The weird and violent humiliation of Mo Troper happened suddenly, in March last year, and per the natural inclination of vigilante justice, the online mob swelled quickly and deliriously. And it would almost kill him.

It was a Friday when the musician first learnt that something might be wrong. Troper was out jogging in his neighbourhood of Portland, Oregon, when he received a text message from a friend. It interrupted the Elvis Costello song he was playing, and so he stopped to read it. “Are you okay?” the text read.

Troper had no idea what it referred to. But he soon would.

*

I read Mo Troper before I heard him. An essay of his, published in some obscure corner of the internet, in which he ambitiously attempted to define his great passion – power pop – as well as explain his curious ambivalence to it.

I can’t remember how I found it. Certainly, I’d never heard of him before. But the guy could write, I thought, and his enthusiasm for the genre was obvious in his encyclopaedic knowledge of it.

But it was his ambivalence that really interested me. “My relationship to power pop is characterized by [an] ouroboros of sympathy and revulsion,” he wrote. “I admire it and detest it. I am consistently moved by it and also horribly embarrassed to have anything to do with it. To me, power pop is so much more than chiming guitars, heavy drums, and aching vocal harmonies – and simultaneously so much less.”

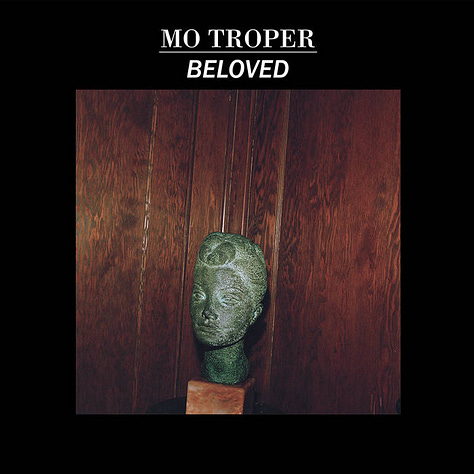

The author’s bio told me that he didn’t just philosophise about power pop, but that he wrote and performed the stuff. Curious, I found his albums. Immediately, I loved them. It turned out that Mo Troper wasn’t just an interesting philosopher of an unfashionable genre, but a superbly gifted maker of the stuff – and my favourite musical discovery of 2022.

Now 34, the singer-songwriter and producer lives in Portland, Oregon. He’s released seven albums in all, or eight if you include the Covid-project he made in his bedroom: a faithful, solo recreation of The Beatles’ Revolver.

Troper’s released a collection of Jon Brion covers, The Raspberries make him cry, and in his own music you can variously hear the influence of early Robert Pollard, Matthew Sweet, The Cars and Fountains of Wayne. Pitchfork favourably reviewed a few albums too, but for years Troper’s talents have been expressed in relative obscurity.

We first spoke in early 2023. He was unusually thoughtful. We talked about his ambivalence and painful self-awareness. In this context, he told me of a dream he’d had recently. In the dream, he plays a friend a new song of his – and his friend thinks that it sucks bad. “Well, I didn’t mean it,” dream Troper says defensively. “And that’s the problem,” his dream friend replies. “You never mean anything.”

The dream stung because its meaning wasn’t cryptic. For the man who’d written “The Only Living Goy in New York”, he wondered, after he’d woken, if he pre-empted failure with a schtick of ironic detachment. Was he too apologetic for his tastes? Too apologetic for desiring a career making such music?

As it was, such neurotic hang-ups would quickly seem insignificant. The thing that would threaten his career, his health and reputation would be found elsewhere. And so, from far away, my interest in Mo Troper was revived again for the worst reasons.

*

On that Friday in March last year, Troper would soon learn the significance of his friend’s text: his ex-partner, the musician Maya Stoner, with whom he’d broken up with two years previously, was alleging on social media that he’d been a “violent” and “serial abuser”. No evidence was given, though increasingly personal information was made public about him: his medications, therapies, sexual kinks and bipolar diagnosis.

Troper felt sick. But as sick as he felt, he couldn’t quite appreciate the gravity of the situation – not yet, anyway. It was like the very beginning of Covid, he told me, when the threat still felt fuzzy and indeterminate. But then you go to the grocery store and see that half the shelves are empty.

“It was a Friday, and I sent the head of the record label I was signed to – Lame-O – a text that was like, ‘Hey, this thing is happening. I don’t really know how crazy it’s going to get, but I just want to let you know,’” he says. “And he was like: ‘Shit, this is really bad timing. I’m about to get on a plane to Texas [for the SXSW festival], but let’s touch base on Monday.’

“So, I had these conversations with a lot of people along those lines, like, let’s sort of wait out the weekend and touch base on Monday. And then I think when Monday came around, those people had already made up their minds and there wasn’t really a dialogue – it was too late for that, you know? That was really disturbing. I mean, there’s a lot about it that was, and still is, really disturbing. To have people in my corner say, ‘this isn’t a big deal, we’ll wait this out’, and then to have their tenor change completely over the course of a weekend was really bizarre.”

*

On Sunday, March 17, Stoner posted that Troper was a “straight up sick in the head violent and depraved person.” On Monday, Troper’s manager, Luke Phillips, posted a series of tweets about his decision to “step away from being Mo’s manager,” and wrote that “I believe Maya. I hope everyone involved can take the steps to heal and grow from this, and I hope that those blindsided by these allegations like I was can find space to support each other through whatever they need going forward.”

Camp Trash, a Floridian indie band who had flown into Oregon to begin recording with Troper that very day, withdrew their association with him. Band member Keegan Bradford tweeted that “upon hearing Maya’s story, myself and the band have made the decision not to move forward with recording our album with Mo, and we hope Maya can find comfort and healing”.

Things were falling apart quickly. The next day, Lame-O Records dropped Troper. “In light of recent information, we will no longer be releasing Mo Troper’s album Svengali,” they wrote. “Refunds will be available at point of purchase. We are sending healing thoughts to Maya and victims of abuse everywhere.”

This was then reported by various music press – NME, Stereogum, Pitchfork, Brooklyn Vegan – some articles of which carried domestic violence hotline numbers. It had the effect of solidifying nonsense.

Despite his obscurity, Mo Troper became a trending topic on Twitter. A storm of savage hysteria was building. His public statement, flatly denying ever being abusive, seemed to mollify no one. “The transformation of my life happened over the course of a week,” he tells me.

The allegations bent his career, and nearly killed him. And they would all be recanted just months later.

*

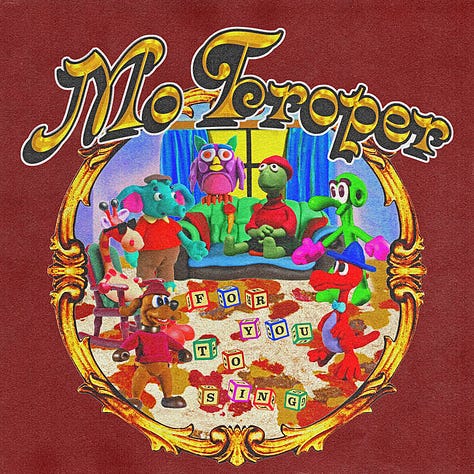

In March last year, Mo Troper was preparing to release Svengali – his seventh album and the one, he thought, that just might make him. But Svengali wasn’t coming out now.

On that Monday after South by Southwest, Troper spoke for an hour with Eric Osman, the manager of his record label. Troper says this was about the sum of dialogue with most of his representatives. “I think that they weren’t totally convinced [about the allegations],” Troper says. “I could start to sort of sense them starting to delude themselves – I could sense that they were searching for a justification.”

That the label had abandoned Svengali was noisily celebrated online. Troper was now perceived as a sex criminal and sick predator, and faced with the corresponding online abuse, he naturally closed his social media accounts. But the actions of an innocent man cruelly besieged can look much the same as a guilty one, and friends told him to reconsider. “I deleted my socials right away because I couldn’t deal with it,” Troper says. “And then everybody was like, ‘Oh, you know, it looks really bad that you deleted your socials’. Okay, well, I’ll reactivate them.”

He probably shouldn’t have, but when he did, he says he found proof of the hypocrisy that flourishes on social media. “There were people whose band’s Twitter accounts were publicly denouncing me, and then in private one of their members would be really sympathetic,” he says. “And instead of being like, ‘suck my balls’ or whatever – which now I realise would have been a reasonable response to that – I was like ‘Oh, it’s so good to hear from you. Thank you so much for checking in.’ I was just so desperate to maintain any connection.

“I think that my immediate response was sort of to – I don’t want to say ‘pander’ – but I think I tried to be as charitable as possible towards anyone that was willing to still talk to me, because I quickly went from being like ‘Shit, how can I salvage my career?’ to ‘How can I maintain some kind of support network?’”

A neutral observer would have seen the astonishing volume of abuse and his ex-partner’s vindictive airing of intimate details and winced. A prudent observer might also have wondered if this wasn’t all very strange and unsatisfactory as evidence, and if a grave and potentially dangerous injustice wasn’t being committed.

I write “strange and unsatisfactory” for good reason: in the hundreds of impulsively shared messages and filmed monologues by Maya Stoner, paranoia and erraticism were conspicuous qualities: “people are banding together to silence me”.

There were also gulfs between what was being alleged and what was offered as proof. Gossip was invoked as inviolable; indignation was expressed when evidence was asked for: “You don’t believe me because I’m an autistic sex worker and I’m indigenous and I’m a person of colour”.

Disordered thinking was attributed to Stoner’s autism, and the inconsistencies of her stories to trauma, while the word “evil” was used several times to describe Troper – and his dreams, song lyrics and press releases were all offered as “proof”. None of this seemed right, or healthy, even from a distance.

Naturally, a traumatised person may not present as strictly coherent – but in this specific and floridly bizarre case, there were sufficient grounds for pause amongst those who knew neither party and yet participated in the hysteria that drove Troper to hospital.

Upholding this public mania was the #MeToo creed “Believe All Women”, which is, or was, an extreme response to a very real problem – that is, decades of abuse victims whose allegations were dismissed or cruelly diminished. But the infinite credulity that “Believe All Women” demands is hardly practical, nor compatible with basic principles of law or journalism, even if it makes for a good badge.

To briefly venture a motherhood statement, the safety and credibility of alleged victims must be considered, but it’s impossible for the law’s presumption of innocence to operate simultaneously with the creed. Obviously.

But it’s a problem too complicated to consider. It’s much easier, as was the case with Mo Troper, to righteously dismiss anyone expressing neutrality, uneasy ambivalence or distaste for mob justice as being immoral enablers of rapists.

I suspect that those who most ardently invoke “Believe All Women” accept, but rarely say, that the inevitable collateral damage that follows from such radically inflexible credulity is entirely justified in the name of yanking the pendulum back. But if that’s the case, then say so: that you think injustice is inescapable but justified to correct for a greater injustice.

There have been some important scalps of genuine monsters: R. Kelly, Jeffrey Epstein and Harvey Weinstein, say. Each practiced the ritualised abuse of women, and enjoyed explicit or tacit support for it. But Mo Troper ain’t those men.

Mo Troper was collateral damage.

*

In June last year, Troper sued Stoner for defamation. Vindication – but not the reversal of serious damage to his health and reputation – would follow in October. That’s when the defamation case was privately settled, and Stoner retracted her myriad public allegations of abuse.

In an affidavit, she admitted that those allegations had “impacted [Mo] and his career”. There was also a statement:

“While there were some issues with our relationship and it was emotionally fraught for both of us at times, Mo was not abusive toward me as that term is legally defined. I will continue processing other aspects of our relationship in private. Troper and I have signed a mutual no-contact agreement, and I will not disparage him publicly again.”

When I asked Maya Stoner for comment, her response in full was this:

“Mr. Troper has already publicly stated almost a year ago: “We have resolved this matter and hope everyone will move forward from this situation.” I ask your publication to respect the wishes of both parties involved.”

It was not “almost a year ago” but only a few months, and the suggestion of some mutual agreement of discretion was misleading too: the other party, Mo Troper, was happily speaking to me.

Lame-O Records didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment, nor did they publicly respond when Stoner recanted her allegations last year. I suppose they’re just waiting it out.

*

In late March last year, Mo Troper admitted himself to a Portland hospital fearing that he might kill himself by overdose. He had briefly considered the prospects of his career, but was now simply considering his own physical survival. A few weeks later, his younger brother would post: “Sick to my stomach at what has happened… I have lost countless hours of sleep over this and so has my entire family. Not to mention the SEVERE amount of emotional turmoil, distress and anxiety it has put on my brother.”

For a long time, Troper was scared to leave the house. He does leave it now, but with a painful self-consciousness. The weird and slanderous campaign against him – magnified by countless strangers – has contaminated the world a little. One might favourably settle a defamation case, and have poisonous slanders formally retracted, but one can’t assume that others know. Or care. Others will move on, forget. But for Troper, the world will never quite be as it was.

“I remember that somebody posted about it on Reddit, and they were like ‘This has to be the worst music cancellation I have ever seen’,” Troper says. “And in some ways that’s really validating, because I’m in a state of paralysing anxiety and now I’m like: I guess I’m not overreacting, the bear really is chasing me.

“But at the same time, you want somebody to just tell you it’s going to be okay. The first time I hung out with somebody who had something similar happen to them, I realised how starved for it I was. Hearing that it would be okay. That time’s your friend. Because it’s such an isolating experience. And I think the only people who can do that are the people who have been through something like this and are still alive, frankly.”

*

One of the stranger elements of Troper’s public stoning was the use of his lyrics as evidence for his alleged wickedness. On social media, Stoner would often cite and feverishly interpret them – as if it were a “smoking gun” offered triumphantly by the prosecution. The public obligingly followed, applying bizarre literalism to Troper’s lyrics, in a manner either radically naïve or cynical.

Lyrics may be confessional of course, or they may not be – they may, in fact, be entirely fictional. They may incorporate exaggeration, imagination or irony. This hardly needs to be said, you’d think – and yet his lyrics were routinely cited by people as proof of Troper’s “evil”.

“Suddenly, this record that is just like a collection of love songs that sounds sort of like the Beatles, is like this concept album about being a serial abuser, or whatever the fuck people thought that it was,” Troper tells me.

“I think that there’s this misconception that all lyrical music is diaristic. And you look at a lot of artist bios now, there’s sort of this feigned vulnerability which I think is a lot of the time a marketing ploy. And I think that people just have this tendency to buy the narrative without question.”

This also applied to his former label. “[Eric Osman] really knew in intimate detail what these songs were about, and suddenly it seemed like he was incredulous towards all of that,” he says. “There’s a song on the record called ‘The Face of Kindness’, and he’s like, ‘Well, now I’m worried that anybody could misinterpret any of these songs, like, in ‘The Face of Kindness’, you say, ‘killing the face of kindness’. Like, what are people going to think about that? And suddenly I had to justify my art to this person who had really encouraged me to make art and to go as deep inside of myself as possible, you know? I was now interrogated about lyrics. It was absurd and insulting.”

Troper’s point here is that his label knew quite well the origins and intentions of his lyrics – they’d spoken at length about them before the storm came. But now they were concerned about the perception of them. Of zealots parsing the lyrics of an obscure power-pop artist for proof of his grave crimes.

Absurd and insulting is the very least that can be said about that.

*

In my experience, indie music scenes are possessed of great moral vanity – and yet this incident was distinguished by moral cowardice. I think of George Bernard Shaw when he said: “An Englishman thinks he is moral when he is only uncomfortable”.

Troper’s indie scene was uncomfortable. There was his immediate dumping, as there was a conspicuous (though not total) silence from those who knew him. People I attempted to speak to for this piece, who accept that Troper was subject to a serious injustice, are still wary of speaking publicly lest they receive blowback, for example: “you’re a disgusting piece of shit for supporting an abuser but all of Mo’s supporters have been disgusting pieces of shit so that’s not surprising”, as one social media poster put it.

There was also the weakness of the indie music press, who for a very long time now – here, and in America – have largely served to launder press releases and score free gig tickets. Stories aren’t written or verified, they’re simply shared from the publicist – and should the story be wrong, then one conveniently retreats into the hedge. As far as I know, no music writer who shared, or re-wrote defamatory press releases, has bothered to contemplate the story of Mo Troper or acknowledge their complicity in his public stoning.

So, here’s two difficult but very adult lessons: 1. That in the fashionable name of “courageous accountability”, injustice might be committed. And 2. That the music press is dead, has been for a long time, and that its sad remnants are upheld by the regurgitation of tribal pieties and press releases.

One friend of Troper’s, who asked to be left unnamed, told me: “I don’t think any of the outspoken people who were convinced Mo was an abuser learned anything from this. Maybe some of them did privately, but not in a way they would ever admit. Some of them have gone on to use Mo’s taking legal action against his accuser as further evidence of his abusive nature. There is essentially no way for Mo to truly win in this situation as the damage that was done was done immediately.”

*

Mo Troper eventually released Svengali independently. Pitchfork didn’t review it. Social media makes him sick now, and he can barely log on. You may then sensibly want to implore the guy to stay logged off, as I have, but when you’ve made an album you love and have had to release on your own, the poisoned waters of social media are still the ones you need to promote your work on.

What was once acutely painful for Troper was the understanding that nothing he said might help. A beastly image of him had been made, broadcast, and then ratified by the public abandonment of his own colleagues.

Mo Troper was a victim of false allegations, but also a cipher for thousands of strangers. He became a cultural voodoo doll. “I feel like one of the main takeaways is that there’s nothing you can do once you’re in that timeline,” he says. “Like, ‘Oh, if only I had addressed this in my statement’ or something – it’s like there really is only one outcome no matter what.”

He doesn’t know what will become of his career, if anything. But he’s still working: writing, producing. Some people have apologised to him, and he’s accepted those apologies. But the industry itself is stained for him. Filled with careerists who bend in the breeze and pretend their flexibility is moral courage.

In other words: they’re just fucking uncomfortable.

Great article, very considered and thought-provoking. And you introduced me to Mo Troper's music, extra thanks for that.

thank you for this Marty, really well done.