of philosophy, passion and junkie street bravado – and perhaps we would, if most of it made sense. (Richard Hell, a better writer and punk musician, described Meltzer as “execrable”.)

Here, even more than Kent, was a man who believed that the Spirit of Music might be expressed by the hack through emulating his subjects’ drug-buzz and then vomiting… well, anything that comes to mind. Here was hedonism masquerading as serious experimentalism; drug-fucked solipsism as the alleged key to a brave new lyricism.

It requires enormous patience to read. Such an approach was, by definition, indulgent – the writers’ reaction to the music is sacred, it’s everything. As the band was plugging in, so too was the writer jamming their antennae into loose, high-voltage sockets. They channelled their adrenaline, their thesaurus, and their dreams of being the next Kerouac — the ultimate ecstatic riff-lord.

As embarrassing as much of their writing was, I don’t think they were entirely wrong. There is something a little perverse and futile, I think, in writing about music in the first place. Unless one is writing some straight history, there’s an unbridgeable gap between the two forms. And merely reciting album sales and a song’s chart peak can’t capture a song’s importance, can it? It’s dry data, and that’s not what Kent and the other filthy boys were about. Fair enough. Music’s importance existed elsewhere, in feeling, in vibes, in danger, and they felt duty-bound to court their own danger to be properly receptive to it.

And there was something else – an idea of experimentally melting writing down to a state comparable to music. In his first book, Meltzer wrote:

I have thus deemed it a necessity to describe rock ’n’ roll by allowing my description to be itself a parallel artistic effort. In choosing rock ’n’ roll as my original totality I have selected something just as eligible for decay as my work, and I will probably embody this work with as much incoherency, incongruity, and downright self-contradiction as rock ’n’ roll itself, and this is good.

I have great sympathy for this – but only until I actually read what Meltzer wrote. Then it seems not so much the declaration of a bold artistic vision, but an alibi for the ensuing incoherence.

But perhaps the godfather of these early rock critics is Lester Bangs, who was played by another doomed figure – the late Philip Seymour Hoffman – in Cameron Crowe’s semi-autobiographical movie Almost Famous.

Before cinema, Crowe was a very young critic himself, for Rolling Stone, and he sought Bangs out for advice when he was a teenager. It was the 1970s when he did, and as a critic for Creem, Bangs had become an underground legend for his wild, obsessive, contrarian and sometimes beautiful riffs on pop music. Bangs died of an accidental overdose of several prescription drugs in 1982, at the age of 33, and in a posthumous collection of his writing, Greil Marcus wrote that “perhaps what this book demands from a reader is a willingness to accept that the best writer in America could write almost nothing but record reviews”.

Bangs was good, sometimes very good, but this still strikes me as absurd if we consider the other writers/essayists then working in the ‘70s (Sontag, Baldwin, Mailer, Didion, etc). But if there’s one man of this clan – and they’re all men – whose work has survived today, it’s Bangs. And I’m glad for it.

There are a few essays that I read at least every two years, and have done for nearly two decades. One is Joan Didion’s “Insider Baseball”. Another is Gore Vidal’s “Norman Mailer’s Self-Advertisements”. There is also Edmund Wilson’s essay on ee cummings, and several by Dwight MacDonald. And there are two by Lester Bangs: “Astral Weeks” and “Thinking the Unthinkable About John Lennon”.

The latter was short, and written within hours of Lennon’s murder. It was wise and sharp and true. The shock of the moment didn’t bend his integrity; he didn’t surrender to sentimentality. But nor did he cynically milk the moment, and deliver pitiless contrarianism. There was vinegar and there was tenderness. What he wrote about was eulogising a past – and a person – that never existed, other than in our fantasies. The writing was beautifully balanced.

I can't mourn John Lennon. I didn't know the guy. But I do know that when all is said and done, that's all he was — a guy. The refusal of his fans to ever let him just be that was finally almost as lethal as his "assassin" (and please, let's have no more talk of this being a "political" killing, and don't call him a "rock 'n' roll martyr"). Did you watch the TV specials on Tuesday night? Did you see all those people standing in the street in front of the Dakota apartment where Lennon lived singing "Hey Jude"? What do you think the real —cynical, sneeringly sarcastic, witheringly witty and iconoclastic — John Lennon would have said about that?

John Lennon at his best despised cheap sentiment and had to learn the hard way that once you've made your mark on history those who can't will be so grateful they'll turn it into a cage for you. Those who choose to falsify their memories — to pine for a neverland 1960s that never really happened that way in the first place — insult the retroactive Eden they enshrine.

So in this time of gut-curdling sanctimonies about ultimate icons, I hope you will bear with my own pontifications long enough to let me say that the Beatles were certainly far more than a group of four talented musicians who might even have been the best of their generation. The Beatles were most of all a moment. But their generation was not the only generation in history, and to keep turning the gutted lantern of those dreams this way and that in hopes the flame will somehow flicker up again in the eighties is as futile a pursuit as trying to turn Lennon's lyrics into poetry. It is for that moment — not for John Lennon the man — that you are mourning, if you are mourning. Ultimately you are mourning for yourself.

Then there is his famous – I think I can call it “famous”? – essay on Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks. It opens like this:

Van Morrison's Astral Weeks was released ten years, almost to the day, before this was written. It was particularly important to me because the fall of 1968 was such a terrible time: I was a physical and mental wreck, nerves shredded and ghosts and spiders looming and squatting across the mind. My social contacts had dwindled to almost none; the presence of other people made me nervous and paranoid. I spent endless days and nights sunk in an armchair in my bedroom, reading magazines, watching TV, listening to records, staring into space. I had no idea how to improve the situation and probably wouldn't have done anything about it if I had.

It ventures out into touching interpretations of that strange and beautiful album – and yet the writing is plain, direct and humble. “You’re probably wondering when I'm going to get around to telling you about Astral Weeks,” he writes. “As a matter of fact, there's a whole lot of Astral Weeks I don't even want to tell you about. Both because whether you've heard it or not it wouldn't be fair for me to impose my interpretation of such lapidarily subjective imagery on you, and because in many cases I don’t really know what he’s talking about.”

I’ll say little more about it, other than that you should read it. But it still seems to me just about the perfect album review – in its close ear to the music itself, as well as the strange effects it has upon him. Leaning into the self’s reception of an album, you will always risk extreme self-indulgence and the estrangement of the reader, but somehow Bangs brings us in – illuminating his own depressive funk, as well as Morrison’s inscrutable mysticism.

*

Music writing is far less important than it was back then. No one is turning to underground ‘zines or street press or counter-culture glossies to figure out what album they should next buy with their fast-food cheque. The gatekeepers have long changed – as has the very idea of gatekeeping. I doubt that ever again we will have a famous rock critic.

And so these self-glorifying bad boys of the ‘70s – the Pioneers, if you will – have been forgotten, and if they haven’t, then regarded as laughable and misogynistic anachronisms. And that seems fair enough, to a point.

And so, what’s the point? Well, there’s precious little good music writing these days and, while I think this has always been true, I think there’s less folks willing to risk embarrassment to write the enduring stuff. And as contemptuous as I am of Kent and Meltzer (and many others), I would still caution against throwing out the historic man-child with the bathwater.

If Van Morrison could summon angels, then Lester Bangs could hear them.