“Life, it seems, is not meaningless but, rather, so full of meaning that its meaning must be constantly murdered for the sake of cohesion and comprehension. For the sake of a story line.”

– Karoo

Before his death, Steve Tesich experienced something like a conversion: from optimistic American immigrant to furious jeremiah. The conversion was bitter, of course, a slow curdling of idealism that would produce fierce and morally dogmatic plays in a vein not unlike the late work of his hero, Tolstoy.

It would also produce a comic masterpiece, the posthumously published and perfectly neglected Karoo, a novel that even the endorsements of Arthur Miller and E.L. Doctorow could not save from obscurity.

*

Steve Tesich was born in the small Yugoslavian city of Užice, now part of Serbia, in 1942. The year before, his country was quickly conquered by, then divided among, several Axis powers. Tesich’s father, Radishe, was a professional soldier opposed to his country’s resistance force – the anti-fascist communist guerrillas led by Josip Tito. He vanished during the war and his family presumed him dead.

The young and fatherless Tesich was adored by his grieving mother, and he played among bomb-struck buildings that his imagination transformed into ancient ruins. An abandoned German truck became an aeroplane, and with his best friend Slobo they often commandeered it for daring reconnaissance flights. They played two roles and took turns assuming them: the pilot and the passenger forced to parachute from the plane when it’s hit by enemy fire.

He compulsively wrote short stories, many of them idealising his missing father, and he visited the city’s lone cinema, where a stream of Westerns fed his idealism of America. John Wayne was a fixture of his inner life, and Tarzan too, and so was Hollywood’s cosmology of an eternal struggle between light and dark, good and evil.

In 1980, when Tesich won an Oscar for best original screenplay – beating Woody Allen’s Manhattan, among others – he gave a short, sweetly sentimental speech describing how he half expected, when he first arrived in America as a teenager, to be collected by a friend of John Wayne’s and taken on horseback across the country’s endless frontier. He finished by saying: “After all these years of being here, I’m so grateful to be given an opportunity to send back a film, and to tell them that I find it very much like the place I’d seen originally: the good and the bad still fight it out; the good still tend to win in the end.”

*

Plot twist: his father wasn’t dead after all. Radishe resurfaced in England in 1955, a decade after the war, and his abandonment of his family, it turned out, was not that of the martyr but the scoundrel. By letter, he suggested to his family that they move to England, but eventually the United States was settled on for their reunion.

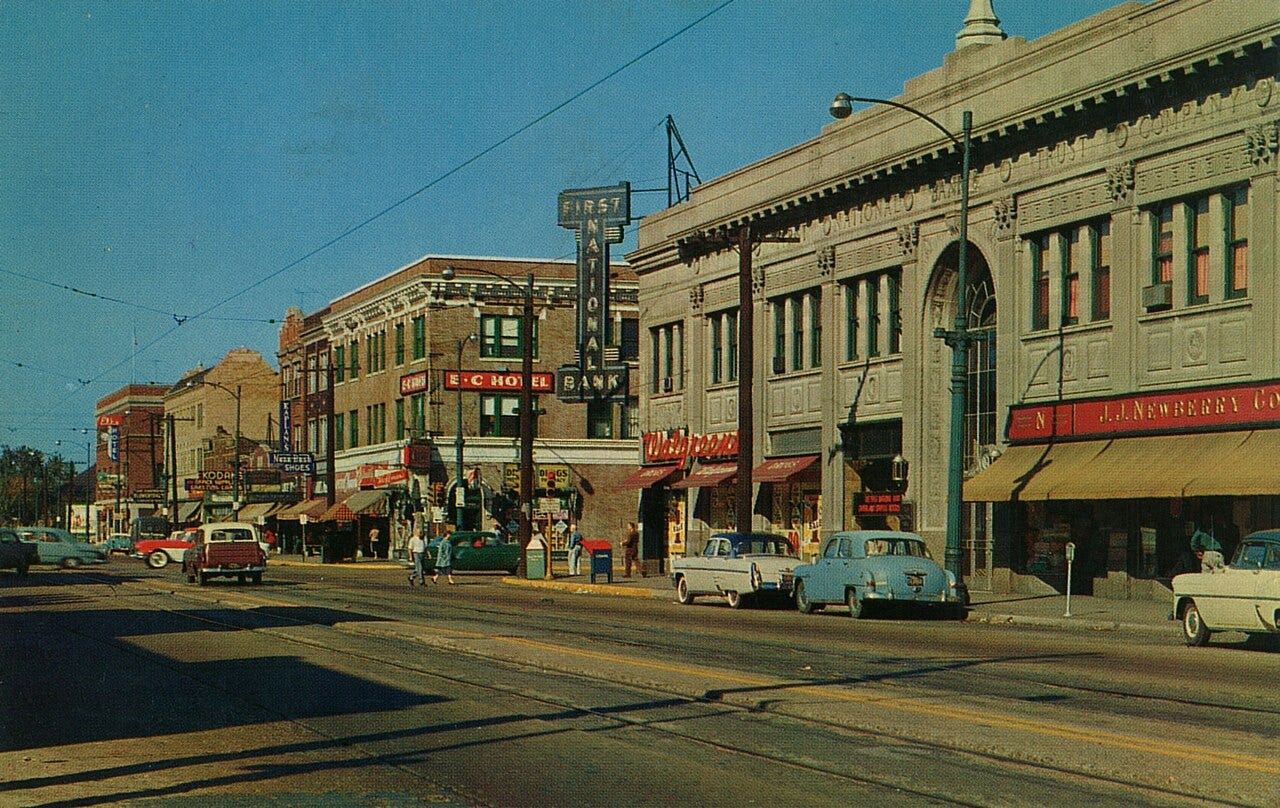

Radishe Tesich moved there first, to find employment and a home before the arrival of his long-estranged family. And so he did: he was hired as a machinist in a steel plant of East Chicago, Indiana. It was a heavily industrialised town, filled with factories, smokestacks and a permanent haze of pollution that transformed the dusk sky into a great blaze of orange and red.

The family was reunited there in 1957, and Steve Tesich was 14 when he first saw the country that he’d so often dreamt about. But neither his new home nor resurrected father resembled his dreams of them. The gritty steel town was a long way from windswept prairies, and the reality of his cold, embittered father was painfully incongruous too.

Decades later, Steve’s sister, Nadja, would say that their father was heavy with a frustrated sense of superiority – that he seethed with the sense that his life had gone wrong somehow, that he was an actor in some cheap play that he never wrote but was forced to appear in.

The profundity of having children that thought him dead for so long was not something he recognised, much less dealt with, and the adult recollections of his son and daughter were of a man who could never rise above his own resentments.

Just five years after the family’s reunion in America, Radishe Tesich was dead from a brain tumour. Not long before his own sudden death in 1996, Steve Tesich remembered his father and their reunion in an interview: “We thought he was dead, but he was, in fact, spending time wondering whether he wanted to have us together again. Then he thought it’d be nice, and so we all had some miserable years together, and then he died.”

*

The dreams of Steve Tesich recovered from their collision with reality, as he recovered from the death of his father. In one way, it was a reversion to the family’s previous configuration: the sole font of love and stability had always been their mother. Radishe’s children, when they were older, would come to think that their father never adapted to the primacy their mother had established in his absence.

Tesich learnt English quickly. He had a gift for its acquisition, and then its use, and he wrote often. He studied Russian literature at university, but came to think of himself as an artist, not a scholar. “I was a doctoral candidate in Russian literature,” he said in 1992. “Life was beautiful, secure, but I left all that. I jumped without knowing where I would land. If one is to be an artist, it’s for one’s whole life, whether you become amazingly successful or are a failure … If you want to be a writer, then you must be one your whole life. This is primary. If you consider changing professions, your writing won’t be as good as if you decided to devote your life to it. If you expect rewards, you are a goner.”

Tesich was 49 when he said this, and well into his conversion, and there’s something severe and monkish about his testimony to artistic commitment. That commitment was there 20 years previously too, but the expression of his art was different then.

In plays like Division Street (1980), he riffed upon the possibilities available in America, and the various conflicts of his heroes were often resolved sentimentally. Tesich was too smart not to complicate the American Dream in his fictions, nor fail to see its contradictions, but he essentially wrote from a place of grateful subscription to the idea that America was a healthy mess, a vital chaos in which dreamers could dream and immigrants might flourish.

In 1980, not long after he won an Oscar for his screenplay for Breaking Away, he told The New York Times: “I started looking at the incredible variety of American life, the nationalities, the people who would never be living next door to each other in any other nation, and somehow, they were getting along. It was such a unique feeling to see that kind of flexibility in an enormous country, and to watch it function. It got to me, and made me love the place very much.”

The next year, he would adapt John Irving’s novel The World According to Garp for a film starring Robin Williams, and appeared on The David Letterman Show to spruik it. I wonder if he then loved America more than his dead father and, if so, if anyone could possibly blame him?

Reunited with the unhappy and unloving Radishe in a blighted town in which he barely spoke a word of English, Tesich nonetheless accepted the promise of his new country and found distinction and artistic satisfaction there by using the language he didn’t know when he first arrived.

*

Fame, or something like it, came after the surprise success of Breaking Away (1979), a small-budget coming-of-age film, and now a niche classic, which borrowed heavily from Tesich’s life. The tropes are familiar: four working class boys struggle against their parents, their culture’s low expectations and their town’s privileged university students, who are so snidely contemptuous of the “townies”. In the film’s climax – a bicycle race that pits the townies against the cocky and presumably superior university team – the friends’ gumption prevails over the arrogance of their rivals.

The film was another love letter to his adopted country, but its authentic, sharply drawn sketches of the friends’ camaraderie, and the mutual bafflement between children and their parents, lifted the film above its sentimentality.

Not long after Breaking Away came 1981’s Four Friends. It was a bizarre mess, and understandably a critical and commercial failure that would haunt its once-revered director, Arthur Penn. Where Breaking Away held a steady gaze on its characters and their environment, Four Friends was an indulgent pinwheel of Major Themes – a study of America in the 1960s that collapsed beneath the weight of its promiscuous ambition.

But Four Friends interested me for the poisoned relationship of father and son, and their conscription to a mutually unwinnable war. Their relationship is marred by some generational and cultural bafflement, I suppose, but mostly by the father’s implacable bitterness.

In Four Friends, Tesich’s fictional counterpart, Danilo, passively suffers the violence and projected disappointments of his father. Even when his father belts him, hungry for a reaction, Danilo refuses to respond – which only further enrages his father.

Bitterly resigned to his own ineffectuality, the father still wants to inspire something – even if it’s the retaliatory violence of his own child. Danilo’s refusal to fight back just seems like more evidence of his own powerlessness. “I did get to know my father, but only from a distance,” Tesich once said. “He was a very unhappy man who just wasn’t living the kind of life he wanted to live.”

*

Something happened to Steve Tesich. Sometime in the late 1980s, towards the end of Reagan’s time in the White House, he became sick with disgust about his country. The man who once glowed with gratitude about his opportunities now resented an industry that bullied artists into producing “cheeseburgers” for a “uniculture”.

The man who, in 1980, told The New York Times that he wasn’t particularly political now couldn’t think of anything more important. The man who, in that same interview, said that his internal “tuning fork” was vibrating with his country’s resurgent idealism was now bitterly lamenting its apathy.

In a 1992 column for The Nation, Tesich’s despair was pronounced. The crimes of the Reagan government were worse than Nixon’s, he thought, but even worse was the public’s indifference to them. Nixon and his band were crooks, he said, but at least there were proportionate consequences: Tricky Dick’s resignation and a national sense of repulsion.

The disclosure of the Iran/Contra scandal in 1986 – in which the US government illegally trafficked weapons to Iran to help fund the anti-Sandinista guerrillas in Nicaragua – revealed a feverishly byzantine plot that was executed for years with pervasive dishonesty.

But for Tesich, the scandal was not met with proportionate consequences. And the main reason, he argued, was the American public’s distaste for more bad news. They could choose either truth or self-esteem, he wrote, and they’d chosen the latter – there was only so much accountability they could bear.

The American people, of whom he had once written hymns, were morally myopic: “We have lost faith and contact with our national myth. We are guided by expediency alone.”

It is hard to overstate the venom and despair contained in the pieces, interviews and copious, unpublished letters he compulsively sent to the editors of The New York Times (which have been independently collected online). They resemble the smug, conspiratorial contempt of the late political writing of Gore Vidal – a time when that great man of letters befriended and praised the Oklahoma bomber Timothy McVeigh.

Once a land of opportunity, America was now an open sewer: a land of murder, greed and apathy. The American people were estranged from their founding fathers and the best promises of their country’s conception. The estrangement, Tesich felt, was now systemic. “We don’t want [American children] to be well educated,” he said in 1992. “The last thing we want now is for an intellectually and spiritually vigorous generation to confront us with the question of what we have done to this country.”

What’s more, the sacred role of the artist had been thoroughly degraded. “This new era is a time of post-truth and post-art,” he said in the same interview. “Truth and art don’t exist anymore because man has been diminished. The artist today is a clown, an entertainer. I fight against this image, and I would rather die than become the same. Art is the only religion for me, because at least while I write I can believe in a truth. This is a hard time. It is when neither Tolstoy nor Dostoevsky are read. All the conditions exist, except the most important ones, for man to become a human being. However, man has been turned into something else.”

If there was a personal trigger for his conversion to raving jeremiah, I don’t know it. Tesich was enraged by what he described as the American demonisation of Serbia, though I’ve never found him to have made any reference to the genocidal nationalism that flourished under Slobodan Milošević.

Still, towards the end of his life, Tesich resembled a tortured, Tolstoyan priest. “[The] materialistic is 90 percent of life here,” he said of America four years before his death. “There are a very small number of people who see value in something else, and that is true not only in America. There was maybe never a balance. I don’t see if there is life anywhere that holds any deep feeling of moral ideas.”

I’m suspicious these days of writing that is so insistently rhetorical, and whose morality is professed so broadly, so loftily, as to resemble motherhood statements written on clouds. The late plays, essays and interviews of Steve Tesich strike me as articulate but ungrounded; misanthropic and unanalytical.

These are not grounds, I would have thought, for writing a literary masterpiece. And yet, in what he couldn’t know were his last days, that’s what he produced.

*

Saul Karoo is a Hollywood script doctor. Lacking any writing talent himself – or at least the will to develop it – he’s made good money re-writing scripts so they might conform to a studio’s commercial formulas. It’s work he does easily, bloodlessly and profitably.

Karoo’s “gift”, as the studios are fond of pretending, is finding “the spine of a story”: that is, re-writing interesting scripts into something viably generic. In other words: making cheeseburgers.

Karoo doesn’t suffer any delusions about his skill or importance. He knows he’s a hack, that he’s often paid to destroy work of rare originality, and is politely receptive to, but ultimately unmoved by, the flattery of his paymasters. Karoo’s villainy here isn’t that he’s captive to his own delusions: it’s that he’s become acutely morally lazy. He’s an alcoholic, chain-smoking nihilist that can’t even revel in his own nihilism – it’s not an enjoyable pose, but merely the function of a severe spiritual resignation that he’s helpless to reverse.

Saul Karoo is also a monster. An interesting monster in that he knows he’s a monster, and a bleakly funny one in that it’s often his passivity that’s the cause of so much pain. Karoo might be described as a long, hyper-articulate monologue of self-hatred, which might sound unappealing if it wasn’t so sharp and funny.

Karoo can’t enjoy his money, family or work – nor summon the effort to recover his enjoyment. He is repulsed by intimacy and can’t bring himself to spend time alone with his adopted son, who’s suffering from his father’s neglect.

The book opens at an opulent Manhattan house party in 1991, where its revellers try to impress each other with their pronunciation of “Nicolae Ceaușescu”, and Karoo tries to avoid his teenage son whom he knows will want to come home with him. “It had nothing to do with love. I loved Billy, but was absolutely incapable of loving him in private where it was just the two of us. That was another disease I had. I didn’t know what exactly to call it. Evasion of privacy. Evasion at all cost of privacy of any kind. With anyone.”

Later that evening, as Karoo finds his alibi for ghosting his son, he confesses to the reader: “I had habits of my own and one of them was to get overly sentimental about Billy prior to hurting him.”

Saul Karoo is a man without faith or conviction. A man who, like water, finds the quickest path and the lowest point. He’s emotionally estranged from everything, including himself, and the memory of his younger self is a strange abstraction, amusing in its faintly recalled idealism. Karoo would prefer to not be a monster of decadent amorality, but he just can’t find the grounds or motivation to correct it.

And then: an idea. A plot. A real-life screenplay for his own redemption, and his son’s recovery of faith in him. A plot that will require his destroying a director’s masterpiece, but a destruction justified by its helping forge a new family, a new self-conception, a new future… I’ll say no more about Karoo’s plan, other than it resembles the feverishness and complicated duplicity of the Iran/Contra affair.

And it ends badly.

*

Karoo is one of the funniest books I’ve ever read, as it is one of the most honest and bleak. It’s very funny until it isn’t, and its later scene where Karoo visits his mother is an exquisite rendering of loneliness. Tesich had spent his life thinking and writing about his relationship with his parents, and it found its most profound expression in Karoo.

There’s little redemption in Karoo, only delayed and bungled attempts at it, and one of the most piercingly honest descriptions of the gulf between parents and their children can be found here. After a lifetime of indifference and perfunctory communication, his relationship with his mother is denuded of feeling – when they meet, which is rare, they merely observe rote rituals of hospitality.

But now, in his widowed mother’s kitchen, and when the two have lost so much, Karoo falls to his knees and weeps and begs forgiveness for all of the love he’s withheld from her.

And she’s repulsed. Over many years, mother and son have made a long and loveless groove, and she’s too old now to accept the needle skipping. “Something real is creeping toward her. The first real moment between herself and her son is heading directly toward her. He is looking up at her. Her child. Her son. This old man, pleading with her. And she pleads right back at him, like some helpless old woman confronted by a mugger. She pleads with him to abandon his assault. Let us not have something real now, she pleads with him with her eyes. I’m an old woman. A widow. I haven’t got much longer to live. Please, spare me this moment.”

Too much time has passed. They’ve played their roles for too long. Empty roles, yes, but comfortably entrenched ones. The mess of confession is too awkward, and their loneliness is irrevocable, even as Karoo kneels in weepy submission to his mother and his guilt. “Our getting together again never really worked for him,” Tesich later said of his father. “Too much time had passed.”

*

Karoo should not have happened. A mad jeremiah rarely makes a good novelist, much less a successfully comedic one. But Steve Tesich did it. Embittered and self-righteous, Tesich wrote his novel as a scorned lover – an immigrant whose idealism had been unforgivably betrayed.

While suffering from his own disgust, Tesich somehow found a scalpel. A mallet or sledgehammer are usually the instruments found by an artist in such circumstances.

The precision of his sentences, and the sharpness of his jokes, testify to a rare control of his own bile. And while I accept E.L. Doctorow’s obvious proposal, recorded in his introduction to the book – that “the existence of a man like Karoo implicates the culture he speaks from, a culture of inauthenticity, roaring self-interest, and spiritual bankruptcy” – the book’s power for me was found not in its implications of a corrupted American culture, but in its intimate recording of a man’s lazy estrangement from himself and those he professes to love.

In Saul Karoo, Tesich wrote one of the greatest tragic-comic characters I’ve ever met. In his creation, nothing feels smudged, dodged or politely avoided. Nor does the creeping bleakness feel contrived. The late and revelatory anal bleeding is earnt. Karoo’s funny because it’s so fucking honest.

And then, in July 1996, just weeks after he finished writing it, Steve Tesich died of a heart attack. He was 53 and on a Canadian vacation with his family – his wife and eight-year-old daughter.

The exoticism of a posthumous release did little for the novel’s reception. There were perfunctory reviews, short and dim, as there was an oddly hostile review in The Washington Post in which the writer seemed to take personally the ugliness of Saul Karoo and the cynicism of its dead writer. “This is a cautionary tale, although Tesich may not have meant it as that, a cautionary tale for writers and artists,” Carolyn See wrote. “Be careful! Even if you have the stamina and inspiration and faith to write something magical, that stamina and inspiration and faith might fail. Unhappiness, equivocation and bad art might follow, and you might not be able to do a damn thing about it.”

See went on: “On the other hand, Breaking Away still remains with us, beautiful and untaintable, evidence of the real Steve Tesich, before life got to him.”

It’s not clear that Carolyn See realised that she was reviewing the work of a dead man, nor is it obvious what authority she possessed to declare what constituted the “real” Steve Tesich.

But dead he was, and almost 30 years later I won’t tell you that the real Steve Tesich can be found in Karoo – only that a weird talent was expressed and then ignored, and it shouldn’t have been.

What a wonderful piece of writing! Seriously good. I'm ordering Karoo now. Thank you for the introduction.

I'm ordering Karoo now.