“You always hear writers complain about the hellish difficulty of writing, but it’s a dishonest complaint… Having difficulty writing? Has it occurred to you that maybe you have nothing to write?” – Paul Theroux

“Back to writing for the first time in 6 months and why does it feel so hard, now? Why is writing a few words so exhausting. It’s just... it feels so foreign again, almost like a battle, you know? like I got rusty.” – representative lament from a random person on Twitter

*

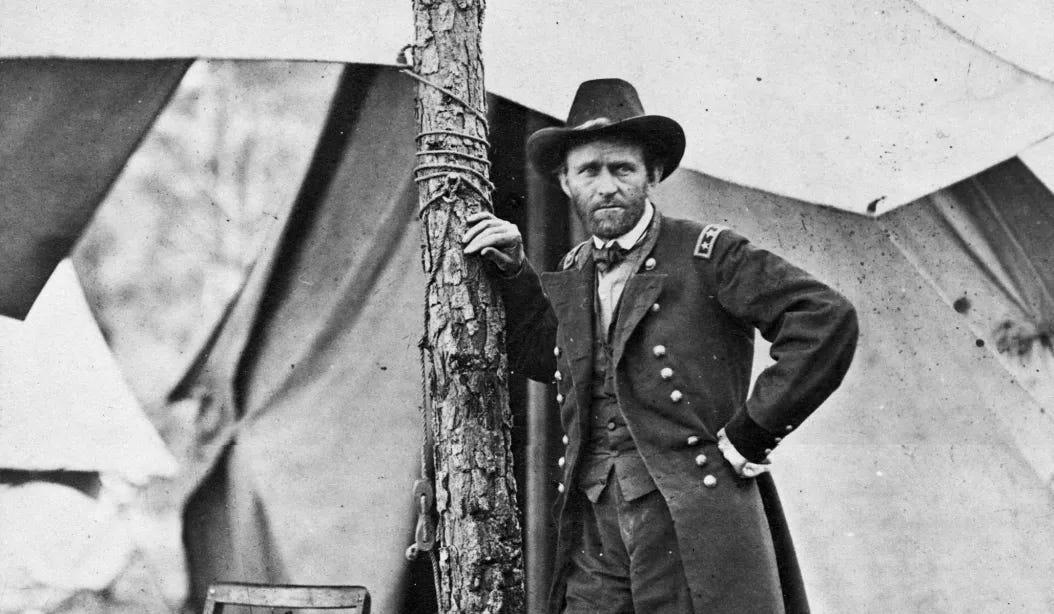

In his final summer, the former president sat shivering on his porch swaddled in blankets. On his lap lay a board, upon which were sheafs of paper, and around him were conifers and maple trees and beyond them the peaks of the Adirondacks.

Ulysses S. Grant was dying. In fact, within six weeks of moving to this cottage on Mount McGregor, in upstate New York, he will be dead from throat cancer. He can no longer eat solid foods and doctors inject him with brandy and swab his throat with morphine. His other medicine? Cocaine.

Grant was very weak by now, and had mostly lost his speech, but he would remain on that porch until the mosquitoes forced his retreat, committed to finishing his final testament and making his Hail Mary pass.

There were visitors, too. Curious or reverent strangers arrived in streams, alerted to both his location and morbid condition through newspapers. They would climb the hill upon which his cottage sat, and wave to him as he sat on the porch scribbling with his pencil.

It was the summer of 1885, and a little over a year before he was told that he would soon die. A little time before that, the financially hapless Grant had invested most of his savings in an early Ponzi scheme and was quickly made destitute.

Always reluctant to write his memoirs, his sudden destitution persuaded him. His death sentence then intensified his commitment. He would write them, and write them well, so that he could die having left his family something that might restore their security. He refused to die knowing that they were impoverished.

It was now an anxious race. His final transferable value – his recollections of the Civil War as its most honoured general – was something that he was unsure of having sufficient time, health or skill to record. Nor was he ever convinced of its commercial appeal.

But he continued. As he shivered, he wrote; and as he received injections of brandy, he received the enthusiastic passage of pilgrims. He was encouraged in all of this not only by his desire to ensure his family, but by the support of his friend Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain), who had pledged to both publish and publicise his book.

For as long as Grant could speak, he would receive Twain on the porch and the men would talk about the book and the war and how one might describe its bloody complexity precisely. “When I put my pen to the paper, I did not know the first word that I should make use of in writing the terms,” Grant would later say about sitting with Robert E. Lee to write the terms of surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia. “I only knew what was in my mind, and I wished to express it clearly, so that there could be no mistaking it.”

Civil War historian James M. McPherson says the same applied to Grant’s memoirs.

Abraham Lincoln had enjoyed great rapport with Grant, and the two communicated with letters and telegraphs of unusual lucidity. Both were gifted writers, but they were gifts sharpened by necessity: the communication of complex military movements through letter or telegraph could not abide any ambiguity.

Lincoln despised lazy writing, as he did the evasive and obtuse. He considered fuzzy writing to be the function of fuzzy thought. In a letter, one of Lincoln’s personal secretaries, John Hay, wrote of his boss’s gratitude for having found someone in his military – an engineer – who could write effectively:

“This is Herman Haupt, the railroad man at Alexandria. He has, as [Lincoln’s Secretary of the Treasury] Chase says, a Major General’s head on his shoulders. The President is particularly struck with the business-like character of his dispatch, telling in the fewest words the information most sought for, which contrasted strongly with the weak, whiney, vague and incorrect dispatches of the whilom General-in-Chief [George B. McClellan].”

In Garry Wills’ book Lincoln at Gettysburg, he writes: “Lincoln’s respect for General Grant came, in part, from the contrast between McClennan’s waffling and Grant’s firm grasp of the right words to use in explaining or arguing for a military operation. Lincoln sensed what Grant’s later publisher, Mark Twain, did, that the West Pointer who once taught mathematics was a master of expository prose.”

In little more than a year, Grant wrote a memoir of almost 300,000 words, at least half of them committed in deathly pain. The morphine helped not only to relieve that pain, but to soften the effects of the cocaine so that he might sleep. Grant had supreme will, but to complete his final task also required a diet of uppers and downers.

On his wicker chair, often swaddled in blankets, Grant pushed himself to complete the memoirs. Reporters camped before his property, anxious to witness – and then report upon – the death of the great general and ex-president. This had occurred in his family’s Manhattan brownstone too, the one they left for Mount McGregor. Grant’s biographer William S. McFeely wrote that one journalist boasted of seducing the servant of a nearby house, so that he might assume the special vantage of the home’s attic from which to better spy upon Grant’s residence.

There was a public death watch and there was intense suffering; there were mosquitoes and there were hiccups of confidence. There were blighted veins into which the brandy was punched; and there was the fear that the damn thing might not be finished before he was.

But don’t embrace too quickly the stoicism of Mr. Grant – he was both reclusive and desirous of public acclaim, and McFeely argues that there were other, more private options for his final retreat. In his last weeks, Grant did not object to the crowds but found pleasure in their attention.

Still, these were strange days for a strange man, and whilst dying he achieved his goal – a memoir of exceptional clarity completed just one week before he died. It begins: “My family is American, and has been for generations, in all its branches, direct and collateral”.

The memoirs were a phenomenon – one of the best-selling books of the 19th century. Helped by Mark Twain, who arranged Union veterans, dressed in their old uniforms, to sell the book door-to-door, the memoirs sold hundreds of thousands of copies in advance of its publication. Grant had achieved not only the insurance of his family, but his desire to write something precise and honest – a book that would be celebrated by Henry James, Gertrude Stein and Edmund Wilson.

The British critic Matthew Arnold, who had met Grant in 1877 and wrote that he was “dull and silent” would commend the memoirs for being “humane, simple, modest; from all restless self-consciousness and desire for display perfectly free” as he would also condescend Grant for a book written in “an English without charm and without high-breeding”.

This predictably enraged Grant’s great patron, Mark Twain, who said: “When we think of General Grant our pulses quicken and his grammar vanishes. We only remember that this is the simple soldier, who, all untaught of the silken phrase makers, linked words together with an art surpassing the art of the schools, and put into them a something which will still bring to American ears, as long as America shall last, the roll of his vanished drums and the tread of the marching hosts.”

And there it was: the presidential memoir that never describes his presidency; the memoir of a blood-soaked General who wrote with unusual charity about his old foes. A book made while dying, by an untutored drunk, that remains distinguished not merely by the circumstances of its creation, but the crystalline clarity of its sentences. Of his letters, Henry James wrote “The old American note sounds in them, the sense of the ‘hard’ life and the plain speech” and the same held for the memoirs.