Flower, don’t dig so deep so you don’t go anywhere/

Flower, don’t dig so deep you get in over your head.

— “Twilight Creeps”, Crooked Fingers

Self-imposed ground rules for the playlist:

To encourage variety, no artist could be included twice. Arguably there are some breaches of this, as when one artist covers another, or when one appears as a guest on another’s track. Or when I’ve included the New Pornographers and the solo work of its members, or conveniently treated Magnolia Electric Co. and Songs: Ohia as two separate artists. I’ve also allowed the 2015 live recording of Notwist’s “One with the Freaks” (2002) because their arrangement for its performance is so much better than the album version’s. Naturally, I’m fine with all of this.

Regarding omissions: Fatlip, Simian, Daft Punk, Camera Obscura, Vic Chesnutt, The Streets, The Decemberists, The Minders and David Bowie were all once included and then, alas, denied. I also couldn’t find space for the great Teenage Fanclub, but we all know that their best work was made in the decade previous.

Jim O’Rourke’s “Get a Room” from 2001’s Insignificance would certainly have been in there, but the man’s work is largely, and pointedly, kept from Spotify. The same goes for Kevin Shields’ original work for the Lost in Translation soundtrack (2003).

This is, of course, not my attempt to list the best songs of the decade — merely my favourites. Nothing more or less. And before I get to it, some loose & highly personal thoughts about that decade in music…

The Strokes & The O.C.: Indie Goes Mainstream

In early pieces here, I wrote about the popularisation of indie rock via glamorous teen soap The O.C. Phantom Planet provided its theme song, while love for Death Cab for Cutie provided one of its handsome leads with an affectation meant to suggest, I suppose, his kooky soulfulness.

As for The Strokes, I’ve argued that they were perhaps the last band to be celebrated according to their position within a once-popular schema for imagining the production of music: that is, the long push/pull between “real artists” and their whorish corporate marionettes.

As I wrote a few years ago:

The internet has vastly diminished the influence of music tastemakers in print and radio and, relatedly, I think it’s also diminished the grip of the idea that “true” music is constantly besieged by corporatisation, creating an endless but fruitful struggle that obliges artists to reinvent and reassert themselves against the periodic triumphs of mediocre “sellouts”. In other words, “true artists” have to rescue themselves from their own success. Thus, the popularity of Nirvana birthed insipid wannabes like Bush, Creed and Nickelback, and now fresh saviours were needed to restore order.

The Strokes were a significant band in the early Noughties, but I’d argue that their reception was just as significant. It was, I think, the last time that a major band was celebrated as rock’s holy defibrillators. Such celebration presumed 1. The existence of a sacred form of rock; 2. That its sacredness was determined by a largely intuited (and sometimes mysteriously defined) sense of authenticity; and 3. That this sacredness would be protected by the discernment of a few.

That’s gone now, I think.

Lush, fussy & dull “Chamber Pop”

To me, the Noughties are at least partially defined by the preponderance of “chamber pop” groups, many of whose names seemed to be derived, incongruously, from wild animals. Grizzly Bear and Fleet Foxes were two. Midlake, Band of Horses and Department of Eagles were others.

In my circles, these bands seemed ubiquitous in the Noughties. They also largely left me cold. Today, I can’t bear them. This is mere personal taste, and I don’t want to pretend that it’s anything else, but the ultra-polished “chamber pop” of these years now seems unbearably precious to me. If sloppy chords and fuzzy pedals could obscure a lack of talent, then so too could fancy schools and weeks in production substitute for melodic genius or electricity.

Here were a cluster of bands that cool white-collars played at dinner parties or first dates to suggest their sophistication.

OutKast Wrote the Perfect Song

It’s 2003 and a group of us are leaving a bar called Three Alleys, named for its location at the delta of three laneways in the back streets of Itaewon, Seoul. Outside we’re sinisterly met by three American GIs, all of them young and bored and determined to provoke at least one of us into some violent entertainment.

Evidently, they’d been lingering in the dark for a while — waiting for someone dumb enough to respond to their provocations. That night, that someone was me. From memory, they tried to bait the men of our group into confrontation by insulting the women – but I’m unclear on the specifics of their insults. What I do remember is that I lingered to exchange insults with these goons, and when I turned around my group had vanished around a corner or two.

War-starved and acne-scarred, Uncle Sam’s troops were waiting for a threshold to be crossed: some act or statement of mine that would justify my beating. And, though it was exceptionally strange, I gave it to them. As they yelled insults and encouragement to prove my manhood, I took to calling them pathetic Slim Shady wannabes. I’ve no idea why I said what I said next, but it was this: “You should listen to the first George Harrison record, you motherfuckers.”

I suppose I thought they were in need of some musical education, and that All Things Must Pass might invite some tenderness into their souls, but it was the “motherfucker” that at last provided their trigger for bashing me.

As they ran furiously towards me, I remember thinking: Stay on your feet. I didn’t. I couldn’t. I threw one ineffectual punch, then dodged another. Then I was thrown against the wall of the alley, cracked my head, and fell to the ground. I remember thinking: You’ve not stayed on your fucking feet.

Now on the ground, I assumed a protective pose as the boots arrived. And then: almost immediate salvation. From the darkness of the laneway, a Korean policeman arrived while blowing a whistle and waving a luminescent traffic baton. These GI fuckers were not only beating a civilian, but were doing so after curfew — and they ran. I stood and breathlessly thanked the copper, who spoke as much English as I spoke Korean. And that was that. He let me go.

To the next bar I went, where the group I’d been detached from were wondering where I was. As I was explaining my thwarted bashing, and the lucky survival of my organs, Outkast’s “Hey Ya” came on.

I stopped. What the fuck was this? It was clear within 30 seconds that this song was special, as it was obvious to me that we all should immediately dance. In that same bar for the next few months I’d hear the song every time I went in, and obviously so did the whole world.

I remember reading an issue of Time magazine around then that interviewed a range of eminent figures about their reaction to the song: one of them was Colin Powell. Only months earlier, he’d presented bogus evidence before the United Nations to help justify an unjustifiable war — one that some Korean kids I knew would be conscripted to. Everyone, it seemed, had a view on that song.

Modest Mouse Become Immodestly Massive

Their first two albums sounded to me like the inspired noise of trailer-park dirt-bags — singularly weird and raw and unlikely to ever fill stadiums. Their lyrical subject was often the bad vibes of large spaces, and they wrote albums that could soundtrack road-trips taken by paranoid misfits.

By their third album, 2000’s The Moon and Antarctica, there was already the suspicion the group had “sold out” — that their rawness had been commercially polished, their singular weirdness tamed. I couldn’t quite hear that tameness, to be honest, and nowhere near as loud as I heard the anxieties of their fans.

Album number four, Good News for People Who Love Bad News, became a mega-seller. Its production was cleaner, its atmosphere less doom-heavy, and in “Float On” they offered something I don’t think they’d offered before: an anthem.

But the distinctive tics of their singer Isaac Brock were retained, and so too their sense of seriousness. Good News… sounded like a very good band now 15 years into their existence and not so much trying new things as just writing commensurately with their mellowing.

As a fan, you can ache for their past rawness — but it’s not something you can, or should, affect as a band. Good News… was recognisably Modest Mouse, but it was also a subtle departure, and one that made them quite famous. A friend of mine was made despondent by either the success of Modest Mouse, or their subtly shifting sounds, though he denies both to me every time I bring it up.

It was a fine album, though I wouldn’t listen to many more of theirs after it.

Oasis Sucked, Then Croaked

It was in Paris, 2009, that the animosity between the Gallagher brothers finally killed the group. It was at least a decade overdue. 1997’s Be Here Now was desperate and coke-blown, but still proved more interesting than almost anything that followed it. This is something I’ve written on at length before, so I’ll keep this short: they released two wonderful albums, and an early treasure of B-sides. But their laddish charisma and brazen riff-theft couldn’t survive their musical limitations and they entered into a long passage of self-parody, despite the introduction of new band members and songwriters.

Anyway: musically, culturally, Oasis meant little in the Noughties and their death wasn’t much mourned — but enough time has since passed that the glories of their early years, and the ‘90s generally, can be revived and will underwrite their reunion later this year.

What’s Forgotten

Well, most things. That’s the way of it. But there’s one album from the decade I still love, and I think was obscured by it running hard against trends. It was 2003’s Guitar Romantic by the Exploding Hearts, a perfect refraction of ‘70s punk/power pop. Green Day had grown up on the same influences — the Buzzcocks, Undertones, Stiff Little Fingers — but were now older men making “rock operas”. The Exploding Hearts were still kids, and their influences still joyously untrained. It was the only album they made, though: three of the band’s four were killed when their van overturned on a highway on the way home from a gig that same year.

And Ramesh Srivastava — as Voxtrot — released a near perfect EP, Raised By Wolves, and his next EP Mothers, Sisters, Daughters & Wives was damn good too. But that first one? It lands as hard today as it did when I first heard it almost 20 years ago.

Post-Rock Becomes a Cult

Mogwai had released two albums in the ‘90s, and their influence was considerable amongst the young musicians I knew in Perth. The Glaswegians then wrote long, often entirely instrumental epics with guitars — songs made memorable for their patient, gentle beginnings and their almost obscenely noisy climaxes. Mogwai made distinctive songs — nay, atmospheres — without lyrics but a commitment to finding the most tender and brutal expressions of their instruments within the same song.

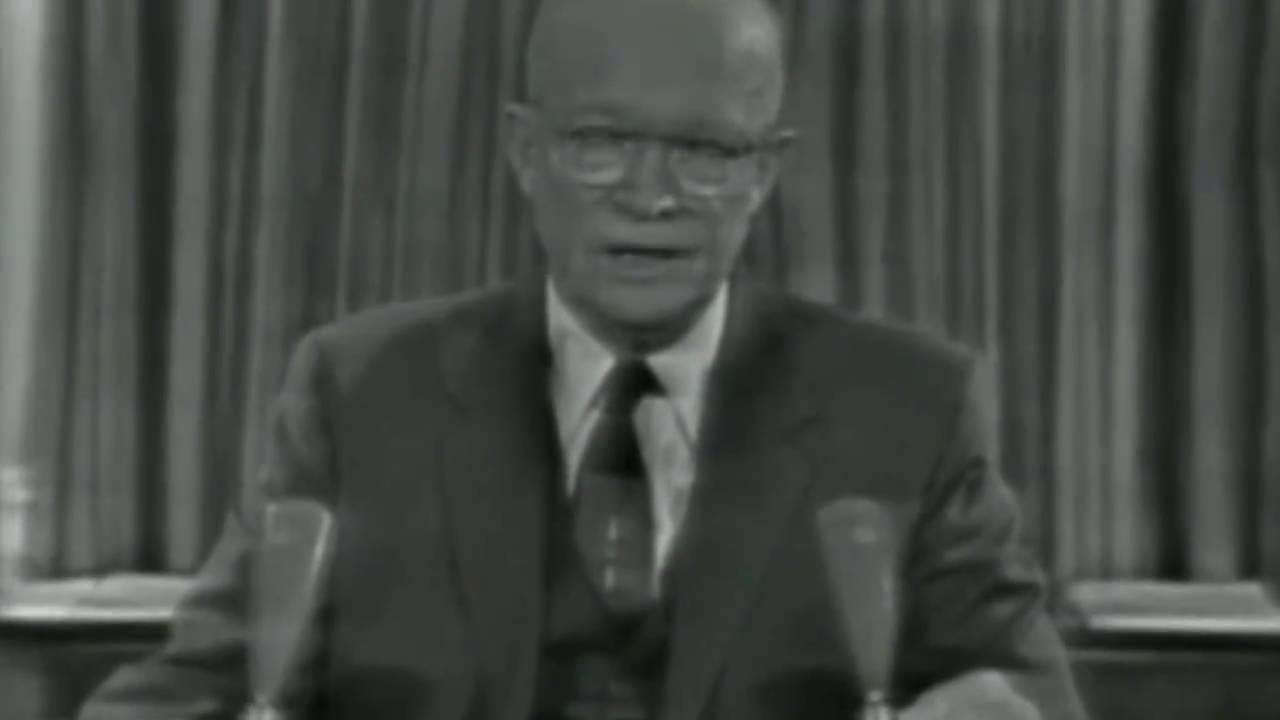

Then came Explosions in the Sky and God Speed You Black Emperor! A genre was born, and one that many folks I knew were enchanted with and wanted to emulate. I remember a gig many years ago, in a basement in Freo, where one band played their quiet/loud/quiet songs against a projected backdrop of Dwight Eisenhower making his farewell speech from the White House: the one in which he warns of the “military-industrial complex”.

Maybe it was good. But what was intended here was an atmosphere. And for a time, those I knew who were serious about music were very committed to the ambience and specific grammar of post-rock. To making a sound that was both fashionable but also suggested great seriousness.

It was a sound that could be done well or done poorly, but the odds of the latter — of making noise that sunk into pretentious murk — was high.

There Were Some Amazing & Singular Albums Which I Think Hold Up Very Well Today

To wit: Broken Social Scene’s You Forgot it in People. I’m still unsure how to describe this album, but some perfect chemistry was found in making it. From its soft, gently droning introduction to its crash of several guitars in track two, I don’t know many albums that so successfully mix styles. The album’s ambition is enormous and chameleonic and it all works.

My interest in the group becomes patchy after this. It doesn’t matter. They still released some damn fine songs, and it’s enough that they made this.

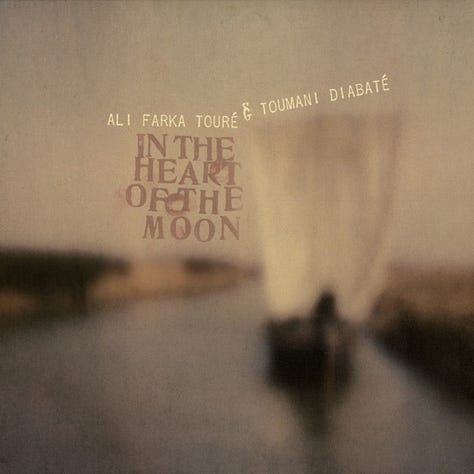

The Avalanches Released a Masterpiece

Early in 2000, as a kid hack on the student ‘paper, I received a CD. It was unclothed — no art work, just a disc in a clear case from Universal Music Australia. I brought it home, played it for my housemates and my God almighty. None of us could know it would become a classic, but our love was instant.

We were sitting on the stairs of our condemned “mansion” and enjoying the cheap rent that followed from our giant home’s decrepitude and terminal deadline: the whole place would be demolished soon. Before it was, about nine months later, this album would provide one of its soundtracks — something we listened to before we went out, and then again hours later when we came back home.

The album was a genius of collage — an imaginative, soulful mosaic assembled from the thousands of shards found by obsessive crate-diggers. 16 years would pass until they released their second album.

When the right writer finds the right subject, it is always a wonderful thing. Lovely stuff.